In the mid-1500s, Michelangelo — already established as one of history’s great artists with the Sistine Chapel ceiling and sculpture of David behind him — witnessed a group of upstarts imitate his style by exaggerating his forms and techniques, a respectful kind of parody that earned the title of Mannerism for how these painters worked in the “manner” of their esteemed predecessor. Rather than ignoring or rejecting the younger generation, the aging Michelangelo in turn altered his own artistic style to reflect the influence of those who had been influenced by him.

Whether or not Martin Scorsese knows this particular tidbit of art history (let’s be generous and assume he does), the later stage of his career has followed a similar course. In the 80s and 90s, the Hong Kong New Wave directors and American independent filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson started making films that owed a formal debt to Scorsese, incorporating the quick edits, slow motion, fluid camerawork, and stylized violence that had by then become emblematic of Scorsese’s cinematic legacy. After some stylistic forays, notably the toned down pacing and saturated colors of both Kundun and The Aviator, Scorsese seemed to acknowledge the reach of his own influence by releasing The Departed, a remake of a Hong Kong crime film that was itself Scorsese-esque. In reinterpreting a work that was essentially drawing on his own films, Scorsese heightened the “Scorsese-ness” of the film, turning the street-level neorealism of his earlier works into a grandiose tragedy.

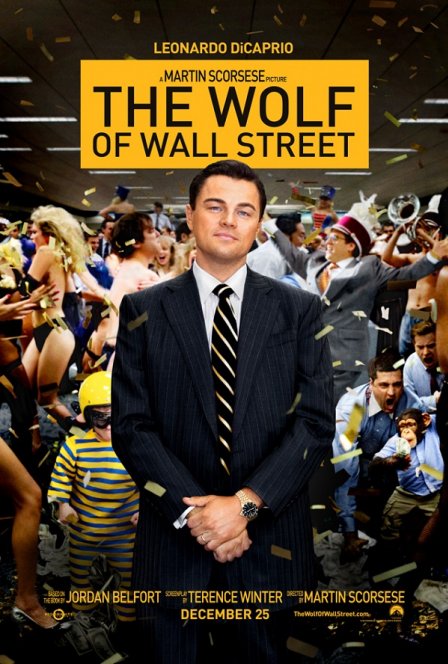

In The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese is working along the same lines. If Boogie Nights alluded to Goodfellas as its inspiration, Scorsese has refracted that influence back into this film. Anderson’s ode to 70s excess cut scenes into montage at a dazzling pace, while the camera famously glided through the San Fernando Valley homes and clubs as though it were dancing along with its characters. Here, Scorsese edits the life of Jordan Belfort (Leonardo Dicaprio) with its encapsulation of Wall Street’s greed and gluttony in an extended series of quick montages and vignettes; the intentional repetitiveness of these scenes along with the film’s resistance to the traditional character arcs and moral realizations counterbalances this pace. There is a straight line to Belfort’s story, but Scorsese rejects it: he jumps around in time and place as he (and screenwriter Terence Winter’s excellent adaptation of Belfort’s own book) sees fit. Just as in Goodfellas, Scorsese employs his antihero as narrator, yet he allows Belfort more room to navigate, in some cases literally as Belfort breaks the fourth wall and beckons the camera to follow him. By empowering his narrator cinematically, however, he merely conveys Belfort’s unreliability: instead of elevating Belfort to the epic figure he imagines himself, Scorsese’s film presents him as a buffoon.

As a filmmaker, Scorsese, like many of his other New American cohorts, lingered on the edge of modernism. His use of popular music in soundtrack and technical innovations may have pushed film towards postmodernism, but for the most part, he remained mostly a bystander. As a film scholar and historian, Scorsese selected his influences carefully from the annals of cinematic history. In this film, however, Scorsese embraces the “low culture” sources championed by post-modernism. There are references to MTV, Miami Vice, and, perhaps most brilliantly of all, a drug-injected Popeye the Sailor Man. In many scenes, Scorsese frames Belfort in the vernacular imagery of rock stars and hip hop music videos. Yet Scorsese understands that the latter create objects of value, while Belfort is simply a con man masquerading. At Belfort’s moment of “downfall,” Scorsese recreated a TV promo, with the camera falling to Belfort’s level. This moment perhaps reveals Scorsese’s greatest horror of all: the glorification of celebrity without merit has debased the auteur culture. If Scorsese’s last film (Hugo) overly nostalgized film culture, his latest laments its decline. Perhaps, in continuing to reflect on his own influential status, Scorsese is wondering about his authorial presence, whether the next Scorsese might be relegated to producing reality television.