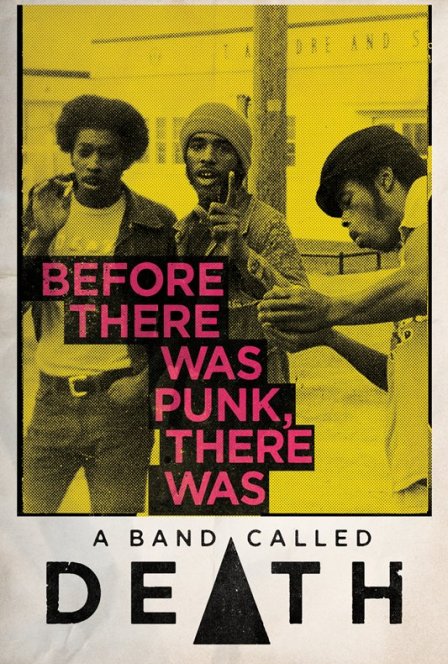

With A Band Called Death, directors Mark Christopher Covino and Jeff Howlett found a fairly incredible intersection of a few very rare and very desirable narrative qualities. Primarily, Death was an almost entirely unheard of band from Detroit that cut one album in 1974 and barely sold any copies. Death was also comprised of three wildly talented, self-taught teenaged African American brothers who embarked on an entirely new musical path. To top it all off, Death’s music was also unequivocally baller, embodying many of the same sonic identifiers that would find their culmination in the punk movement a couple years later. In the realm of music docs, you usually get a combination of one or two of those variables, but hardly ever all three (Searching for Sugarman is the only other example I can think of).

With such a wealth of attractive material at their hands, the only real danger Covino and Howlett faced was in taking it easy and banking that a built-in fan base of weird music aficionados would flock to their film regardless of how much effort they put into making it. To be fair, Death’s music alone is a good enough reason to see this documentary, as raw and emotional and unbelievably rhythmically tight as it is. However, not content to merely secure the rights for these great tracks, get a couple old punkers from Detroit to tell us how great the tracks are, and call it a day, the filmmakers captured a wealth of emotionally compelling interviews with the two surviving brothers of Death’s original lineup. Brothers Bobby and Dannis Hackney are initially giddy and surprised by how much young people are into the music they recorded in Detroit in the early 70s and are full of anecdotes about their zany brother David, who led the band in weird new directions while pissing off all their neighbors who couldn’t abide by more distorted versions of Who songs played by kids they thought should still be digging on Motown. In the midst of these joyful, electric recollections, the brothers begin to touch on what it was that led to their band’s demise and the failure to get anything started together afterwards, largely owing to David’s obstinance and almost religious devotion to the concept behind their admittedly awesome original band.

Throughout the duration of the film, the sense of loss these two brothers feel slowly becomes devastating and palpable, the two recounting their brother’s stubbornness and steady descent into substance abuse and alcoholism. We’re allowed to see them at their most vulnerable, helplessly watching the gradual demise of their older brother as he held so tightly to the original vision of a band that hadn’t played in decades. One of the sole reasons Death’s album For All The World To See never found adequate distribution hinged on David’s intractable position concerning their name. Shopping the record around to various distros, Death always heard the same thing: label owners telling them how much they loved the album and how many units they could move if only they’d changed the name of their band. In hindsight, it’s definitely a great thing they didn’t, and their penchant for using solid triangles in a lot of their band artwork will definitely give them traction with a lot of the kinds of people who might’ve used to write for Altered Zones (too soon?).

Obviously benefiting from a wealth of decent source material and the lucid recollections of emotionally attuned subjects, Covino and Howlett have made an undeniably engrossing documentary. This portrait of youthful experimentation is a joy to watch for many reasons, but the one that struck me the hardest was that these young guys weren’t really rebelling against anything. Rather, they were doing exactly what they thought was worth doing without much undue concern towards outside actors, which has always been more fascinating than young people who feel put upon by society and decide to thrash as a direct response to it.