While many parallels have been drawn between Daniel Johnston and Brian Wilson, the comparison is only truly valid on the surface, chiefly in the struggle between balancing mental illness with musical genius. Deeper analysis, however, identifies profound differences between the two men and their work. For example, where hiatuses into seclusion (his bedroom) made Wilson lethargic and unprolific, such isolation allows Johnston to creatively thrive. Where Wilson required a lyrical foil to compose much of his best work (Tony Asher, Van Dyke Parks), Johnston does his best work alone. Where lush arrangements and production brought Wilson’s music to life, sparseness and bareness always defined Johnston’s masterpieces. But it’s in this last respect where the fundamental problem with his latest full-length offering, Is and Always Was, presents itself.

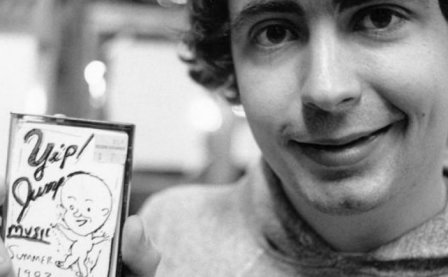

Like his acclaimed drawings, Johnston’s music was startling in its superhuman simplicity. Seldom did he use any adornment other than a single accompanying instrument, which ranged from acoustic guitar to piano to chord organ (and sometimes none at all). His vocals exuded childlike wanderlust and woe over their subject matter, whether it was unrequited love, fulfilled dreams, pet cows, jelly beans, King Kong, or Casper the Friendly Ghost. But in the late 90s, he started playing with garage-rockers Danny and the Nightmares, which with mixed results lent a thorny edge to his music, at different times drowning and bolstering his strength of voice. Then, in 2003, with Sparklehorse’s Mark Linkous producing, Johnston’s Fear Yourself, with its hazy instrumentation, represented a grand return to form.

Listening now to Is and Always Was, 48-year-old Johnston’s first full-length of exclusively new material in seven years, leaves the same impression as albums like Leonard Cohen’s I’m Your Man or Tiny Tim’s Resurrection, where brilliant songcraft and lyricism falter under incongruent production and arrangements: “Without You,” an otherwise bittersweet ditty about moving on, is almost entirely diluted by giddy piano and synth overdubs, while “Queenie the Doggie,” a sweet rumination on an ailing pet, moves awkwardly like half-hearted calypso. Indeed, too often here the childlike charm and heart-wracking honesty that exists in all of Johnston’s music is squandered amid such noodling.

The harsh truth makes itself clear: overdubs and studio pre-meditation trivialize Johnston's music. This has much to do with producer Jason Falkner, who has made a name both with his solo career and as a producer. Aside from the requisite piano and guitar by Johnston and drums by Joey Waronker (REM, Beck, Smashing Pumpkins), a lot of the music -- guitar, bass, and keyboards -- was performed by Falkner. Of course, you wouldn't expect a producer of his stature to embrace Johnston's early-day aesthetic, but it’s hard not to desire these songs in their sketchbook state, with tape hiss, zealous throbbing organ, and all.

Fortunately, Is and Always Was does have its affecting moments, in those rare moments when the soul of the music is adequately matched by its production. “Mind Movies” and “Tears” meander slowly, with Johnston’s vocal melody driving them; “I’m just a psycho trying to write a song,” he sadly declares in the former. These moments, while few and far between, signal the breadth of music that remains inside Johnston. It’s in this vein that, for all of its missteps, Is and Always Was seems less a career-defining shift and more a stop in one of music’s most fraught, enduring, and fascinating journeys.

1. Mind Movies

2. Fake Records of Rock and Roll

3. Queenie The Doggie

4. High Horse

5. Without You

6. I Had Lost My Mind

7. Freedom

8. Tears

9. Is And Always Was

10. Lost In My Infinite Memory

11. Light Of Day

More about: Daniel Johnston