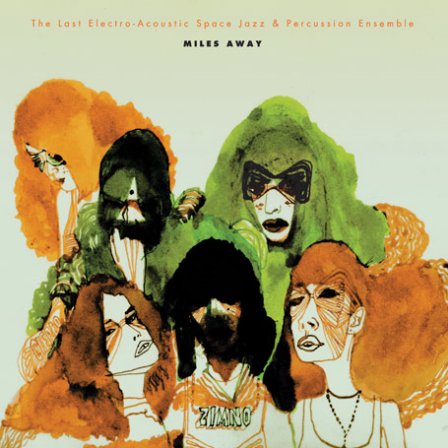

If you are new to Madlib’s densely populated and ever-expanding musical universe, you might as well start here. The Last Electro-Acoustic Space Jazz & Percussion Ensemble is relatively new and unexplored among the several alter-egos and side-projects that DJ/producer/emcee Madlib (aka Otis Jackson, Jr.) has developed over the years. He introduced this ensemble to the world alongside several other bands of his own invention on 2007’s Yesterdays Universe. Like most of them, this ensemble is actually a one-man show; it’s all Madlib, all the time. He’s been regularly issuing jazz-influenced albums like this since 2001’s Angles Without Edges, which was credited to Yesterdays New Quintet. That ‘group’ subsequently ‘broke up,’ and every ‘member’ went solo, releasing albums and LPs of ‘their’ own. It was confusing enough already, before Yesterdays Universe came along with its slew of new alternate identities and set the stage for a second cycle of exploratory side-projects. By that time, Madlib had already given us an LP from Sound Directions, and in 2008 he brought us Sujinho, an LP birthed from the Jackson Conti project: a lively collaboration between Madlib and Brazilian drummer/percussionist Ivan “Mamao” Conti. Miles Away is the latest development in Madlib’s musical world, but it’s best to think of it as an exploration of a persona that we’ve met before. He doesn’t reach for novelty here; he follows a train of thought, taking an existing sound and making it deeper and more expansive.

In one sense, this record is backward-looking, limiting itself to an instrumental palette that was laid out by a generation of musicians who were active over half a century ago. It has all the atmospheric haze and bottom-heavy soulfulness we’ve come to expect from Madlib, but Miles Away is unique in its single-minded dedication to a jazz idiom. While YNQ albums frequently wandered into groove and hip-hop territory, Miles Away spends most of its time with more conservative swing and Latin rhythms. On top of the drums and bass, the texture is made up of relatively basic stuff: vibes, pianos, and electric flutes, with a little sitar and organ. The grooves are spirited, loose-limbed, and free, but without ever falling apart or descending into cacophony. The drums have their moments of strife and rebellion, but nothing like the freakouts characteristic of something like the Monk Hughes & The Outer Realm project A Tribute To Brother Weldon. “Black Renaissance” pushes along with a matter-of-fact swagger, its musical statements divided between bass gestures and heavily accented piano chords. “Waltz For Woody” and “Two Stories for Dwight” arrive with an aggressive, forward-leaning swing, overlaid by half-attentive keyboard vamps and intermittent bursts of synth noodling.

Unsurprisingly, the songs on the album possess only a casual acquaintance with form, ranging from open-ended two-chord jam “The Trane and the Pharoah” to the loosely structured melody-driven exploration “Mystic Voyage.” Much of the album simmers like a stew, seamlessly melding sections and textures together without anything ever feeling separated from anything else. “Tones,” whose organ backgrounds slowly give way to a fiery battle between vibes and the drums, is unique in the scope of its dynamic development, but even there, if you’re not paying attention, you won’t notice it. There is a lot of creativity and energy going on in these pieces, but none of it fights for your attention. And like a good stew, nothing really jumps out from the texture or begs to be considered on its own merits.

Hip-hop has been “jazzy” before, and there are plenty of J Dilla-loving drumset players out there who bring their passion for hip-hop to jazz trios and quartets, but to have a hip-hop producer whose love for jazz goes so deep that he adopts it not just as a style but as a production method, not just as an influence but as a persona, is a rare and unique thing. It goes beyond mere surface imitation of the past; this is an example of true reverence. And reverence is one of the major themes of Miles Away, each piece being dedicated to one of Madlib’s musical influences. The names range from the well-known (Roy Ayers, John Coltrane) to the obscure (Horace Tapscott, Dwight Tribble). This type of thing happens in jazz all the time, with its seemingly infinite supply of tribute albums to Charlie Parker and Monk, its endless parade of Mingus and Duke Ellington revivals. But the strangest thing about it is that many of the musicians who are the most vocally reverent of strong personalities of the past are the ones who bring that same strength of personality to the present. This album feels as Madlib as anything Madlib has ever recorded, in spite of the fact that it operates within such specific limits and gives so much ground to the past. The Last Electro-Acoustic Space Jazz & Percussion Ensemble does not detract from the strength of Madlib’s creativity by multiplying his identity; it clarifies it.