Okay, I think I get it now. Jack White is not the “seventh son” or even the “third man,” but the “last man.” You know, the man who remains after all the wars have ended, and the class struggle has ended, and your band’s broken up, and your wife’s gone, and the money’s worthless, and there’s nothing left to do but hole up in your studio and make some noise. (See here.) Typically, the last man is a little doughy and kinda cracked. He has a lot of time on his hands and no sense of proportion. He collects. He archives. He welds. He has a kick-ass set of guitars and amps. He decorates his house with stuffed safari animals. He’s proud of his vintage scissor set, and he color-codes everything — towels, wires, walls, whole buildings, even people. And he plays the blues. “There aren’t that many things left that haven’t already been done,” says the last man, “especially with music.” And so he plays the blues as the music of last days, and plays them again, as if the world still counted on it. He plays the blues as they’ve best been played — compulsively, fretfully — with all the ghosts of the past on his trail and nothing but emptiness ahead.

On Blunderbuss, his latest and perhaps his greatest record, Jack White seems to be waking up to a whole world gone wrong. There’s blood on his face, but he doesn’t know where it came from. There’s a strange woman in his house, messing around in the fridge. He’s even missing a few pieces — hands, legs, shoulders — which makes it kinda hard to get out of bed. This might be only a hangover, but it also might be the apocalypse. And he himself could be anyone — John Gillis, Bob Dylan, Rip Van Winkle, or Rick Grimes. Either way, Jack’s gotta patch himself up and get back to work. The organ hums, the amp screeches into action, and he begins to burn it. As a whole, Blunderbuss is nothing if not the sound of a man firing up the van and delivering the goods. The first half blisters, the second soothes, and there’s not a single weak note or riff between them. “Every morning I deliver the news,” White sings on “Sixteen Saltines,” “Black hat, white shoes, and I’m red all over.” And even though you’ll recognize the dirty Detroit squall and the fierce banshee falsetto, White’s shtick is here embedded in a much larger story, the story of a man falling to pieces at the end of the world and finding himself again in sound. This is White’s great American novel. Think An American Tragedy or American Pastoral or The Sun Also Rises — White squarely faces the question of what makes a man in his time, and his answer is just as violent, grotesque, and perversely triumphant as anything in Dreiser, Roth, or Hemingway. “And I’m solo rowing on one side off the boat,” White screeches out at the end of “Sixteen Saltines,” “Looking out, throwing up, a lifesaver down my throat.”

In other words, even though Blunderbuss opens in anger and confusion, it proves a lifesaver, a pure pop fantasia, a nearly flawless example of Gram Parsons’ old dream of Cosmic America. You might be disappointed at first to find that White’s music is still seeped in the blues — blues structures, blues lyrics, and the whole blues ethos of troubled masculinity. But if, for the Stripes, the blues served as easy shorthand, a way of outlining a common set of feelings and circumstances, it stands here for a specific relation to history, an archival approach to being and time. Here, the blues is only a starting point, a way of stating the problem, and, ultimately, the emptiness of the blues form — its very deadness — becomes the freedom to roam and play. As last man, White’s got the sonic world at his fingertips; he skips from blues to prog rock to hip-hop to hayseed hokum to vibraphone exotica. Throughout, he wears his influences proudly. He knows his heroes, and he makes no bones about it. “Trash Tongue Talker” is a straight-up bit of Mick Jagger jive; “Poor Boy” — from its descending bass line to its aw-shucks vocals — takes you back to Muswell-era Kinks; and I’ll be damned if “Weep Themselves To Sleep” isn’t Sir Elton à la “Loves Lies Bleeding.” And then there’s “Freedom at 21,” which I can only describe as White’s own “Niggaz in Paris” — an avant-garde freak-out with a hip-hop rhythm section and a vocal track that jumps both beats and octaves on a dime. Given this genre-hopping genius, Blunderbuss seems less like a transition album and more like a late-era opus designed to show off White’s impeccable pedigree. Think White Album, Exile on Main Street, or Rattle and Hum. Think, of course, The Basement Tapes. This is the rag-and-bone work of a new-old last man on a mission: a little anxious, a little careless, out and out zany, but full of passion and urgency.

To be honest, I was dreading this album. The last two Stripes efforts were a bit stale, with Jack and Meg dabbling in pastiche at the sake of passion (“Conquest,” anyone?). Here, though, White seems at once troubled and energized by the breakup of his old band, not to mention his marriage. As Dylan did on Blood on the Tracks, he turns personal despair into grand mythology, and while the results are often ugly, they’re deeply felt and totally bracing. “Freedom At 21” lays it out plain; White’s nemesis here is woman as techno-modernist medusa. Over a seething shuffle beat, he snarls as much out of helplessness as of hate, “Two black gadgets in her hands/ All she thinks about/ No responsibility, no guilt, or morals/ Cloud her judgment… And she don’t care what kinda the things people used to do/ She don’t care that what she does has an effect on you/ She’s got freedom in the 21st century.” The last line’s the shit-kicker. White, a staunch defender of dead technologies, delivers it with both admiration and disdain, his misogyny laced with a much wider ambivalence about the modern world and its amoral progress. But this is only one side of the Blunderbuss mythology. The next track takes a more soulful approach. On “Love Interruption,” mighty Eros swaggers onto the scene, a sexy antidote to world gone stale, a violent break with time itself and a restoration of primitive being: “I want love to roll me over slowly/ Stick a knife inside me and twist it all around/ I want love to grab my fingers gently/ Slam them in a doorway/ Put my face into the ground/ I want love to murder my own Mother/ Take her off to somewhere, like hell or up above/ I want love to, change my friends to enemies/ Change my friends to enemies and show me how it’s all my fault.” And then the whole mythic assemblage shifts once more into ballad form with “Blunderbuss,” a gently sung tune of impossible escape and wordless love. Lyrically, I haven’t heard anything this effective in years; after outlining a baroque vision of Persian rugs and silver lockets, White’s lilting message strikes home like a lover’s sword: “You grabbed my arm and left with me but you were not allowed to/ You took me to a public place to quietly blend into/ Such a trick pretending not to be doing what you want to/ But seems like everybody does this every waking moment.”

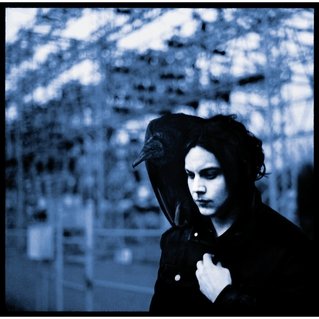

Ultimately, though, Blunderbuss is best defined by its humility, a light loser vibe that touches everything with grim laughter and excuses just about all of White’s obsessions and indulgences. In the end, the last man proves to be only a “poor boy,” a happy fool, skipping through the graveyard, trying to please his fans. Indeed, “Hip (Eponymous) Poor Boy” may be the best track on the album and perhaps the closest thing to an ars poetica for White. White likely stole the idea for the song from porch-mate and fellow po’ boy Bob Dylan, but his version is more buoyant, a grinning bit of vaudeville jive that wears its clowning on its sleeve. White’s pasty-faced poor boy gets into the game, provides a pill for the pain, and then ducks back out again, laughing all the way to the bank. With a bar-room piano pounding behind him, he sings, “Sometimes, a cold shiver comes over me / And it turns me on when the song takes over me/ But alright, I can’t fight if the odds are against me/ But I can’t sit still, because I know that I will.” White delivers the song’s refrain with a neat little vocal shiver, as if to imply that his whole career is shadowed by death. But this shiver is also a chuckle, a hoot, and Blunderbuss is best taken, above all else, as a graveside hootenanny. More than any Stripes record before it, the album revels in its own deathliness, its sheer pastness, but it also delivers something like an ethos, a sense of the past as enchantment, as survival and grace. Indeed, as White recently revealed, Blunderbuss emerged out of his preoccupation with death, and, in case we missed the point, he appears on the cover with a vulture on his shoulder and a power plant behind him. But that bird is nothing if not his familiar, a double for his own trickster soul, and that electric plant is precisely what powers up his gear. If this is the sound of death, I say play on, last man, play on.