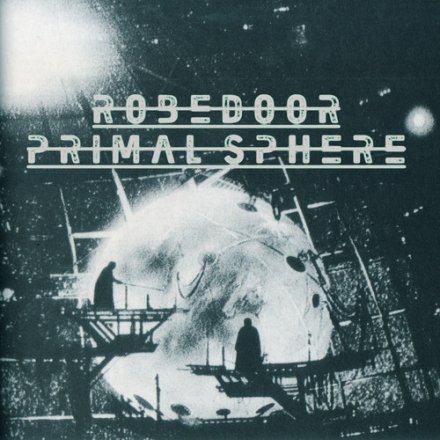

“Robedoor is more about alchemical escape, the world grinding above you while you stumble through some subterranean reality below.”

– Britt Brown of Robedoor

As with any record in the drone category, time plays a significant role in Primal Sphere’s exegesis. When trying to discover the elements that would make Robedoor’s new album “escapist,” I had to think about the qualities that would make any piece of media escapist. Whether it be literature, film, television, music, or some kind of hobby or sport, escapism’s primary role is to distort the perception of time by compressing it, making it seem as if I were reading for only 20 minutes rather than two hours. Generally, the opposite of this, the stretching of perceptual time, is accompanied by monotonous repetition. But here we have Britt Brown describing his music as a form of escape, even though its use of repetition is more conventionally related with tedium than enjoyment. So, what if this repetition were looked upon not as monotony, but as a visceral recapitulation of an imagined landscape, offering the listener a new plane of reality to occupy, one that is specifically internal and private?

Drone and noise music offers just such a plane. There are few things more neurotic and private than the making of and the listening to music like that of Robedoor. The slow movement and utter impotence of it creates a space for imagined possibilities, but only on that private, individualistic level. One carefully listens to small alterations in the melody, timing, or volume in order to expand their scope of the plane. Sounds are added — “filled in,” in a sense — by the mind. These can be based on past listens, current mood, and the listening environment. If Robedoor’s live shows attempt to occupy the entire space with the drone, then not only is the drone supposed to be occupying the entire mind, but also the experience of the surrounding space as the sounds compress or expand depending on the environment’s shape and size. It gives a physical connection to some objective reality on the outside while paradoxically creating a new reality for the mind to occupy internally.

[Visit full site to view media]

Robedoor’s brand of drone comes laden with heavy, driving bass lines; primitive, distorted vocals; and relentlessly recapitulated melodies. Since Robedoor is no longer utilizing the talents of M. Geddes Gengras, who took with him the live drums and also a good deal of musical intelligence, the duo has turned to simple electronic drum beats. This return to basic machinery sees them steering away from the more doom metal and even blues elements of Too Down To Die and into the more foreboding industrial noise that unfolds on Primal Sphere. The feeling of a consistent forward movement, like the movement of some sadistic assembly line, pervades each track, but somehow this movement never reaches any goal. It’s instead steeped in bitter stagnancy, like a band of men marching off to some unknown war, hoping for glory but never given the opportunity to prove themselves on the battlefield.

Like any other drone-noise, Primal Sphere relies on repeating melodic themes that vie for authority in the mix, as each song builds its sonic landscape. It has a surprising consistency and polished cohesion that separates it from much of Robedoor’s early, more heavily improvised work. The extremely tight and, as Alex Brown himself describes it, utilitarian “Stagnant Venom” sets the stage well for what will become a tense affair, filled with the illusion of progression, yet offering little in the way of release. The second track, “Blasted Orb,” has whiffs of a 1980s horror film soundtrack, though one where the villain is perpetually giving chase and the future victims have no hope of escape. All of these building rhythms and movements are engaging, though the lack of more improvisational elements gives the record a coldness. Rather than detracting from the heightened sense of apathetic urgency, the coldness in fact highlights it; the songs, built out of improv sessions, turn into grinding epics that set their own pace that the artists must then follow.

Maybe such a paradox — between a physical, objective reality and an imagined one — is the crux of the issue, finding the space so overwhelmed by the brute force of the music and its repetition that there becomes only one place habitable: an imagined realm in the mind’s eye. Which brings us back to the discussion of escapism. When one uses media as an escape, it’s presumably because there is a harshness to the outside reality overwhelming enough that one seeks to explore other possible realms. It also seems that, to be called true escapism, the experience should be a cathartic one in order for reality to seem more manageable when it must be engaged with again. Primal Sphere offers only half of this experience: allowing the listener to escape to the mind, but, because if its unresolved tension, does not provide the opportunity for catharsis; listeners are able to escape from their dull reality for a moment, before being brought back to reality with an even greater sense of the impotency of their own hubristic notions of progress. If this was the final goal of Robedoor’s newest release, they have an album to be proud of.