When The Mix was released in 1991, it created an irreversible divide between fans who were willing to accept new material, regardless of the form it took, and those who were disgusted by the very thought of a pseudo best-of. Throughout a sweeping gape of the 1970s, Kraftwerk had positioned themselves at the forefront of electronic music in using synthesizers and drum machines to create compositions that set a benchmark for the hordes of aspiring electronic acts that were to follow. The Mix was seen as a turning point because it saw the group demonstrating a desire to revisit past material and identify with their music through a new context. Although this may appear to have been industrious at the time, by that period, their back-catalog had achieved cult-classic status, which meant they were altering their history in ways most fans were not ready for. The Mix was widely shunned by dedicated followers and critics alike, not only because it saw the band looking backward, but because Kraftwerk’s ‘greatest hits’ were being tampered with.

Announcing the leap from analogue to digital recording on the album also symbolized a desire to drive forward technologically — ambition derived from intent to reshape the dimensions of those classics in a way that should have improved sound quality and allowed for fans to experience Kraftwerk in a contemporary light. That never really happened though. Despite the fact that a number of tracks were subject to a dance floor-oriented shift, the mastering of the record left plenty to be desired. It sounded flat, half-baked. The group’s signature tracks had been sacrificed on the alter of remix without yielding particularly pleasing results, and that was enough to push the hardcore over the edge. The Mix consequentially went down as an unjustifiable failure — a step in the wrong direction. So why would anyone in their right mind chose to see that troubled regress performed in its entirety over any of the master works?

For a generation of listeners born after the heyday of Trans-Europe Express, and who grew up in a world coming to terms with the scope of electronic music and its capabilities, The Mix was a solid introduction to the efforts of the very outfit that had kicked things off way back when. The album worked as an embodiment of manhandled success that shed light on previous material in a way that demonstrated Ralph Hütter and Florian Schneider’s willingness to experiment — all this at a time when the remix was a standard format on cassette and CD singles. Indeed, this was my initial experience with the band, and one of the central reasons I chose The Mix as the album to see performed live at Kraftwerk’s recent Tate Residency.

The London shows took place 10 years after the group’s most recent release, Tour De France, and showcased every other studio effort from 1974’s Autobahn hence — eight albums, eight nights. Each performance promised two hours of music, including every track from the album of the day plus a selection of hits with improvisational fragments and state-of-the-art 3D visual effects. The concept sounded amazing when it was announced, and despite the fact that Kraftwerk had already conducted similar performances in New York and Berlin, when the London tickets were released, the Tate website crashed at the hands of rampant admirers desperate to spectate.

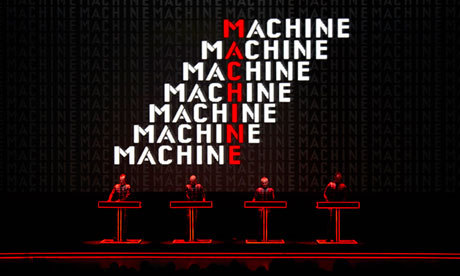

The Turbine Hall is a cold and hollow space that works tremendously well as a makeshift stage. As we approached, the chimney protruding from the main building seemed so fitting amid the grey clouds that shuffled overhead it might easily have played a forgotten factory wherein a collection of neglected showroom dummies had been left to decay, only to come alive at night and perform electronic music for a starstruck selection. I had read a number of reviews about the concerts leading up to Night Seven and had a good idea of what to expect: 3D glasses, a black cushion, and a sold-out show that gradually shapeshifts through the album’s tracklist before spinning out into a panoply of hits. However, nothing can quite prepare for a 120-minute spectacle fronted by four men wearing illuminated lycra bodysuits, standing in front of their keyboards and pummeling their audience with cyberling techno classics.

The lights went down and a stern robotic voice projected over the audience: “Ladies and gentlemen” (something in German… something in English), “K R A F T W E R K” — the black drape covering the stage fell to the ground and “The Robots” burst across the venue. It might have been a pumped-up version of the original, but it sounded impeccable with the surround sound set up. The 3D spectacle displayed vintage cuts of mannequins moving their limbs slowly to the thumping drawl of the 1970s classic in an overwhelming surge of nostalgia as Ralph Hütter gingerly manipulated his keys alongside new recruits through the track’s iconic refrain.

After a beautiful rendition of “Computer Love” the momentum of “Autobahn” started up. It’s a track I have been told was revolutionary when it first hit the shelves on vinyl, for if you placed your speakers in the right place when listening to it, the fact that you could hear the cars zooming from one side of the room to the other was considered a mesmerizing party trick — all you had to do was shut your eyes and pretend you were on some sort of mad electro highway. I hadn’t imagined that shutting my eyes would be in the cards this evening, as the 3D visuals were supposed to be a component to behold. However, the MS paint VW that trundled along a cartoon road looked like it had come out of a kid’s TV show — it was a big disappointment that was only half-rescued by a shot of a dashboard and a gloved hand, which slowly turned up the volume to produce a series of music notes that poured out onto the audience to brilliant effect.

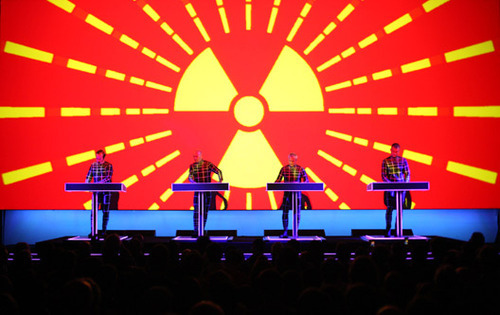

By the time “Radioactivity” kicked in, even the sight of people lifting their mobiles every few minutes to share the moment on Instagram could not taint my elated state. This was the track I had come to see, and it went down an absolute treat. It was one of those transcendental ‘wow’ moments that got me thinking, “Am I really here?” “Am I really experiencing this?” The croaking, mechanical voice “Stop! Radioactivity” and the humanized vocals that follow it’s in the air for you and me made this enough of a protest song without the inclusion of “Fukushima” to the laundry list of power plants Hütter reels off as names appears on the screen like newfangled superstar brands — “Tschernobyl / Harrisburg / Sellafield / Hiroshima.”

Each of those songs, along with a wonderful version of the “Trans-Europe Express,” “Abzug,” and “Metal On Metal” sequence, all came in the first 40 minutes or so, which left the rest of the show lingering in the balance of untold possibility. Where I disagree with other critics, such as The Guardian’s Michael Hann, is when he suggests the only place Kraftwerk had to go was downhill. How could that possibly be the case when there remained so many directions to take the show in!? As it happened, the second half was every bit exciting as what preceded. The synthetic panache of “The Model,” the cyber dirge of “Spacelab,” and the menacing whir of “Metropolis” were followed by a version of “Man Machine” that was just delightful, the undisputed highlight of the evening embedded deep within a context of glorious techno pop.

The Mix was somewhat disfigured by the songs played between it, but because the album itself lacks any structured narrative, Hütter’s keenness to experiment became easier to observe. The ‘greatest hits’ set-list avoided a strict diet of traditional crowd pleasers, and while the visuals might not have been wholly successful, they complemented certain aspects of the album’s unintentional aesthetic, which was pitted against an ultra-crisp sonic finish courtesy of the Tate audio setup. The evening was a triumph, even if that ropey stretch of “Autobahn” left me baffled, but then again, I could have always closed my eyes.