I always gauge my uncle’s reaction to a new Wilco album. Uncle Dandridge, a longtime Wilco fan, reaching far back to when they weren’t even in existence — back to Uncle Tupelo, Belleville, Illinois glory — turned me onto the band. Tipsy accounts of why Tupelo were so splendid (a natural, zestful, unpretentious combination of influences) and stories of seeing J. Tweedy and J. Farrar perform at Maxwell’s in Hoboken; stories of running into Tweedy in New York City outside the Garden complex and swapping opinions of marriage (both had recently wed). I respect Uncle Dandridge’s opinion, regarding it highly — he’s a source with the complete context of the band’s career on tap. So, his reaction to Sky Blue Sky? He took a deep, relieving breath and proclaimed: “Thank God.”

You see, my Uncle Dandridge has always favored “straight-up” rock bands: The Replacements, Big Star, The Clash. He was big on that storied NATO phonetic alphabet release, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, enjoying the electronic bric-a-brac and studio dawdling (just as he had Combat Rock), but with A Ghost Is Born and the infamous 10-minute drone: “That’s a sign something’s wrong.”

It’s fair to say the more recent Wilco fans prefer the previous two albums — albums that are probably what attracted them in the first place, what with their deconstructive tendencies and decidedly “avant-garde” touches. These listeners mostly neglect early albums like A.M. and Being There, whereas the older fans revere them (rightfully). While the elders will rejoice in this sober, satisfied, and craftily subdued effort, the younglings of the bunch, with their abbreviated attention spans, iPod shuffles, and demand for instant gratification, will declare the album a boring and lethargic affair. (These are mere speculations, of course.) Advice to those listeners: Tweedy addresses them (“I’m going to need you to be patient with me.”)

Sky Blue Sky, with all its paleness and patience on the surface, is a slow rub. The music lathers the inner ear — thick — before absorbing, penetrating. It makes one vacant. Finally, its components fill the sinkhole at your center and reveal it as something both special and severe. Recorded in the cozy and homely Loft in Chicago, these musicians allowed songs to grow on their own, a sort of equal-opportunity nurturing process. This was comforting. Like Thomas Jefferson said in an 1813 speech, “The happiness of the domestic fireside is the first boon of Heaven.” Home is a focal point for this album, both in content and composition. Jeff Tweedy excavates the sorrows of domesticity or simply the longing for it. Chores (dirty dishes, tidying the house, changing sheets) and errands are as significant in the songwriter’s grand scheme as planet waves.

“It all began with a house,” Band biographer Barney Hoskyns wrote in rejected liner notes years ago. The Band and Wilco shuck similar cornstalks. On Stoll Road in West Saugerties, NY, The Band shared the casual philosophy of Socrates and put to tape whatever spouted from the ever-flowing spigot of bathtub gin. In a dank basement, there was Rick Danko and Robbie Robertson. Following the Hudson River upstate, you found Garth rolling the magnetic tape. Furnishing Big Pink, you had Levon Helm lugging a loveseat and Richard Manuel birthing vocalized ghosts.

Likewise, the impact of Nels Cline is apparent in the world that is Wilco. His guitar lines skedaddle and scamper across bridges and refrains, refraining from nothing. Glenn Kotche, with each piece of percussion like a prized possession, still stamps each song with his own unique mark. Stirratt, Mikael Jorgensen, and Pat Sansone make pinky-swear promises that every note matters; every chord change and suspension is a certitude. In the Loft, they are like family. They chuckle as they insult each other with jests. “You’ve got a head like a sieve.” “He keeps his wife like a doxy.” They cast old musical wives’ tales.

Tweedy has cleared himself from the fracas of prescription pills and the chaos of record label/big business balderdash. His voice isn’t as throaty as it’s been, his lyrics not as cryptic and juxtaposed. He speaks to you straight, with clarity. The focus is with the songs again. These are songs any carnival-goer could appreciate, though they are tough and require heedfulness. Tweedy is guided by a blissful ambivalence: “You and I will be undefeated by agreeing to disagree/ No one wins but the thieves/ So why side with anything?” he sings with a marvelous aching.

Some sort of Garth Hudson flannel-shirt funk infects “Shake It Off.” In other nooks, amplified static electricity and white noise are contained in something like a mason jar. On “Walken,” the jar nearly slides from the shelf and shatters to minuscule shards. The current Wilco band is a unit — their talents, a codpiece. They express content while pushing themselves toward quiet perfection, never allowing things to get too heady or inkhorn. They aim to please, but please themselves first and foremost, rather than finicky fans.

“What Light” speaks and sounds like a modest anthem of goodness and wholesomeness, much like Dylan’s “Forever Young.” Whether fans pan or take pleasure in Sky Blue Sky, it’s hard to argue with something such as this: “If you feel like singing a song/ And you want other people to sing along/ Then just sing what you feel/ Don’t let anyone say it’s wrong.”

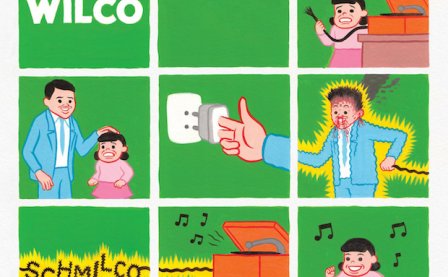

More about: Wilco