We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

The mixtape was born in the clubs and block parties of 1970s New York City. Immortalizing Grandmaster Flash, DJ Kool Herc, and Afrika Bambaataa before the record industry ever realized that scratching wasn’t just something its sweaty execs did to their armpits, it compiled the best of these luminaries’ sets into condensed chunks that intermingled a hi-octane b-boying soundtrack with made-to-order namechecks. At the time, these recordings were a mirror to the scenes and the culture they sprouted from, with the extended length of their jams devised expressly to accommodate the breakdancing face-offs that went down at parties and the bountiful shout-outs reflecting the community and solidarity that threaded the dancefloors of the Bronx and Harlem.

But even if these naïve documents could be deemed the first-ever hip-hop albums, the earliest material evidence of a subculture finding its voice and unbridling its once-suppressed creativity, something happened over the course of the four decades between then and now to prune the florescence they represented. Like so much that emerges as a salutary blast against commercialized staleness, rap became a victim of its own success, the sprawling 14 and a half minutes of “Rapper’s Delight” (1979) and the still no-less epic 7 minutes of “The Message” (1982) — its first crossover hits — initiating a chain of profiteering and standardization that eventually resulted in hip-hop being swallowed by the culture industry and then shoehorned into a barely negotiable format, where even hallowed anthems like “It’s Tricky,” “Straight Outta Compton,” “Bring Da Ruckus,” “8 Steps to Perfection,” and “New Slaves” all partook of leaner, poppier 3- to 4-minute run-times, and where so many albums were reduced to mere repositories for formulaic singles.

This is where rap in 2014 comes in, because even though it remains a major cash cow for so many admirably greased middlemen, the march of the internet means that, in this year more than any other, these middlemen are being thwarted by something of a counter-movement. Not only is the commercial viability of the hip-hop album and single still being eroded by the ability to download albums before they’re even released, but it’s also being harassed by the ever-metastasizing glut of bedroom MCs, all of whom take advantage of internet technologies and distribution services like DatPiff, LiveMixtapes, SoundCloud, and Bandcamp to drown out traditional “career” rappers and DJs in a flood of competitors willing to do the same shit, only better and for free. This year, we’ve enjoyed peerless free-to-download records from the likes of Lil Herb, iLoveMakonnen, Lil B, Tink, Rich Gang, Father, Ethereal, Soopah Eype, Issa Gold, AK, Mick Jenkins, Migos, Rome Fortune, Rozewood, Death Grips, Ty Dolla $ign, Sicko Mobb, and many, many more, even from more “career” rappers like Future, Chief Keef, Curren$y, 2 Chainz, Wiz Khalifa, Cam’ron, and Mac Miller, all of whom had a tremendous impact on rap in 2014.

In view of such releases, it will be the argument of this retrospective that their breadth and quality leave us in a world where it’s becoming increasingly difficult for the more “legitimate” album to justify its own distinction and priority.

The Blurring Distinction Between the Album and the Mixtape

Travi$ Scott

Travi$ Scott

Here we arrive at a development unique to our present era, of which 2014 is only the latest expression: the dichotomy between the album and the mixtape is being blurred to the point where the distinction is becoming dramatically less tenable. Because we now live in a time when the gloried album is being downloaded and disseminated for virtually nothing anyway, and because we also live in a time when the scope and substance of the long-gratis mixtape competes with that of commercially released long-players, the difference between the one and the other seems to increasingly be mostly a matter of language. Or if not, at least mostly a matter of cultural positioning, in the sense that the hard-headed rap aficionado who wants to exhibit their underground credentials would describe, say, Travi$ Scott’s Days Before Rodeo from August as a “mixtape,” whereas those who want to align themselves with the greater status and gravitas that comes with being part of the commercialized mainstream (such as Travi$ Scott himself) might be tempted to label it as an “album.”

Of course, there is the rejoinder that the album is sold, and that it has to obtain clearance for any sample it might use. In contrast, the likes of Lil B and Jon Connor can appropriate Meredith Brooks’s “Bitch” and Kanye West’s “New Slaves” with impunity. However, aside from the fact that this minor legal distinction is indiscernible from an aesthetic/musical point of view, it’s further threatened by the waning profits to be extracted from copyright-cleared rap albums in the age of YouTube, Spotify, and cheap broadband connections. To take the worst-case scenario, such profits could dwindle to nothing, stripping labels of all and any rationale for paying off copyright holders and releasing albums as legally compliant consumer goods.

Some might find this line of reasoning a little disconcerting, since it would imply the eventual disappearance of the hip-hop album and by extension perhaps the very essence of hip-hop itself. So many of us identify rap with its canon of seminal albums — It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Paul’s Boutique, Enter the Wu-Tang, Illmatic, Aquemini — that it’s troubling to imagine an era in which budding musicians are deprived of a revenue stream to fund their artistic development. Yet perhaps the eclipse of the hip-hop album will be less an existential threat to the genre than a return to its roots, at least insofar as control over the resulting output will revert to musicians and the cultures that spawned them, slipping out of the clutches of record labels and their parent corporations.

It Takes a Music Industry Worth Millions of Dollars to Hold Us Back

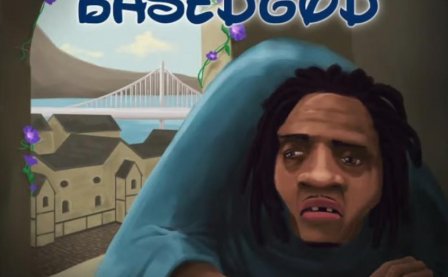

Cover art for Chief Keef’s still-unreleased “Bang 3” mixtape/album

Cover art for Chief Keef’s still-unreleased “Bang 3” mixtape/album

This line of argument is corroborated by the experiences of several high-profile figures who’ve suffered at the hands of the majors this year. In March, ScHoolboy Q shared the regrets he had surrounding the release of February’s Oxymoron on a major label, citing the the compulsion to promote singles and albums as a distraction from the creative process. There’s also the story of Chief Keef, whose Bang 3 was first changed from an almost-released mixtape to an “album,” and then repeatedly delayed this year by Interscope, with the label initially complaining that he was hemorrhaging too much free music too quickly. But in October, he was dropped from Interscope, which freed him to release the Back From The Dead 2 tape around a week after parting ways with his former stable (and many more since then). Even regardless of whether or not Back From The Dead 2 is a musical advance over 2012’s Finally Rich LP (which it is), its speedy, unilateral release stands as testament to the increased artistic autonomy the label-free mixtape permits.

And further evidence that MCs, DJs, and producers are already less constrained by commercial pressures and more able to express themselves however they want can be heard in the year’s best releases, with the unashamed heart-on-sleeve sentimentality of the iLoveMakonnen EP, the cartoonish hypersexuality of the Ultimate Bitch Mixtape, the unbound melodicism of Winter’s Diary 2, and the skittering mania of niggas on the moon all testifying to a liberated increase in self-expression and creative freedom. What’s more, the absence of label or corporate involvement in these offerings is more faithful to hip-hop’s origins and wider social meaning, since from its very beginning, the genre has been the music of outcasts, rebels, and outlaws, not that of millionaires or the executives and salesmen who ply them with fat contracts. The very idea that rap — once primarily the mouthpiece of the disenfranchised and disaffected — should ever have operated under the auspices of the rich and the powerful was an absurdity, a contradiction in terms, so it’s only fitting that in 2014 a significant proportion of the genre’s big players are doing their thing without outside interference.

It’s about time, too, because for far too long that interference had been diluting the distinction between tapes and albums for the worse. Initially, there’d been a tangible difference between the one medium and the other, with the mixtape of the 1970s emerging as what was essentially a direct recording of DJ sets and with the album later materializing as a collection of songs written and recorded in relative isolation from the social lifeblood of hip-hop cities and towns. For example, before Grandmaster Flash had released The Message, his 1982 debut LP with the Furious Five, he’d been charging $1 per minute of audio for compilations of his live performances for almost a decade. And much the same applies to Afrika Bambaataa, Grand Wizzard Theodore, DJ Hollywood, DJ Pete Jones, and almost every other major DJ to gain prominence in the 1970s, all of whom proved they were pivotal fixtures in hip-hop culture before they ever inscribed themselves on vinyl or compact disc.

More about: 2 Chainz, AK, Archibald Slim, Cam'ron, Chief Keef, Curren$y, Death Grips, Ethereal, Father, Future, ILoveMakonnen, Issa Gold, Lil B, Lil Herb, Mac Miller, Mick Jenkins, Migos, Rich Gang, Rome Fortune, Rozewood, Sicko Mobb, Soopah Eype, Tink, Ty Dolla $ign, Wiz Khalifa

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series