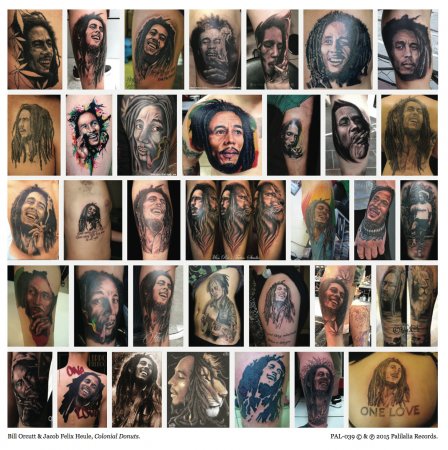

Fuck that shit. No, that shit. Like, dude, c’mon, where’s my bag of Doritos and Diet Pepsi? Like, for real, I’m about to lecture you on how the postmodern feeling of dread has nothing to do with the politics of the deli shop. I’m gonna get my guitar from its stand and a Budweiser out of that cooler there. Yeah, the blue one I bought at Wal-Mart a month ago. Yes, the one next to that Bob Marley poster and that stack of 90s Miami bass CDs that I bought when I went to the University of Miami to study how to be a Puerto Rican dancer. I’m kidding, you shithead. I love Puerto Ricans, don’t you remember Sasha? There are two types of Puerto Ricans, as far as I’m concerned: Florida ones and New York ones. The Florida ones smile more, are sexier, and eat healthier. The New York ones endure all kinds of culture clashes in the city, competing with Dominicans for the same gigs, getting mistaken for being Indian, and working in fast food, hospitals, or on the MTA; did I ever tell you about my Uncle Jose? He was an MTA driver for the 2 train and died from lung cancer: the whole family thought it was because he was underground so goddamn much. And my other uncle, Fidelio, he got hit by a car, fell on the wrong side of his back, and was done for. He used to play guitar, too. Not this one: this guitar was made from wood in Canada by a Frenchman. He used to play a guitar made in the Puerto Rican mountains, in that old jíbaro style, his chin a perfect square, his dimples waning, serenading in a rasp made of peppery suet. When I play the guitar, I don’t sing. I think. I think about Christopher Columbus. I think about the Taínos, now gone, an unwritten genocide. I think about how anyone — black, white, purple, red — can fuckin’ pick this thing up and start playing, just plucking, plucking away, plucking away at the strings until it’s good, all good, gone good, good like a porch with a beer and a dog and a fucking rifle on my lap. If anyone comes into this house I will bash their head in with my guitar, within reason. If Bob Marley came in, I’d have a talk. Why are you so famous? Why did you smoke so much weed? I know why he’s so famous, you shithead. But why the worship? Why the little Bob Marley shops on every little corner? Why on the birthday cakes? Why the tattoos?

I knew this guy, ha, I knew this guy at the University. Like, this dude was fucking white, from like Indiana or some shit. White as white cheddar, with Bob Marley tattoos everywhere. Sometimes I didn’t understand a fucking word he was saying; he tried to make his Midwest accent Jamaican. But it was a weird Jamaican, like “I-only-speak-this-accent-when-I-want-a-jerk-sandwich” accent. Fuck that guy! But his tattoos of Bob Marley intrigued me. One was a mashup of Mickey Mouse and Bob Marley. Another, The Grinch and Bob Marley. Another, Obama and Bob Marley. Another, Hendrix and Bob Marley. The last time I saw him on campus, he kept on talking to me about how he wanted to get Drake and Bob Marley on his pecs. He played guitar too, just like Bob Marley. But me? My guitar? Unlike Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates, you usually know what you’re going to get when I play my guitar. Thrashed-out swamp shit. Neo-hillbilly. Half-articulated fury. Phantom grunts. Zone farts. Frog burps. Sweat on steel. Mississippi River diarrhea. Fuckin’ noise. Just wanna make noise, love noise, make noise with my guitar, yeah noise, love noise, just wanna make noise, just wanna make noise because I am a fucking dude with a guitar, with a fuckin’ stack of guitar pedals, with oscillators and rhythm pulsators and fuckin’ fuck yeah! I wanna make some noise so I’m gonna make some noise! Fuck outta here; I’m here in the big city, I can make noise in my good ol’ American basement cuz fuck everyone else! Fuckin’ just wanna make noise, so much noise, at the dive bar with my black shirt on cuz noise, in the bakery having an existential crisis cuz noise, making a modular synth track cuz noise, fart in your face cuz noise. I’m Elmer Fudd up in this bitch. I’m that new John Fahey. I’m that John Fahey-John Cage hybrid. I’m that experimental Mr. Rogers. I’m that experimental Chet Atkins. All you haters know that I’m Barney with a guitar. I’m that neo-Jimi Hendrix reincarnated into old man dude. I’m Back To The Future I and II on my guitar, bitch. I’m going where Joe Satriani and Steve Vai could never go. I’m Ronald McDonald on my guitar, motherfucker; my riffs are made out of some powerful amounts of fat and sodium. I’m on some heart attack shit with my guitar, bud. My palilalia comes out in my fingertips, dude. So who are you? Did someone say your name? I labor on this thing, I cause enchantment. I play the blues, cuz it’s an American art form, and I am an American man.

You gotta think about these things through, seriously. The guitar is a colonizing agent. It exchanges cultures. One culture plays like this, another like that. You can be green and play like someone who is red, and does that make it any different? The guitar conquers. What culture is the culture of guitar noise? American? But can we go deeper? Can we say it’s actually the sound of a certain white American privilege? Or is it a great platform for a white American to critique that privilege? But then how do you do that without looking like you are celebrating something that you are actually critiquing? How? Noise music? What does noise music actually critique? Itself or some other agent? The guitar? Does guitar noise critique the inherent constraints that you have when you have a six-string tuned this way; and even if you don’t have six strings and you have four, you’re still in this constraint that is called musical harmony. OK, let’s get out of musical harmony, let’s get off that Bach and on our John Cage, let’s make sound, not music, and we’ll record it. But wait, is my heritage and gender inherent in how I play, and when does sound become noise? Does noise have a history, and is that history linear, and is that history most likely dominated by white males, men like Columbus? (Am I about to go back to high school, to my blue room, to that old time when the older kids in the neighborhood were listening to Blink-182 and I was on Hector Lavoe?)

Shit. These questions got me bugged. The material is the music, right? Timbre is the umami of music, and if that’s the case, the guitar is the salt of cooking. No, not the salt. More like garlic. Often used, but sometimes not. No, not garlic. Lard. Something that was often used and now isn’t so much anymore. The guitar was the 20th century’s greatest producer of culture. Now the computer is, because the guitar is “dead.” The computer is all kale, all microgreens, all gluten-free, Brooklyn, One Direction, Netflix and chill. Anyone who plays the guitar must be into zombies, into obscurity. Or at least zombie culture, zombie music, and necrocracies, like North Korea. What if Kim Jong-Un were to walk up to my porch and start playing covers of Bob Marley, sung in an impressive Jamaican patois mixed with a little North Korean slang? The guitar is the mediator. The guitar conquers all. The guitar is the conqueror. The conquistador. La guitarra. Maker of sound and maker of outer sound. Exchanger of cultures, dominator of cultures. A white thing, a black thing, a brown thing, a weird thing. Free jazz, brother. Punk, brother. No wave, brother. It’s all American, and the guitar saw it all. But now that the guitar is dead, and it’s all zombie music. Art music. Gallery music. White wall, loft, chair, Budweiser on the floor. Black shirt, jeans, barefoot. Look at me. I’m in the gallery. I’m in a critical state of mind. Anthologies surround me. Meanwhile the other world moves along to trap beats and Swedish-produced pop music, and I’ve got this thing in my hands that weighs 5 pounds, and I’m contemplating the world of mass media, tablets, and the English language. Open-form all the time, brother. Discographies that don’t lie. Collaborations, collaborations, fingers moving on strings. Does this ever get boring?

At some point, even outer sound can become a caricature of itself, just like at some point in life you need more structure than not. At some point, my fingers are enacting a reflex that is deeply embedded in the gray matter of my brain, out of a habit burnt up inside me. It’s just noise, bro, and if you know the template, you know the template. Dudes come out of their hobbit-holes and know it. This is the culture that they have when no other culture will accept them. Out of their holes, one by one. They like to freak out to this shit. Into this, this here noise. Into noise because it is material. Materiality. Composed of matter. Wood, strings, my body. And inside my body some of that Budweiser on the floor. That Budweiser gets into the music. So does my Chinese take out. So does the air of San Francisco. Onto the strings, into my voice, out through the recorders, into ears, into brains, into thoughts, into a memory, into an object on a shelf — the recording — decaying slowly on that shelf, on that wooden shelf, slowly and out of the way, out of mind, out of body, out of context, something hidden comes into the music, a hidden history, a hidden world, a secret garden, an abandoned palace. This is what happens. Work gets done. Alan Lomax out there in the fields with a bunch of prisoners in Texas, singing songs while lifting hay bales. An Egyptian in 2200 BCE tuning a harp in the shade of a pyramid. A bootlegger alive on the infinite plain of the Great American West singing a tune while staring into a fire, next to his horse. An English chambermaid looking across the muddy 19th-century tulip fields with a guitar in her hands, just fiddling with it. History, brother. This is history.

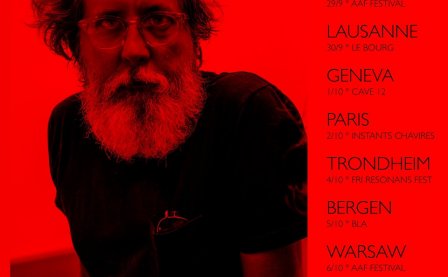

This dude and I, he plays drums, I play guitar, we critique history, we become history, we exchange languages, we get all wild and show people what sound can be. But we are a limit. Our instruments and our skin. We are white men, and that is a limit and a privilege. Some parts of the world won’t listen to our music, but that’s like any music. You can’t please them all: I learned that when I used to be a brunch cook. Certain people come out and see me play, and I expect them to be a certain way, to have certain tastes. They know my history. They know half of what to expect. I satisfy that, then push it by doing X, Y, and Z. But that’s it. My options expire at some point. I can pick up my electric and do some electric stuff like Dylan, but eventually my language expires. Like milk, brother. Even if my guitar is in a weird tune, even if it’s not even tuned, even if I’ve got a pedalboard, I’ve got these ten fingers and one brain and two eyes and that Budweiser on the floor, next to my shoes. It’s my limit. And I’m trying to make that limitation an elegantly chaotic sound. You know?

I’m done with my rant and need to fart. Ah, that feels better. Hand me another Budweiser, dude.

More about: Bill Orcutt, Bill Orcutt & Jacob Felix Heule, Bob Marley, Jacob Felix Heule