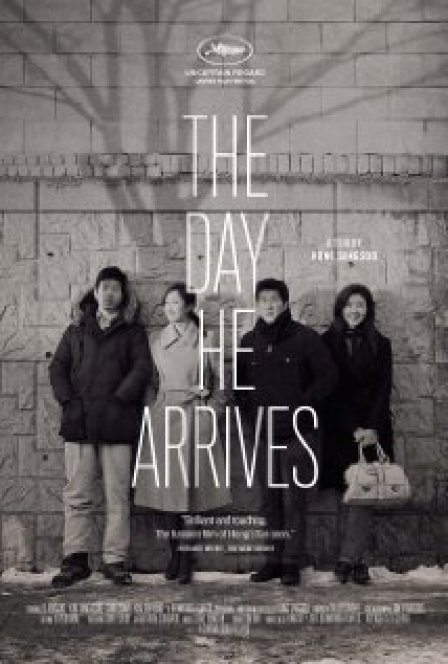

What Hong Sang-soo lacks in variety, he more than makes up for in completeness. After Oki’s Movie (TMT Review), a film that explores three filmmakers in various stages of their careers, Hong offers The Day He Arrives, an examination of a man who has abandoned filmmaking for the solace of the classroom. Coming as it does during the brief interlude between Oki and the upcoming In Another Country (Hong’s first Palme D’Or contender after several lower successes at Cannes), The Day He Arrives serves as both a coda to its immediate predecessor and as a look at one of filmmaking’s alternative paths: that of the failure.

Young, charming, and a heavy smoker, Sungjoon (Jun-sang Yu), who previously made four films in Seoul before becoming a teacher out in the country, has returned to the city for a brief visit. His trip to Seoul is indeterminate in all ways: he’s not sure why he has returned, how long he’ll stay, or who he’ll see. On his first day, he cannot find his one close friend in the city, so he gets drunk with some film students before turning up on an ex’s doorstep. The next day, he gets drunk with his friend and finds a girl who looks exactly like his ex. The third day is the same as the second. The pattern Hong creates for Sungjoon is unsubtle, as are most of Hong’s filmmaking decisions: cameras are planted and shots are reused in order to drag the viewer’s attention to the characters’ unrelentingly awkward interactions. Sungjoon’s inability to say (or even know) what he means in most instances is an acknowledgement of one of Hong’s stylistic trademarks: an insistence that characters translate aloud only a fraction of the maladroit calculus going on in their minds. In this exacting document of everyday life, subjects are changed, questions are ignored or not answered, and difficult situations get defused.

Hong leaves most details of Sungjoon’s life and work tantalizingly undefined. As he wanders the city, Sungjoon encounters (on four occasions) an actress he’s worked with before, gets harangued by a former leading man, and meets only one person who recognizes him as a filmmaker (despite getting drunk with a few film students who happen to know his work). Why he left filmmaking is never explored, and Sungjoon ducks the awkwardness of unwanted conversations with total gracelessness. It’s a convincing portrait of an artist alienated from his own medium, albeit one that frustrates with its constant reiteration. Even more aggravating is the approach Sungjoon and his friends have toward women: the film’s men repeatedly announce the basic simplicity of women, while Sungjoon beds several through a combination of bashfulness, persistence, and his reputation as a filmmaker. A common current in Hong’s filmmaking (and one pointed out regularly in criticism thereof) is the presentation of filmmakers as inherently successful with women, no matter their professional success. It’s not unlike the patterns found in the work of Woody Allen or Philip Roth.

Hong’s awareness of Sungjoon’s faults doesn’t exonerate either man. When it succeeds, The Day He Arrives does so in spite of this fact, with Sungjoon’s literal and metaphorical aimlessness becoming a self-contained purgatory. Sungjoon cannot speak clearly on any subject, and his retirement from filmmaking seems more a result of running out of stories to tell than the inability to tell them — failure wrought from confusion rather than crisis. The film closes with a fan of Sungjoon’s approaching him in the street, asking to take his photo. The former filmmaker has no idea how to situate himself in front of the camera, acquiesces to direction reluctantly, and cannot find his way to comfort. It’s as honest an encapsulation of Hong’s career of quasi-autobiography as can be found in The Day He Arrives, but it’s difficult to welcome the argument that honesty is all that’s needed to make a film good.