A Short Essay On Have You In My Wilderness

The issue is the possibility of love, as Avivah Zornberg begins

her recent book Bewilderments on wilderness

and the accompanying wandering,

the lonely wandering,

of people in search of their desire.

Desire is polyphonic,

as Lacan knew,

independence encircling independence,

drifting amidst,

a framework in which things fit

and don’t.

In this respect,

love songs are always a convergence

of form and content.

I wish I could scribble notes in the margins of songs.

Listening, I wander in my own wilderness,

and I want to drag my finger

through sand and water

and write my way back—

Late last night, I was listening

to “Betsy On The Roof.”

As I walked, a cat scrambled

to avoid me. But it stopped,

opened its mouth,

fell to the sidewalk,

stood up and rubbed

against me.

It’s a question of territory, of whose is whose.

The cat watched me as I walked away,

curiously,

under a streetlight.

Have You In My Wilderness is all about

walking away

and looking back,

the content of desire and its form,

the voice in search of clarifying itself,

The way, when we climb a mountain,

Stevens wrote,

Vermont throws itself together.

Everyone with whom I’ve talked

about this album has drawn —

in their own way —

the same conclusion:

But I don’t want to conclude just yet.

So allow me some words on citations

and annotations.

Citations, as you’ve seen this far,

are a crutch. But crutches

serve a useful function:

balance, above all, but

also a transfer of power

to another body,

polyphonic legs to aide

in our wandering.

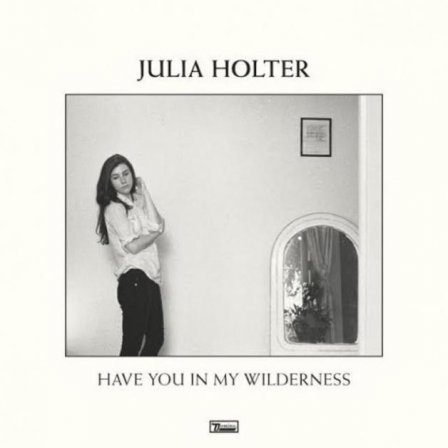

Julia Holter has been best known for who she cites,

perhaps to the detriment of the reception

of her art.

Good writers are good readers,

but the reverse isn’t necessarily true:

and as a writer, I’ve struggled both

to hear and to write beyond

points of reference.

Yet, in this bewildered album,

the citations are buried.

Perhaps, for the first time,

for the most part,

the song that she is singing

is her own.

Can you hear the difference

voices make,

unaccompanied?

Which brings me to annotations —

and then I’ll conclude —

and to a memory I have of a book

by Roni Horn, Another Water,

another voice in the wilderness,

and how I think it makes sense

of what I’m hearing, here.

Throughout are photos of the River Thames.

Points of water are numbered,

and running along the bottom of the page

are annotations, like (405)

“You walk, and the river runs…”

“…one thing leads to another and another

and another.”

Perhaps the most intriguing thing

about Holter’s wilderness

is how the songs themselves

wander through it.

The ocean stands as a central metaphor.

Night, too.

But it’s as simple, no,

yes, as the unfolding of desire.

It’s the subversion of the tyranny

of the pop song and the aural manifestation

of desire’s drift,

or trudge,

wherever it goes.

In the background, throughout, her voice

annotates,

in stunning polyphony,

like Horn’s watery associations,

the unknowable trajectory

that each song always already

takes.

If the result must be quantified here,

so be it,

but I keep listening, and I’m still surprised

by what I hear,

where I go,

and how it is

that I manage to end up there.