“People are terrible. They can bear anything. Anything! People are hard and brutal. And everyone is disposable. Everyone! That’s the lesson.” —Rainer Werner Fassbinder

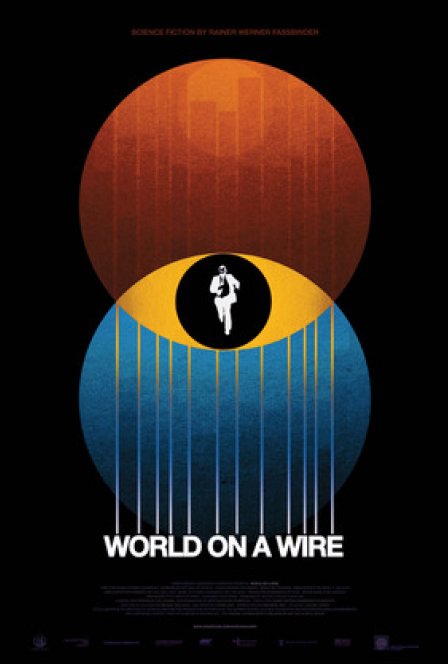

While the above quote wasn’t written specifically in reference to World on a Wire, it may as well have been. Originally released as a two-part German miniseries that aired in 1973, Fassbinder’s sci-fi adaptation of criminally under-valued New Orleans author Daniel Galouye’s 1964 novel Simulacron Three is as much about the absurdity of certainty and the essential futility of human action as it is about the difference between reality qua reality and virtual reality. And while one could quickly (and rightly) point out how capable these lofty concepts are of imbuing the work with some undue (boring) heft, the film actually clips along quite nicely throughout its nearly four-hour runtime. Lost for decades and recently restored, this proto cyber-punk experiment of Fassbinder’s has surely earned its place alongside the director’s more critically acclaimed works.

At a pioneering technological company in urban Germany in a not-too-distant future, the lead architect of a groundbreaking new social modeling system mysteriously dies right after a nonsensical and hysterical rant about mirrors and their symbolic relationship with existence to the president of the company and government officials who are bankrolling the project. This tragic event is the catalyst that allows Fred Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch) to take over the project, which he’s only so happy to do, seeing as his natural state seems to be murkily brooding, feeling that his talent is being squandered, and feeling nonplussed when lusty blondes offer to sleep with him. The first half of World on a Wire does an excellent job of drawing its audience into an intriguing story of Stiller’s ambition and attempts at triumph over adversity through establishing a classic noir mystery with some avant-garde visual flourishes, which sustain its believability when the theoretical stuff comes into play later.

It has always struck me as kind of tragic that the lion’s share of well-known dystopian futures’ antagonists are evil on a very basic level. That is, they’re nefarious and brutal and exist to control/harm people for whatever malevolent purpose strikes the most presumably visceral fear into a given audience during a given epoch. And so it is to Galouye’s (and, by extension, Fassbinder’s) credit that the antagonist in World on a Wire is something as mundane and ever present as marketing. Market research provides the impetus to create a virtual world that can predict, for commercial interests, what people will want/need to buy in 20 years. It is not despite this ostensibly harmless purpose that things go awry, but precisely because of it.

The stroke of genius in the film, in contrast to the novel upon which it’s based, is Fassbinder’s refusal to just come out and say whether he believes himself that humans are totally predictable (the very presupposition of the Simulacron machine in the film) or if he feels that a system based upon the idea that humans are totally predictable is totally abhorrent. Over and above this unanswered question, the evil in this film is just about as banal as it gets; the anguish and suffering and dread that Stiller experiences in this film are all attributable to a government’s pragmatic and morally neutral collusion with private enterprise. Prescience, anyone?

Technically, World on a Wire is one of Fassbinder’s great achievements. The performances in this film are rock solid, which is pretty remarkable considering the amount of unnatural blocking Fassbinder employs during long conversations between principal characters. There is a blatantly obvious visual motif involving mirrors that, in a less capable director’s hands, could’ve detracted from the experience of viewing the film to the point of making it unwatchable. However, Fassbinder repeats and varies this technique to such an extent and to such a degree that it becomes hypnotic and just as central a part of the film as the story and the actors.

World on a Wire deserves a lot more respect than it received when it originally aired and during its subsequent overly long exile from audiences the world over. The film is a dystopian masterwork that cuts to the heart of what is legitimately terrifying about a large, bureaucratic/corporate entity in some vague future sure to rob good folks of everything decent in this world. There is no smirking Mr. Smith or smug Colonel Sanders to personify evil in this film. The real heart of darkness that Galouye and Fassbinder are getting at is a fascistic partnership completely blinded to the uniquely human by its ostensibly well-meaning desire for efficiency and general prosperity. Also, try your best to forget that one time you watched The 13th Floor because you thought Gretchen Mol was a total QT. World on a Wire is nothing like that movie. Nothing like that movie at all.