I signed up for Thefacebook, as it was called back then, in March 2004, when it was limited to only a handful of prestigious schools, all but one on the East Coast. Despite the selectivity, students at my school felt slighted: Dartmouth’s Thefacebook was housed on a separate server, supposedly because there was too much traffic. With a student population of a mere 5,000, some people I knew were convinced that the real reason for our separate-but-equal status was that our endowment was the smallest of all Ivy League schools, and our rankings sure weren’t the highest.

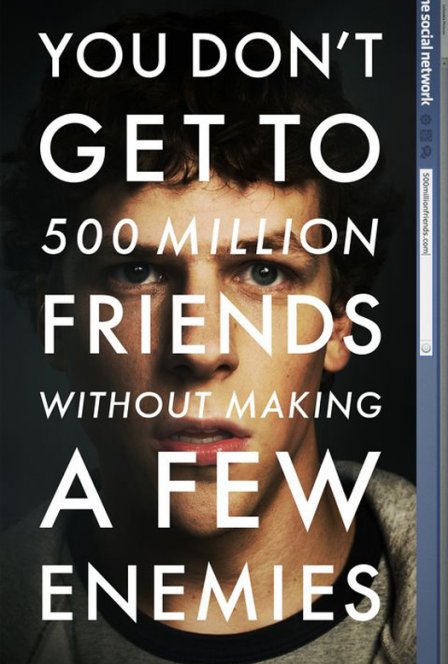

It still seems like a paranoid and petty complaint to me, but it’s illustrative of how people with rank and status can be so obsessed with them. In director David Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s The Social Network, this obsessive quality also serves as the driving force behind Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg).

As the film opens, Harvard undergrad Zuckerberg and his then-girlfriend Erica Albright (Rooney Mara) are having a beer at a crowded Cambridge bar, although how they manage to drink with the dangerous speed of their repartees is beyond me. Zuckerberg’s pondering how to get into a final club, one of Harvard’s eight prestigious all-male “social clubs.” Think frat parties with dress codes and traditions going back over a hundred years. When Albright asks, in an attempt to be helpful, which is the easiest to get into, Zuckerberg’s wounded. Luckily for him, she only goes to Boston University, so she’s easy to dismiss. After an exchange of insults that even Harvard kids wouldn’t be smart enough to think up, Albright leaves the bar and the relationship, giving Zuckerberg this parting gift: Don’t go through life thinking girls don’t like you because you’re a geek, she advises. It’s actually because you’re an asshole.

It’s as much prophecy as it is advice. Next thing we know, Zuckerberg’s drinking alone while insulting his ex’s “barely there” B-cups on his LiveJournal and coding a webpage that puts images of Harvard girls (that he hacked in and stole) side by side, letting users vote on which one is hotter. Within a few hours, the site’s popularity crashes the server. Zuckerberg’s disciplined by the university and vilified by women’s groups, but as it turns out, being an asshole and being respected aren’t that different from one another. While he brags to the disciplinary committee about the hacking skills his stunt demonstrated, the real genius — what soon scores him friends, recognition, and segues into the creation of Facebook — was in the concept: watching people we know in real life “fight,” from behind the safety of our screens.

It’s the growth of that misanthropic yet visionary idea that propels the rest of the movie. While the film doesn’t give us any information that can’t be gleaned from a few minutes reading one of the numerous profiles that have been published on Zuckerberg and Facebook, Fincher and Sorkin do a masterful job of organizing the real-life biographies of Zuckerberg, his friends, and his associates around the opening scenes’ themes of privilege, exclusivity, and inadequacy. Of course, the film’s also entertaining, making computer programming as dramatic as it could possibly be onscreen, using flashbacks and flashforwards to multiple pseudo courtroom dramas to keep us awake when Zuckerberg’s (totally accurate) monotone threatens to do otherwise. It’s also full of equally over-acted performances. The Social Network is slick, weighty, and as satisfying as piecing together acquaintances’ hookups and feuds from cryptic status updates and flirty notes posted to their walls.

And perhaps just as useless. After all, the Facebook that the film describes no longer exists. Zuckerberg’s rise to youngest billionaire in the world necessitated that his company ditch exclusivity in favor of the masses. In 2004, Facebook was a good way to see who that cute person in your English class was. Now, it’s a good way to see how your grandparents are holding up.

Two other films released this year have taken up web 2.0 in greater detail, and both were pretty much ignored. We Live in Public, a documentary about forgotten early web pioneer Josh Harris, who broadcast his whole life online to disastrous results, preached about how the internet has changed our ideas of privacy. 140, currently making festival rounds, uses Twitter’s character limit as its own formal constraint, as 140 directors each film 140 seconds simultaneously. But the most high-profile piece of filmmaking to deal seriously with the virtual world of web 2.0 is more concerned with two very particular landscapes than any kind of globalizing e-culture. The Social Network gives us plenty of the tradition-bound privilege of Harvard University and nearly as much of Silicon Valley’s fickle casino of tech. As for Facebook’s own peculiar geography, it’s simply not that interested. It’s hard to tell whether that’s a blessing or a missed opportunity.