In 2012, Sia rose from the ashes of an indie career as a one-woman pop song factory, churning out hits for Rihanna and Britney Spears and Flo Rida. She wrote songs like “Wild Ones” and “Diamonds,” songs that cut like a scalpel, poke around a little, sew us up, and leave us alone forever. Sia’s pop hits didn’t distinguish themselves except in their brazen vacuousness, even relative to other pop hits. For Sia as a working artist, there was no longer an image to be concerned about; she needed only anticipate the desires of millions of consumers from behind the veil.

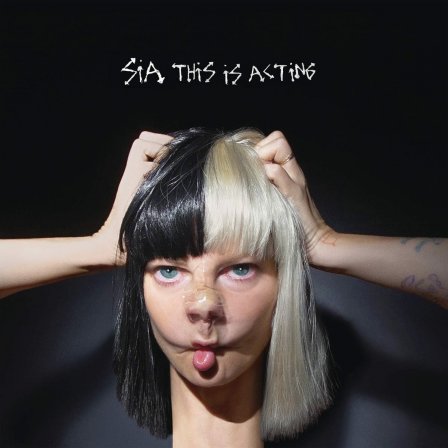

Because of the power and clarity of her own singing voice, Sia often sang the hooks herself on these hits, so it was natural that she progressed into restarting her own recording career. Out of the vacuousness she crafted a new image, embracing facelessness. She has done this literally by wearing her hair over her face like a mask, and figuratively by releasing music that acts as both mask and mirror, hiding her intentions and reflecting back our own. This is Acting, Sia’s second album following her pop star rebirth, is explicitly marketed as a collection of songs she wrote for other artists. We hear Sia acting: on a song intended for Rihanna, she’s woozy, sultry, and distracted; on a song for Adele, she slowly, painfully works the track up to its cathartic pinnacle.

Sia does what actors do, neutralizing herself so that you, your grandmother, the kid who picked on you in middle school, and your mail carrier all hear their own longings in her music. The songs on This is Acting are compact journeys from negative to positive, progressing with algorithmic precision from besieged (“Clipped wings, I was a broken thing/ Had a voice, had a voice, but I could not sing”) to liberated (“I sing for love, I sing for me/ I shout it out like a bird set free”). On most songs, Sia’s acting is passable: There’s “Move Your Body,” a banger written for Shakira, and “Reaper,” an upbeat, middle-of-the-road track for Rihanna, both of which almost come off as pastiching those artists’ styles rather than defining them. Other songs, like “One Million Bullets” or “Footprints” (inspired by that two-sets-of-footprints parable emblazoned on so many pieces of thrift store art), are generic and even asinine.

The truly effective songs are the ones that go after life and death. There’s a track about defiant self-definition (“Alive”), about spiritual rebirth through song (“Bird Set Free”), about loving someone so hard you incinerate yourself (“House on Fire”). These are songs for TV finales, songs that make you sing to yourself in the mirror, grasping at your heart, pulling your hair while beseeching God, “I don’t wanna die,” while somewhere, a 13-year-old kid is listening and doing the same thing.

This is acting. And if that seems to imply Sia’s not buying into all of this, well, it’s not the case. She doesn’t pretend to believe these songs communicate anything like insights — she’s said as much in interviews — but she clearly believes in the songs themselves. There’s simply no way she could hit the shattering high note in “Alive” if she didn’t. Actors actually cry when they perform; the fact that the tears are premeditated doesn’t make them less real. Like an actor, Sia instinctively knows how to tap into emotion in a way that’s almost utilitarian. “It really seems like the general public responds to songs about salvation or overcoming something, or that everything’s going to be OK, or that things are fun,” she told Rolling Stone. We are robots, and Sia has our access codes.

Of course, there are only so many times you can key into someone’s heart before they change the code, and after about 20 listens, the veneer crumbles a bit, and it’s a little too easy to see the gears turning underneath. But that’s not the most frustrating thing about the record; the most frustrating thing is that Sia has so much access to us and just doesn’t do much with it. She’s built an admirable persona that’s both mask and mirror — maybe next time she can show us something we don’t already know.

More about: Sia