In the second volume of Miguel de Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote, the titular Quixote and his sidekick Sancho Panza find themselves unexpectedly famous, their previous exploits widely known by the characters they encounter on their travels. Everyone’s read about them, it turns out. The duo visits a printing press — a fairly recent invention — and discovers that it’s churning out the first volume of Don Quixote, which, in real life, was published 10 years earlier and which, presumably, the real life readers of the second volume had recently finished reading. Upon examining a copy, Quixote claims it’s not very accurate. The joke’s on us.

Published in the early 17th century, Don Quixote is widely regarded as one of the first modern novels. Yet it destroys more narrative conventions than it creates — those of the picaresque genre it satirizes, and particularly those that it itself relies on. Its own narrative layers, and even the division between readers and characters, are as likely to be rendered impossible as they are to be used as organizing structures. Modern narrative, it seems, was born with a taste for destruction, especially its own. That’s one reason we like to watch. A snake swallowing its tail. A banana tripping on its own peel.

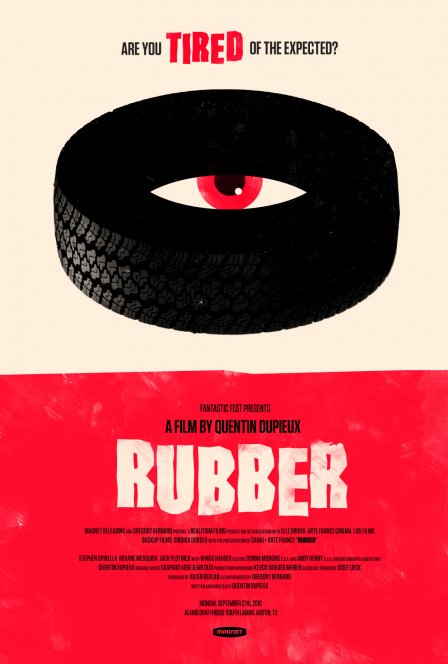

French director Quentin Dupieux’s new film Rubber gives us a double-dose of destruction that’s much in the same vein. There’s a tire, named Robert (try saying that with a French accent) in the film’s credits, who miraculously lifts himself up out of a desert junk pile and rolls around gleefully blowing stuff up with his mind. There’s also the film’s narrative self-destruction, which occurs in both slow unravelings and fairly sizeable explosions. Somehow, it feels as if the two aren’t unrelated. Dupieux has said that his primary inspiration for Rubber came from Steven Spielberg’s 1971 TV movie Duel, in which a truck goes on a rampage. Both Robert and Rubber are made from the post-consumer remains of a genre, reassembled from our culture’s trash.

The film begins with a monologue, delivered by a guy dressed like a cop (Stephen Spinella as Lieutenant Chad) who just climbed out of the trunk of a car. “In the Steven Spielberg movie E.T., why was the alien brown?” he asks, glaring meaningfully at the screen, “No reason.” He lists off more examples. Why did the two characters in Love Story fall in love? Why was the president assassinated in JFK? Why doesn’t anyone ever use the bathroom in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre? Why does the main character in The Pianist have to hide out and live like a bum when he plays the piano so well? Each time the answer’s the same: “No reason.” All great films, he tells us, contain an element of no reason, an “element of style” to which the following film is an homage. Then he dumps the glass of water he’s been holding onto the desert sand and climbs back into the trunk of the car.

It’s hard to bust a gut and think deeply at the same time, but you don’t have to struggle between the two for long — throughout its 85 minutes, Rubber is nearly always hilarious or thought-provoking. The camera pulls back to reveal that the monologue we thought was for us was directed to an in-film audience, a bunch of spectators gathered in the desert to watch events unfold. These viewers are handed binoculars by the Accountant (Jack Plotnick) who, pointedly, seems to be the one in charge of the audience. Soon, one of them spots the tire. At first wobbly and tentative like a foal, Robert’s soon crushing plastic bottles and blowing up any living creature he comes across. The tire doesn’t actually do much — it just rolls around and, before it makes an object explode, vibrates — but Dupiueux, who’s also the film’s cinematographer and half of its music team (along with Gaspard Augé), uses cinema’s simple tricks to breathe much life into him. Surprisingly, it’s immensely pleasurable to feel like you know what a tire’s thinking just because of the way a camera frames him. When Robert blows up his first kill, an unlucky rabbit whose explosion is a thing of beauty, he does a little victory dance. The joy is palpable and contagious.

The tire finds a hot girl (Roxane Mesquida as Sheila; the audience debates her physique during her shower scene) driving through the desert in a convertible, follows her, and checks into a motel room next to hers, killing people and making use of the facility’s pool along the way. Robert even enjoys a shower. As the film rolls masterfully through this familiar genre territory, the in-film audience provides occasional commentary, amusingly predicting real life audience responses. Nothing’s happening. I’m hungry. This is boring. A couple of nerds debate the correct term for blowing shit up with one’s mind. But the Accountant serves an unseen Evil Master, and he serves the onlookers a poisoned meal. The only one who doesn’t passively eat what the money-cruncher feeds him is Man in a Wheelchair (Wings Hauser), who just wants to be left alone to watch the mayhem.

It’s not only the Accountant who wants to get rid of the audience as quickly as possible. Lieutenant Chad (who, it turns out, is the film’s director, of sorts) has been counting the time till the viewers are supposed to be dead so that he can call off his squad’s search for whoever has been exploding all the heads in town. But Man in a Wheelchair’s survival has messed everything up. Eventually, the lines between performers and observers disappear, as audience and action converge. Even despite Rubber’s camp, it’s chilling when the monster we had been rooting for finally turns on those who, according to the film’s own logic, should have been off limits. The joke’s on us; laugh uneasily.

Rubber never feels like simply a parody of a 70s road horror film. The acting, while often hilarious, is more detached than melodramatic. Scrub landscapes and stylish motel furnishings capture Dupieux’s eye just as much as gore, which itself is near exquisite. Far from being propelled by contrived horror, it seems as if the film unfolds tortoise-paced, on the verge of disintegrating into the desert’s emptiness. But the space just makes all the chuckles and holy shit moments resonate.

Don Quixote’s trick on its audience would have never been possible without the printing press, a technology that transformed the public’s access to narratives that had only fairly recently saturated Spain. In a surprise second ending, Rubber’s inanimate monster sets its sights on Hollywood. Although you’d never know it, Dupieux made the film on a consumer-grade digital camera.