One of the more talked-about scenes in Buzzard is the one in which Marty Jackitansky (Joshua Burge) sits on the bed of a posh hotel, in a white robe, shoveling an entire plate of spaghetti into his mouth. But the particular nuances of the scene reveal that what may, on the outside, seem like a pretty cheesy and unfunny attempt at comedy is actually “cultural commentary.” See, Marty starts off eating the spaghetti by delicately spinning his fork and lifting it gently to his mouth. But he soon loses patience for this and begins scooping the spaghetti with the fork and knife into his mouth, taking bigger and bigger mouthfuls as the noodles fall onto his chest. Director Joel Potrykus lingers on the shot, not cutting away. He isn’t condemning this, and he isn’t celebrating it either. He is just showing us how we are — glutinous, impatient, and ugly.

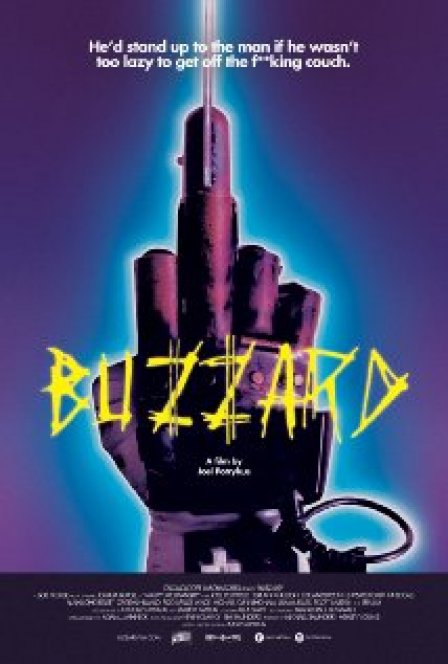

Buzzard is the third film in Sob Noisse’s Animal Trilogy, following Coyote (2010) and last year’s superb Ape. Like those films, Buzzard stars Joshua Burge as an outcast who in some way resembles the eponymous animal. Taken together, the films have gradually etched a manifesto for the millennial slacker. Here Burge plays Marty, a twenty-something who’s more than dissatisfied with his corporate temp job. He loves 80s horror, DiGiorno pizza, and modifying his Nintendo Power Glove into an increasingly realistic copy of Freddy Krueger’s trademark claw-glove. But what Marty spends most of his time doing is pulling off small-time scams, whether return fraud at office supply stores or illegally signing checks over to himself. When he finds out that this latest scheme is easily traceable and his days of freedom may be numbered, he quickly goes on the lam. First he shacks up with office buddy Derek (played by director Joel Potrykus), but then moves out and tries to get by on his dwindling cash reserves. His situation gradually deteriorates, and he is forced to resort to larger and more serious crimes as he becomes increasingly desperate.

Though much of the film is a social commentary, part of what makes it tolerable, and in fact enjoyable, is the lack of a moralistic high ground. Rather than telling us that thirty year-olds living at home playing video games and surviving on Totino’s and Mountain Dew is a bad thing, Potrykus instead just presents this as a new reality, the new world order of 2015. Much of this material is used for its comedic value, and Marty’s work friend Derek is laughably sad in both his exclusion from society and also his willingness to suck up to his corporate superiors. But even though Marty spends the majority of Buzzard being an unlikable jackass, when the tables are turned and a convenience store cashier swindles him out of five bucks, we empathize. This is not because we condone Marty’s actions, but because we are also in debt and working shitty jobs in retail, food service, or as temps. Marty’s phone conversations with his unheard mother, in which he lies about receiving promotions and raises, will resonate particularly well with anyone who has had to respond “No” when their mom asks, “Did you apply to any jobs today?”

The film for the most part stays away from the magic realism of Ape (an unfortunate decision, in my opinion), though Buzzard does retain the symbolism of a wound that worsens in accordance with Marty’s actions and his descent into hopelessness. Like Ape, there are plenty of cringe-worthy moments; to create something cringe-worthy on purpose, that effectively instills the dread that accompanies secondhand embarrassment, is truly remarkable. There is a great moment when Marty returns to the office supply store where he frequently commits return fraud, only to find the unwitting employee has been replaced by a much more competent one, who is less ignorant of Marty’s intentions. The exchange between Marty and the new employee, in which both know of the others intentions yet do not outwardly acknowledge it, is excellent in its awkwardness. The scene is so difficult to watch because of what it says about us; that we are willing to screw over our fellow men, so long as they don’t think less of us for it. But the sobering reality of Marty’s victories is that the money he steals isn’t even a drop in the bucket compared to the companies from which he steals. Remind me again who’s the buzzard and who’s the carrion?