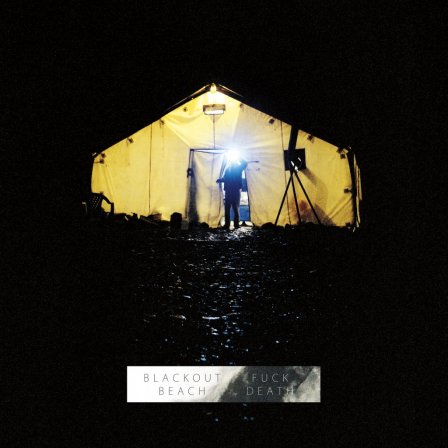

In his most famous work, Being and Time, Martin Heidegger argued that we live in a situation of ‘being-towards-death,’ that death forms a finite horizon within which we can choose to live authentically (Heidegger himself, of course, was notoriously and ambiguously implicated in the 20th century’s most well-known death-dealing project, Nazism). Fuck Death, the title of the latest album by Carey Mercer (a.k.a. Blackout Beach), can be interpreted in various ways: as a rejection of death considered as inevitable finitude in every human project (omnia vanitas), and, at least from a heteronormative viewpoint implicated in the traditions he draws upon, of creation (re/production) as a response to that finitude. But we might also think of a Freudian positing of pleasure and destruction, and the combination of the two, as a ‘necrophiliac relationship’ inherent in the (tragedy of the) human condition.

Mercer sings in guttural tones reminiscent of neofolkies or of goth rock, but his sensibility, though shot through with a heavy ominousness, never invokes darkness in any of the usual clichéd fashions. Here there is a sense of lurking menace, of ambiguous transcendence into light or dark, reminiscent of the smalltown or suburban hollowness of Roxy Music’s “In Every Dream Home A Heartache.” The album is based more around synthesizers than 2009’s Skin of Evil (it’s also far less raucous and rock-oriented than the work of Frog Eyes, another of Mercer’s various projects), but it otherwise doesn’t represent a huge stylistic departure — though, standout track “Hornet’s Fury Into The Bandit’s Mouth” opens with a blackly shimmering blues line before Mercer kicks in with perhaps my favorite lyric of 2011, “You should be ashamed, Philistine,” then whips into a hysterical yet measured passion before returning to earthboundedness, despairing yet reassuring, “walking on the ground.”

Speaking of the Philistines, the references on Fuck Death run the gamut from the Christian serpent to the Greek Agamemnon and Adonis. (Skin of Evil was loosely based around the Greek concept of the ideal woman.) It is in this sense that the music can be considered as owing something to the devotional style, yet at the same time eliding joy and hope. And here, as in Mercer’s obviously and refreshingly deep engagement with the intellect, with poetry, and with literature (Mercer moonlights, or dayjobs, as an English teacher, but sadly these days, that’s no guarantee of those qualities), we see the resemblance to Leonard Cohen, which is also apparent in the gentle female backup vocals that surface from time to time, a Greek chorus of sorts. We also encounter a Medieval or early-modern gothic sensibility (ubi sunt…), evident not only in lyrical concerns with earthly unredeemability (“everyone has sinned”), with symbolism, snakes, and salvation, with the embodied affect of love and mortality, but also in the plucked strings and plainsong-esque synth arpeggios that surface periodically.

Yet these mystical and mythological concerns are intertwined with observations of the minutiae of day-to-day life, with the concrete name(s) of female acquaintances or lovers (à la Gary Wilson) and torchlight at the drive-in, in a synthesis as arresting as it is original. Even on the rare occasions when the lyrics waver toward a more stereotypical sensibility — holding on to ghosts, standing only for love, war in one’s heart (war itself is also a central thematic) — the music, along with Mercer’s intonation, carries them; and then our expectations are confounded as his stories twist away from a scene that seemed to promise some hint of familiarity.

Indeed, if I have any complaint, it’s that the vocals are sometimes buried too deep in the mix for Mercer’s words to emerge from a background of somber synths, heavy beats, and electronic dissonance, with guitar work that ranges from blues influences to hints of Subcontinental traditions. Again, we encounter echoes of puja, of devotion, and the religious gothic apparent not only in the abovementioned Old Testament references, but in familiar Orientalist images — conjured up on the part of the listener, rather than Mercer — of Kali, the Black One, or Shiva as Destroyer of Worlds. But, given our knowledge that the last has referred also, in the technological era, to a blowing-up, our ultimate finitude shouldn’t constrain the claim that Fuck Death will blow your mind.

More about: Blackout Beach