In his new film Septien, triple-threat Michael Tully writes, directs, and stars in a hazy, gorgeously weird story of trauma and redemption. The film is premiering in Park City as well as on VOD as part of Sundance Selects, and though their super-16mm footage deserves a larger screen, I wouldn’t shy away from watching it on late-night television. In fact, Tully lists 80s made-for-TV movies as an inspiration. Don’t be put off — there are moments of genuine emotion, but there’s nothing remotely contrived or ironic about this family drama. Unlike tired mumblecore fare, this is a specific, articulate film with a throbbing heart — and other appendages on prominent display. If you’re up for an evening of Southern Gothic, pour a whiskey and let this funny, troubling film pull you under.

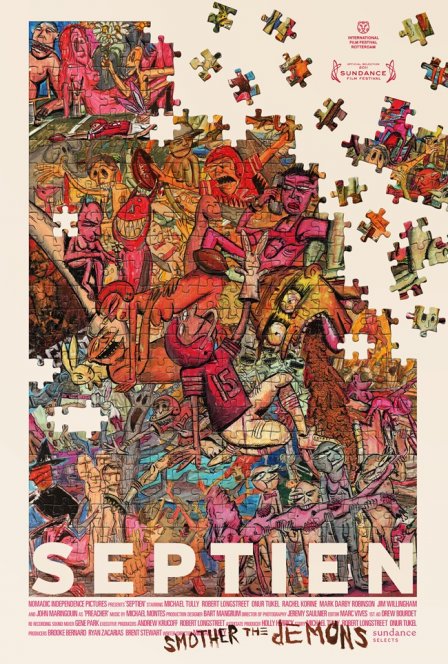

The story more or less begins with the return of Cornelius Rawlings (Michael Tully), after 18 dark and soundless years, to his brothers and their ancestral home, a creaking, dilapidated house in the overgrown tangles of the unnamed South. In his exile, Cornelius left behind two elder brothers, Ezra (Robert Longstreet) and Amos (Onur Tukel). Ezra is the frustrated “housewife,” the brother who cooks, cleans, and generally keeps it all from going to the dogs. Amos, the tortured artist, holes up in the barn where he creates furious, explicit artwork, childlike drawings full of perverse, scatological imagery — and football? It is clear that they are a damaged and fragile clan, marked by some past, adolescent evil. Each boy copes in his own way: Ezra scours like Lady Macbeth; Amos clings to life through his work; and Cornelius, when not observing the madness with sage, silent eyes, alternates between hustling for money and hurling himself into substance-induced blackouts.

It’s not what you think — one of the film’s funnier twists is that Cornelius’ hustle is athletic rather than sexual, and his drugs of choice huffed gasoline and malt liquor. Okay, that doesn’t sound that funny, but trust me, it’s hilarious. And then sad. And then hilarious — an elegant and surprising emotional flicker that the film manages to sustain even when drifting into the darker waters of repression and abuse. Ezra perhaps puts it best when he wails, amidst the refuse of their faulty plumbing, “It never ends, the filth!” Even so, Cornelius’ return amounts to an exhumation of their demons, and this leads, somewhat predictably, to a catharsis. I was less taken by the film’s closure, perhaps because what precedes it already feels so complex and, in its own way, whole.

The story was apparently a collaborative effort between Tully, Longstreet, and Tukel (also a filmmaker), and their shared investment in the material shows. All three commit fully to their characters, and give strong, honest performances. Tully in particular uses his body to full advantage, in movements ranging from gracefully athletic to feral, to flesh out a virtually silent character. Harmony Korine’s wife Rachel makes an appearance as female innocence incarnate, and musician Jim Willingham plays their simple farmhand Wilbur. Coach Rippington, the dirty old man they must confront, is given croaking life by Mark Darby Robinson.

Director of Photography Jeremy Saulnier (whose work I admired in Matthew Porterfield’s Putty Hill) adds his beautiful, confident camerawork. He is not afraid of handheld but also knows when to back off, shooting characters from behind or enclosing them in doorways or structures within the frame. This contributes to the sense that the world created within the film fills and flows past the screen. This flow is also carried by the full soundscape of insects, lashing rainstorms, and trucks on dirt roads — the orchestral hiss, rot, and drip native to the South. In short, this film is an experience, full, perhaps overripe, but a welcome antidote to more typically anemic independent fare.

Tully has admitted to striving for both “an accessible and funny art film” and “a wholly genuine and sincere portrait of male repression.” Much like Black Swan, with its neurotic ballerina, and her feathers, mirrors, and blood, Septien gives us the Rawlings brothers, with their aprons, sketch porn, and mud. Both films refuse the social contract that demands we keep our psychic discord to ourselves. I like to see this kind of striving in independent film, even more so when it succeeds, as it does so well in Septien.