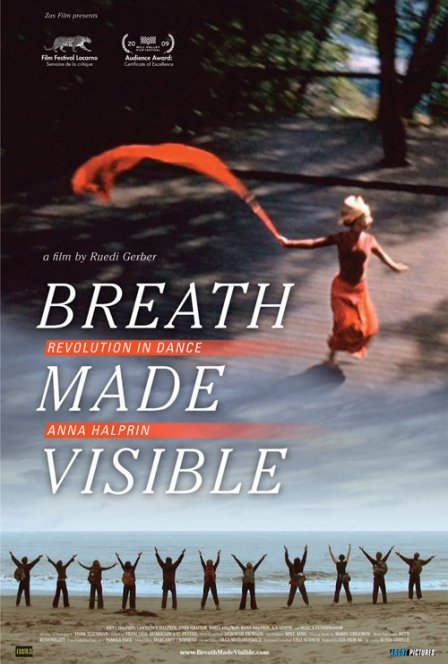

From the first moment the octogenarian modern dance luminary Anna Halprin appears on screen in Breath Made Visible, her presence electrifies. It’s the way she moves, a lone figure in a floor-length gold coat and jesterly mask, unfurling white-gloved hands with deliberate movements. This is our introduction to the artist. She takes her time, yawning, blowing a kiss, waving and wagging a finger, until the mask comes off and Halprin stares, ready to speak.

In Breath Made Visible, Anna Halprin’s history ambles easily, as if at the dancer’s own dictation. Yes, the implied director and film crew remain concealed for the duration, but no, this never gives the feel of an interview stripped for out-of-context sound bites. It really is Halprin’s story, and it eases along in a cogent, elegant manner. Playful editing bounds from archival footage of stage performances to the artist in her studio, laughing and doing an improvised jig as she recounts: “My mom would say, ‘Why don’t you sit down for one min—!’ And I would say, aw, I just like to dance, all the time for the fun of it!” This is just one facet of Halprin exposed in Breath — one that bears a resemblance to Ruth Gordon’s Maude of Harold and Maude for her natural comedic physicality (in Halprin’s case, dating back to days dancing on Broadway in the 1940s) and an irrepressible joie de vivre.

But Breath Made Visible seeks to cover all of the artist’s many decades as a dancer, beginning with the formative first few: starting with her adolescent discovery of modern dance in the spirit of Isadora Duncan, where she learned she wasn’t ridiculed as she was when attempting ballet. Then, of her training at the University of Wisconsin, which called for human dissection to understand the body’s capabilities for movement. And soon followed her rejection of modern dance pioneer Martha Graham and the legions of carbon-copy disciples Halprin felt had unforgivably abandoned the foundational tenant of creativity.

The joys of Breath Made Visible are pure and numerous. The film proffers generous handfuls of footage from stunning performances spanning Halprin’s career. Conversational contributions are interwoven from her two daughters, Daria and Rana; from early collaborators A.A. Leath and John Graham; and from husband Lawrence Halprin, the influential landscape architect with whom Halprin clearly shared a profoundly symbiotic creative relationship. And throughout, Halprin never stops moving. She tells us that dancing isn’t about how you look, but how you feel. In the mid-1960s, she feels charged with the energy of the Watts race riots; after her break with Leath and Graham later in the decade, she’s blissed out within her commune-like home environment. And in 1975’s Dark Side Dance and 2000’s Intensive Care, Reflections on Death and Dying, she’s filled with all the rage, fear, and grief of the prospect of impending death, from struggling with and beating cancer to later seeing her husband in the hospital. In her eighth decade (and approaching her 90th birthday this July), Halprin engages with the aging body — her own and others’ — where the dance world typically stops short.

“We tend to think of dance in a very limited way, we think of it as something that just exists on stage. Dance has always been connected to very young bodies, and being a senior myself, I wanted to give them a voice,” she says, introducing footage of her moving 2005 piece Seniors Rocking Performance and Filming. The most important thing that Breath Made Visible does so well is render the spirit of Halprin’s singular approach to her work in an emotionally palpable way. Shots of sunlight playing through tree branches are paired with Halprin demonstrating how, by allowing her consciousness to come to that tree, her movements stretch naturally treeward. Or how when she and Lawrence sketch a poster graphically depicting “The Creative Process,” Halprin wonders whether it shouldn’t read “A Creative Process,” — because otherwise, “That makes it sound like it’s the only creative process in the world.”

Breath Made Visible blissfully documents not just Halprin’s life and chronological oeuvre, but the shimmering evolution of how she relates to and engages with her art. And the film does so by artfully employing its own medium, that which is so uniquely suited to capturing and reproducing motion; it’s a perfect space for her continuing legacy to move and breathe.