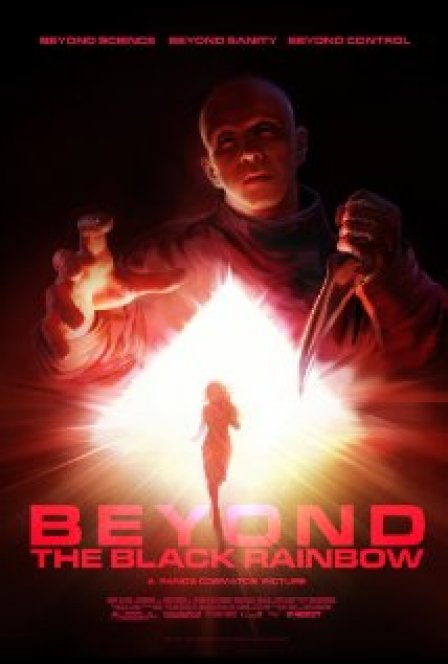

VHS fetishism occupies a peculiar space in cinema. It’s a part of the arch-camp that defines the style of the filmmakers in the Troma set, but it also maintains a confused relationship with the self-awareness that’s such a defining trait of camp. Videophiles find themselves enamored with both the shoestring aesthetics and the unabashed earnestness of filmmakers from Ed Wood to Ti West. Panos Cosmatos’ Beyond the Black Rainbow is a film heavily in thrall to the nascent VHS cult, drawing deeply from a tradition of marginalized genre and distorted aesthetic.

Story occupies only a fraction of Cosmatos’s project, while the fragments of Black Rainbow’s plot that are comprehensible tend to bleakness. There is a laboratory where an evil doctor works. According to the infomercial that opens the film, a researcher has discovered a means for generating happiness in subjects who enroll at the facility. As the film continues, it becomes clear the lab is occupied by only one patient, one doctor, and one assistant. Another doctor, Arboria — the founder and namesake of the facility — lies sedated and dying a few floors above. The patient, Elena (Eva Allan), suffers from an unimaginable psychic distress that comes accompanied by an unruly telekinesis. The doctor, Barry Nyle (Michael Rogers), practices a horrifying brand of psychotherapy; he is able to control the intensity of Elena’s pain with the turn of a knob. The assistant exists mostly because the second act needs a mutilated body. This is pretty much all the narrative Cosmatos gives the viewer; motivation isn’t discussed or addressed. The facility and its characters exist entirely so that Cosmatos can exercise his staggeringly impressive visual imagination.

The simplest visual analogue for Cosmatos’s designs would be Kubrick in 2001, but the intensity of color and contrast, the severity of objects and rituals, and the juxtapositions of horrific and vulnerable are all products of the director’s originality. He heaps image after image upon the viewer, paired with a score that alternates between ominous drone and the sort of techno that dominated darker film montages in the 80s. Unfortunately, Cosmatos is so enamored with creating his twisted psychedelia that he’s unable to communicate his ideas; rather than have style serve as text, the film instead ends up an incoherent series of images that haunt only up until they start to bore. Everything moves obnoxiously slowly; there is little dialogue, but when people speak they do so only in the same sluggish, exhausting cadence. Dr. Nyle is insane and has been for a long time; he’s reached a moment where he wants to both sexually overpower and physically destroy his patient, the near-paralytic young girl over whom his control is total. The source of Nyles’s insanity is unknown, as is Elena’s origin, and the film’s unwillingness to bend its aesthetic enough to let the viewer develop a relationship with any character makes it hard to care what happens to either protagonist. Given the film’s conclusion — a short chase scene; some lazy, random deaths; a faux-sinister and overserious final image — it’s not hard to imagine that Cosmatos doesn’t care what happens to his characters, either. They exist only so he can have a laboratory for his aesthetic.

Genre films often leave the critical apparatus bereft of anything to say; what that apparatus goes in search of, genre films dismiss out of hand (and vice versa). Writing, characterization, catharsis, and thematics are an afterthought for filmmakers like Panos Cosmatos. Instead, he obsesses over color and texture; meditating on the construction of his slickly constructed labyrinth and the violent choreography of his villain’s aggression holds more appeal for him than crafting an accessible narrative for his audience. Which is fine, sometimes: Beyond the Black Rainbow has one extended music break that makes it obvious how brilliant Cosmatos would be directing music videos. Unfortunately, these images would never be enough to sustain a committed viewer for two hours, unless that viewer was the sort of devoted genre acolyte for whom whole festivals and online communities exist. For the rest of us, Black Rainbow will remain frustratingly out of reach, an object only enjoyable as mute ornament, not as significant filmmaking.