We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

In 2012, we were inundated: new artists, new labels, new microgenres, new ideas. A lot of these artists and labels were dropping releases so quickly (some weekly, some monthly) we could barely comprehend what was happening, let alone listen to them all, while journalists were scrambling to find new names for what was going on (doomstep, vaporwave, djent, hipster house, drill, etc.). It reached a point where there was an almost instinctual tendency to bracket any one-click genre creation as a temporary historical perversion: wait it out long enough, and the movement will either die or lose its cultural currency. Add the bottomless wealth of SoundCloud streams, Bandcamp uploads, DatPiff mixtapes, and Mediafire links, as well as the slipstream methodology of our most prolific reptilian artists, and it began to appear like music, over time, has been and will become increasingly fragmented.

But to understand music as being fragmented is to assume that there is something to be fragmented in the first place. Music for the past century has been best understood on the levels of syncretism, hybridization, and bottom-up subacculturation. Rather than fragmenting, the very conception of what music is, or what it can do, is simply expanding, reconstituting, and reinvigorating which notes can be played (Aaron Dilloway), which songs can be sampled (Daughn Gibson), which symbols can be recontextualized (情報デスクVIRTUAL), which genres can be reimagined (Sun Araw & M. Geddes Gengras Meet The Congos), which rhythms can be danced to (DJ Rashad/Traxman), which bodily noises can be aestheticized (Scott Walker). It’s at once about adapting and preserving, revising and recycling, progressing and regressing, evolving and devolving. All of these artists on this list contribute not only to an expansion of music’s identity and reach, but also an expansion of taste, where the perceptual foregrounding by artists like Dean Blunt can exist alongside the modernist narratives of Swans, where the pitch-black beats of Raime can complement the ecstatic harmonies of Grimes, where taste is reinforced by Frank Ocean but problematized by INTERNET CLUB, where the conceptual cinema of Kendrick Lamar can offer respite from the heretofore unimagined disgust of Scott Walker, where the untreated voice can be heard as alien (Laurel Halo) and the treated one as embodied (Holly Herndon, Farrah Abraham).

To defragment, then, would be to revert to classicism, to essentialism, to tired notions of authenticity. It would also be impossible. Humanism ain’t what it used to be, such that the default position of the modern listener is decidedly posthuman, favoring disunity, telepresence, and multiple perspectives: We don’t pronounce artist names; we copy-paste into search boxes. We don’t recall the past; we retrieve information. We don’t listen to notes; we identify symbols. We don’t create genres; we recognize patterns. Sure, it can be scary to see consensus drifting away, to watch values you once held so close morph into something once again foreign, to witness how quickly technology can be rendered obsolete by the faster dominating the slower, to observe not only the degradation of the environment, but now also the degradation of our collective imagination and memory. But what opens up is the possibility of adopting emerging, fluid identities, of inserting yourself in varied contexts politically or aesthetically. It’s a process of potentially becoming and embodying both nothing in particular and everything altogether, with the quaint idea that the next breakthrough in consciousness/justice/whatever may very well just be deceptively dormant, eager to find expression at just the right moment.

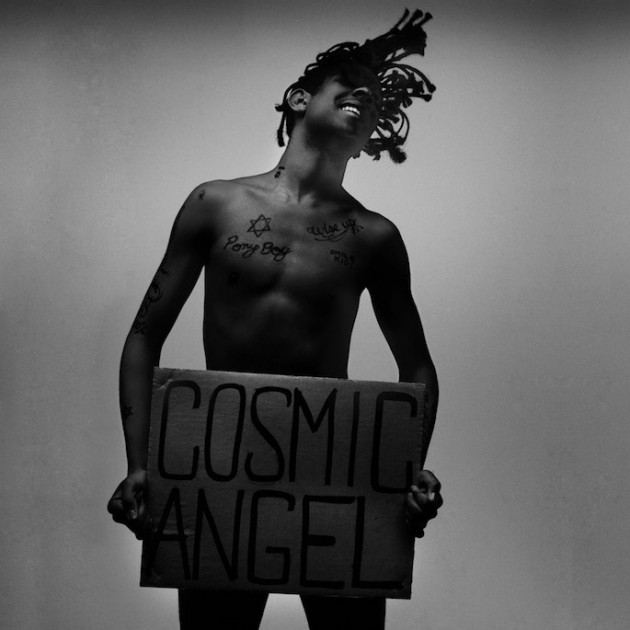

50. Mykki Blanco

Cosmic Angel: The Illuminati Prince/ss

[UNO NYC]

Immersed in a sea of dolphins, octopuses, and underwater aesthetics, 2012 got pretty wavvy, while Mykki Blanco’s Cosmic Angel: Illuminati Prince/ss mixtape employed the dank beats of post-corporeal producers like Nightfeelings and Matrixxman to submerge our ears deeper into the abyss with a distinctly gritty mutation. The Gobby-produced “Riot,” for example, flaunted a particularly subaquatic production quality with its filtered, low-end beat. Alternatively, on “YungRhymeAssassin,” Blanco affirmed her fluid lyricism over a distinctly buoyant production by trap darlings Flosstradamus, comprising the genre’s signature airy snares and handclaps. In spite of its title, Cosmic Angel was far from angelic; Blanco rhymed about sinful scenarios including promiscuous sexual behaviour with DJs (“Fucking the DJ”), and her fierce tone, notable on the Benmar-produced “Kingpinning (Ice Cold),” remained frozen solid, bearing the entirety of the album. Moreover, Blanco’s hard militant demeanor, exemplified by the gabber-infused track “Virginia Beach” and visible in the video for “Haze.Boogie.Life” (which featured Blanco brandishing a baseball bat), clashed with a softer exterior of girlish attire, subverting any princessly presuppositions.

49. Raime

Quarter Turns Over a Living Line

[Blackest Ever Black]

No city knows how to commodify its past into neatly packaged scenes like London does. Or how to brood over something embedded in its cultural guts. But to make the connection between jungle and goth as Raime did is more curious than knowing. After plowing through Detroit techno, bass, and jungle, the pair of DJs who call themselves Raime found meaning at the bottom of the pile with 80s industrial and goth. Quarter Turns Over a Living Line was a rich, textured debut, made by men in their 30s willing to bang sheets of metal under bridges like oafish art students to get a first-pressed field recording basis to their sound. Their label Blackest Ever Black has pledged to resist the increasingly rarified and bland cycles of dance music by encouraging DJs like Raime to use real drums and cellos. But there is a reference less tribally pure than goth/industrial, which goes unacknowledged in Raime’s debut: the dark dinner party vibe of 90s Bristol trip-hop. Quarter Turns Over a Living Line was a smog-tinted record for their own city, to stand in good company with the urban synthesis of their gloomy DJ forebears. Although Raime favored a more gritty perspective over the aerial view of laptop composers, they still made a curiously urbane record: blacker in tone than in spirit.

48. Belbury Poly

The Belbury Tales

[Ghost Box]

It’s 1973. Halfway through the filming of The Wicker Man, a freak incident with a combine harvester leaves composer Paul Giovanni dead, forcing director Robin Hardy to look elsewhere for a soundtrack. Hardy searches high and low for a replacement. Delia Derbyshire, electronic music pioneer extraordinaire, has just left the BBC to score horror films, and a desperate Hardy engages her on a whim, when, out of nowhere, his quixotic begging-letter to Fairport Convention bears fruit in the form of an unlooked-for affirmative. What to do but allow them to work together and see what emerges from this fecund, pagan cauldron? This, obviously, is an alternate history, one that could have produced The Belbury Tales. But content aside, alternate history itself is very much what the Ghost Box label, and founder Jim Jupp’s Belbury Poly project, is all about: a hauntological retro-futurism that draws on Astley-esque pastoral and BBC Keynesianism. Elsie Wright and Frances Griffin produced photographs of the fairies at the bottom of their garden in Cottingley; similarly, The Belbury Tales is the unreliable quarter-plate record of the time that Jupp saw something nasty in the woodshed.

47. INTERNET CLUB

VANISHING VISION

[Self-Released]

This year, among the more enigmatic corners of the internet, a handful of artists took a late-2000s trend toward revitalizing the written-off sounds of nascent commercial digital instrumentation to its extreme. Visually identified by an esoteric take on early digital 3D animation and loosely grouped as vaporwave, these musicians often foregrounded the incidental, architectonic music of the boardroom, airport, or plaza, demanding a confrontation with the musical inheritance of global capitalism, about which the music had an eerily ambivalent relationship. INTERNET CLUB’s VANISHING VISION stood out among those who would make miracles from muzak. On a conceptual level, as James Parker put it in his review, VANISHING VISION was “a dramatic demonstration of the fact that the music/muzak distinction has always been unstable at a time when it’s less stable than ever before.” Its source material was, while never loose, vaguely human, from the wonky and inscrutable mallet percussion of “Zones” to the hyperactive R&B guitar in “Pacific” to the downright beautiful depth of “Ever be Real.” But music built on reframing, altering, and appropriating those pieces of the musical past — often to an acute degree — appears to be a project that bears only limited fruits. If so, VANISHING VISION helped point the way out before INTERNET CLUB, along with other key practitioners of the genre, vanished themselves.

46. Converge

All We Love We Leave Behind

[Epitaph]

In his review of Converge’s eighth studio album, Birkut wrote, “All We Love We Leave Behind entices kinetic release in every possible way.” Truer words have never been written: the latest offering from the Salem punk innovators just may have been their most explosive. With the marked absence of the digital effects featured heavily in the band’s last several albums, the hooks hit with twice as much force and none of the filters. With Jacob Bannon’s feral shriek now doubly piercing, the already-intricate riffs revealed even more complexity. Best of all, the aggression neither relented nor slipped into the redundancy that’s an all-too-common problem among their peers. The frenzied, almost drunken grindcore of “Tender Abuse” seamlessly flowed into sludgier cuts like “Sadness Comes Home” and “A Glacial Pace,” and on the title track, they sounded groovy. Ultimately, All We Love We Leave Behind proved to be the kind of record to throw caution to the wind, flip the bird, and take immense risks in nearly every aspect of its construction. And that fearlessness paid off: we’d be hard pressed to name many 2012 records more exhilarating than this one.

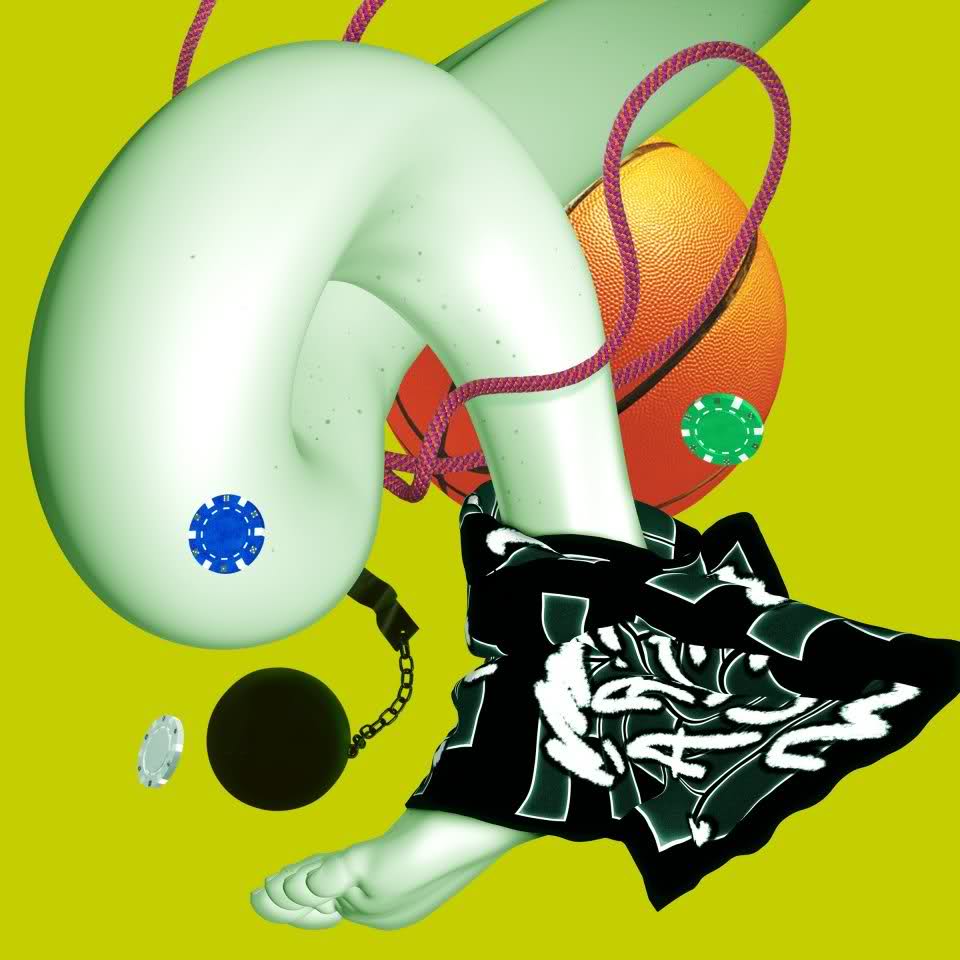

45. Arca

Stretch 2

[UNO NYC]

Familiar elements of exercise, recreation, gambling, and incarceration float in a pea-soup-green void on the cover of Arca’s Stretch 2. These ordinary objects are obscured by a humorous yet unnerving gray elastic leg that’s twisted, tweaked, and stretched in unnatural and impossible directions. This is much like the music that played beyond this fascinating and uneasy exterior of Arca’s second release of 2012. The clean-cut, delectable textures and rhythms that Arca produced here were — by themselves — masterful achievements of beat-oriented electronic music, but it was the vocals that made Arca’s work infinitely intriguing. Sure, they recalled the familiar elements of gangsta rap and modern hip-hop that we all know and love, but they were so heavily manipulated that the resulting inflections and phrasings became something else altogether: not a voice, not a synthesizer, but a horrifying, untameable monster. In fact, by the last two tracks, the monster had retreated back to its dark, dank dwelling, and Arca’s brilliant instrumental work slowly dragged us back down to Earth, where things just didn’t sound as cool.

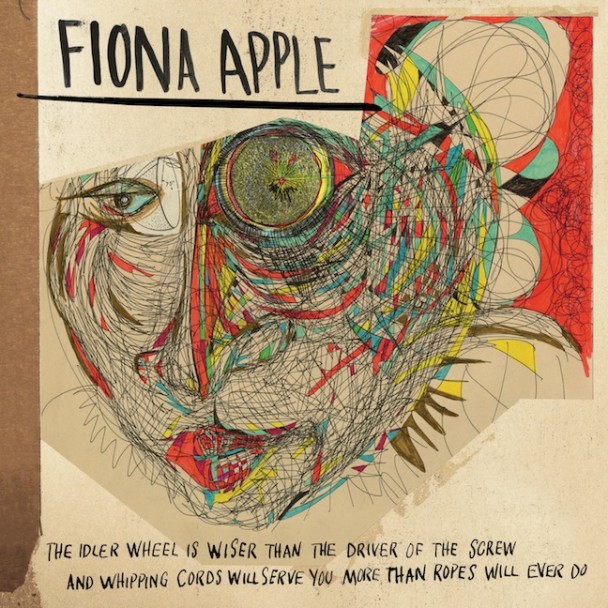

44. Fiona Apple

The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do

[Epic]

Describing music as “emotional” is among the laziest and most short-sighted critical tools. Although you can typically suss out which emotions are being lauded, it suggests that certain emotions are more genuine, more real than others. So prepare to call me a hack when I admit I constantly reach for “emotional” when describing Fiona Apple’s The Idler Wheel. Apple’s fourth album was charged with something, but what? It was sad, but rarely depressing. It was angry, but rarely bitter. Even its moments of deep uncertainty sounded bathed in a soothing tranquility. “Every single night’s a fight with my brain,” she sang on the record’s opening, but she sounded full-throated and celebratory. Yet even then, the record never approached the time-honored, arguably cynical tradition of juxtaposing happy music with sad lyrics. Sure, The Idler Wheel was an exquisite piece of work, a show of masterfully economic songcraft that found Apple succeeding as she took her most uncomfortable leaps. More importantly, though, it was proof that she had reached a level where she can bypass typical modes of expression via song, obliterating artifice for something decidedly hers.

43. Killer Mike

R.A.P. Music

[Williams Street]

Looking back, I can’t help but think that any vote against the Killer Mike/El-P ticket in the 2012 election was a wasted one. We need these guys in charge, people. On the one hand, you had Mike on the mic, brain and brawn, a trained, tried-and-true veteran with an intimidating (read: confident and, yes, charming/disarming) Southern drawl that managed unparalleled agility despite its gravity. On the other, we have El-P ‘s production matching Mike’s unstoppable aggression with laser beams of synth and pulverizing blasts of bass, pushing Mike’s triumphs of tradition headfirst into the unforeseeable future of hip-hop, a sentiment no more apparent than on the album’s title track. On R.A.P. Music, it all came together into something more than just a great listen. Mike’s record was downright inspiring: a rapper unafraid to show his seams/weaknesses and capitalize on them to better himself, a guy who could both spin a gripping (or hilarious) yarn when he wanted and, of course, wax the freshest of politics (see: “Reagan”). This meant crumpling the whole damn system like a ball of trash into the palm of his hand. So then, America, the question becomes this: Do we get a redo, or what?

42. Death Grips

No Love Deep Web

[Self-Released]

The Deep Web is a void, a cesspool. It is the vacuum in which truth and reality is consumed and held captive — the truth of the real, of humanity’s brutal essence. The Deep Web “others” us by casting an image that we don’t want to accept. When the first thing you see is a violently erect penis, you can only imagine what the music will sound like. And it was abrasive, hyperreal, and strangely intimate. MC Ride’s delivery was raw and hoarse, exhausted from the hard-fought battle. For Death Grips, hell is other people, and the Deep Web connected those people and then made them an entity. In comparison, Exmilitary and The Money Store were just small-scale battles, the first movement. No Love Deep Web introduced the war. The void was swallowing us up, and Death Grips were the keepers of the void.

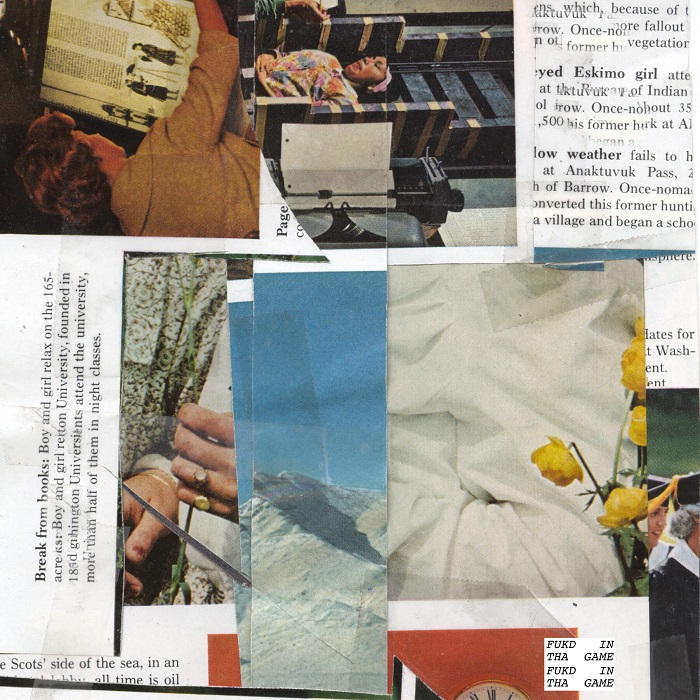

41. Heat Wave

Fukd In Tha Game

[Heat Rave]

In his quest to sample the entire internet, Alex Gray has tossed releases out like they’re wearisome sandbags weighing him down. Each mixtape was thrown haphazardly overboard and reached us as a chewy mulch of noise and relentlessly choppy rhythms. They all bore the sound of a man eager to get rid of his past before diving headfirst into a new project (DJ/PURPLE/IMAGE) — Gray is desperate, perhaps obsessed, with avoiding stasis. Yet rather than sounding like carelessness, Gray sculpted moments of arresting beauty from his dizzying array of samples. What was so entrancing about Fukd In Tha Game was its impenetrability — I doubt even Gray knew what was intentional and what was merely the result of random knob-twiddling/cursor-jerking at 3 AM. Thus, nothing sounded forced or contrived, yet Gray somehow staged a fascinating musical journey. We were casually led through bizarre experimentalism (“Smoke Rings”), chopped ‘n’ screwed R&B (“Party Time”), and poignant refrains (“Dem Boyz”) as if it were no biggie. Of course, there was no shortage of artists reappropriating the past, but Gray fucked with nostalgia in such a unique, bizarre, and precarious way that his creative stamp would be readily apparent on any musical debris he decided to grace with his presence.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series