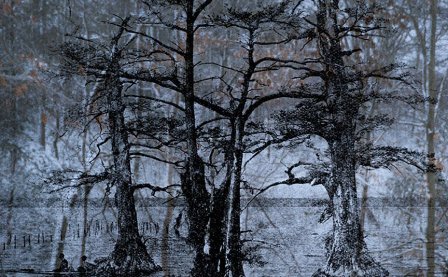

The sun smooth cresting over the ridge catches itself on a scintilla of something drifting about the air. Among stands of black pine and domineering spruce, glinting glimpses of floating figures organized by a primeval mountain geometry. The atmosphere is one of sanctuary. Planted in the friable loam like an acorn is a wisdom and a history. Twinned and twined, these two, crouched in the very dirt, await someone, anyone, to come and seek them out. A form of country magic. The Appalachians are old. It was, no doubt, the stately hunch of the mountains, the peculiar play of the sun, and the earthiness of the sky that sketched mandalas in the mind of John Fahey and demanded Henry Flynt to name himself autochthon. It is, no doubt, the alchemy of old earth that transformed rags into ragas.

Although a swamp boy by birth, Nathan Bowles — of the old-time stalwart Black Twig Pickers and moonshined drone ensemble Pelt — has a deep reverence for mountain soil. Perhaps a necessity for anyone who chooses to peddle in American folk traditions, Bowles has always been keenly aware of his place in tradition, not unlike fellow Virginian and NC transplant Daniel Bachman. Such a path has been well-trod and the thorns cleared long ago. We can trace lineages, if we are so inclined. Say, Mike Gangloff and Jack Rose into Fahey and Basho and Kottke into Charlie Patton and Blind Blake. However, what Bowles and our current generation of American revivalists have demonstrated is the clear vitality of this tradition, its powerful cling to our consciousness that requires we constantly revisit and reinvent it.

Even at its densest, Whole and Cloven, the third solo record for Bowles, sounds almost desultory, a great credit to his compositional approach. The feeling is not just one of a misty mountain ramble, but of a more connected, experiential movement, something secretly providential. Running his fingers along the banjo strings is the same as along the spines of library books. It is, at its core, an engagement with our shared cultural inventory, what we often reduce to the term Americana. Like the asik in love with the saz, the banjo has become a historical prosthesis, a method of extending oneself into the cultural memory. Playing the banjo and remaining cognizant of its history of rootedness and uprootedness is as much an act of channeling as it is invention. Whole and cloven, indeed. As we journey down this clear, well-trod mountain trail, Bowles stops and reminds us of the faults running alongside.

Resuscitating a long-lost gem is part of the work. Bowles always deploys his voice sparingly, and the only example of his strained, gutsy vocals is the cover of Jeffrey Cain’s “Moonshine is the Sunshine,” a litany of ludicrous folksy aphorisms and observations that perfectly justifies the archaeological attitude contemporary old-time sometimes must adopt. The bookending “Words Spoken Aloud” — sans voix, of course — and “Burnt Ends Rag” are the most typical, traditional-sounding fare, though excellently executed.

Where Bowles truly begins to stretch his composition, and instrument, is in “Blank Range.” A tempestuous charge on banjo made menacing by his low, droning voice is exhilarating from its start to its slow transition into “Hog Jank II.” The banjo swirls its notes together and breaks the eddying as soon as you can recognize the pattern. “Gadarene Fugue” with its biblical reference takes on a distinctly North African flavor, as it wends and winds through snakecharmer tones. The most discrepant piece is easily “Chiaroscuro,” a fluid solo piano exercise built on its internal contrasts. Its Riley-esque minimalism integrates another tradition into his work, further informing not only his composition, but also his concept of a complete and fractured culture.

Americana is a cultural inventory and, like all inventories, it requires the tireless work of two groups. The archivist, of course, to record and enshrine in our collective unconscious what we have made. Alan Lomax, being the archetypal American archivist, toured the US and UK with a recorder and attempted to preserve culture not merely as extensions of local histories, but local realities. Art is always local, of a place, resting quiet in mountain loam and bursting forth from people who till the soil.

The other group is composed of archaeologists, researchers to comb the archives and (re)discover, revive, and re-appropriate. They aim to make the old the new and to render porous the temporal barriers that alienate us from our own culture. Any indebtedness to Americana, which Whole and Cloven unabashedly bears, is a recognition of a place in history, a rejection of the supposedly sui generis, but not of innovation nor invention. Social, historical, political, cultural contexts are to be embraced and reformed simultaneously. This is what it means to create American art.

Nansemond, Bowles’s previous effort, was about place and history. Named after the Nansemond people, it depicts the land where their ancestors lived and the land they are currently trying to recover. You can go to Sleepy Lake in Suffolk, Virginia and perhaps find the same tire swing Bowles wrote about, just as you can stop by the general store in Chuckatuck. The main difference with Whole and Cloven is its scope, treating his instrument and the localities it occupies within the cultural archive as his meditative focus. The fault lines lay along the surface of his banjo and inside the cracks of voice. Whole and cloven, indeed.

Alongside a map and a photo, Nansemond’s insert carried a quote that applies just as aptly to his work here. A short selection from Sebald’s Austerlitz:

It does not seem to me… that we understand the laws governing the return of the past, but I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking according to the rules of a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like…

American old-time or American primitivism or however it is to be designated rests on this very notion, this compression of time into a single locus, a surrender to the power of our culture and our memory.

More about: Nathan Bowles