Ever since The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, there has been an ever-widening gap between Wes Anderson’s fans and his detractors. A wunderkind and director of two of the best comedies of the last 15 years with Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums, Anderson of late has become too rigid — his aesthetic and thematic preoccupations too limiting, his affectations too broad — to accommodate the emotional poignancy of his earlier work. Or so the story goes. I, along with many other Anderson fans, stood firmly in the auteur camp, finding that each subsequent film added shades and layers to his oeuvre of dysfunctional families, troubled youth, and offbeat surrogacy. Even in Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson’s least successful effort to date, there are still enough choice moments and idiosyncrasies to almost forgive its most glaring faults. Of course, given the almost unanimously positive response at Cannes and from other critics, I’m starting to feel like the only one who sees faults where everyone else sees a brilliant return to form.

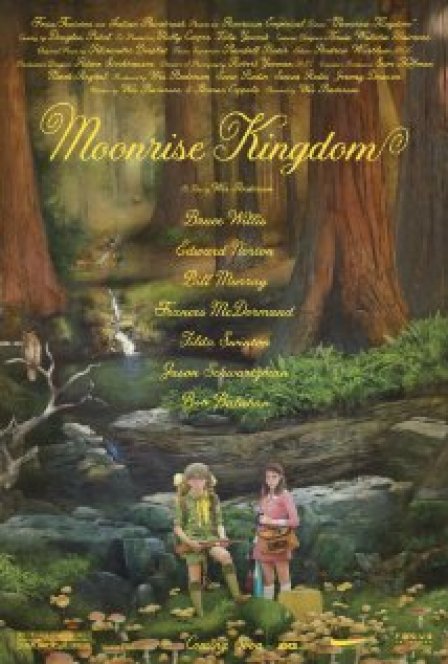

Set in a remote New England town in the mid-60s, Moonrise Kingdom centers on a love affair between Sam (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward), two precocious 12 year olds who run away together only to be tracked by Sam’s Khaki Scout troop, Suzy’s parents, a local sheriff, and social services. Anderson’s typically quirky array of characters is played by one of his most impressive, or at least most unique, casts to date. Newcomers Tilda Swinton, Edward Norton, Harvey Keitel, Bruce Willis, and Bob Balaban, whose brief appearances were a major highlight, join Anderson mainstays Bill Murray and Jason Schwartzman. Some (Norton and Balaban) fare better than others (Willis and Keitel). But in the film’s ensemble scenes, the actors never quite seem to gel into a cohesive whole. It’s as if instead of seeking to match this film’s unique tone, they all simply rely on their own interpretation of Anderson’s quirk. This doesn’t so much hurt individual scenes as it does the film as a whole, which feels a bit like patchwork both in its heavy borrowing from the director’s back catalogue (imagine young Max Fisher and Margot Tenenbaum’s running away together) and its various tonal clashes.

While Gilman and Hayward, the two child actors, are able to hold their own in ensemble scenes, the numerous conversations between the two of them often come off as forced, with a flatness of delivery bringing the written word itself to the forefront. And it’s unfortunate, too. As much as Anderson’s earlier scripts were vital to his film’s successes, the script of Moonrise Kingdom is central to its failures. Structurally, it’s interesting how he works into the mix elements like the opera from the film’s early moments and the fantasy novels Suzy likes to read; along with the impending storm, they give the film a fable-like feel. Yet the story, and its drama, carries little weight. That’s partly due to the mismatched performances, but it’s also due to a script’s failure to flesh out its two protagonists or even show much interest in their situation or surroundings. As a result, their love-on-the-run escapades aren’t nearly as emotionally engaging as they’re meant to be. While Anderson’s auteurish impulses create a number of genuinely tender and clever moments — particularly the piercing of virginal earlobes in one scene — these are undermined by the two-dimensionality of nearly everything else.

Anderson’s quirky, droll humor is present — in spurts, at least. But because of Moonrise Kingdom’s disingenuousness, the film is drained of the emotional weight it could have had. What’s left besides Anderson’s trademark superficial pleasures is simply hollowness. Ironically, most of these complaints are similar to those that I defended Life Aquatic and The Darjeeling Limited against, but this film’s few real sparks — like the beautifully piercing waterside dance scene — only reminded me why I love Wes Anderson at his best, thereby emphasizing the many deficiencies at hand. For the first time, Anderson’s artifice has worked against him.