When Chris Forsyth talks about studying with Richard Lloyd, the guitarist and founding member of Television, he talks about learning “grammar.” Forsyth was still in the foundational stage of his own guitar playing in the days when he would meet Lloyd in Midtown for a lesson before heading to his day job at a cafe. Lloyd’s lessons are known for their focus on the hard math of how music works: the ratios, the sequences, the proportions. But for Forsyth, it apparently felt linguistic, too, as if he’d been watching conversations going on around him — like the rambling-junkie exchanges between Lloyd and Tom Verlaine on Marquee Moon — and was finally learning how to chime in.

Forsyth himself emerged later as a member of Peeesseye, the Brooklyn experimental group noted primarily for free-jazz carnage and bursts of shattering noise. Peeesseye’s best material, though, is their most minimalist work, driven by an exploration of the density and durability of different textures. Peesseye dissolved in 2011, but Forsyth’s work as a solo guitarist, including 2013’s Solar Motel and his collaborations with Brooklyn drone composer Koen Holtkamp, have been inspired by the same kind of minimalist approach. He leads his band in building brutalist edifices of sound, girded by repetition, and then driving each piece to their breaking point.

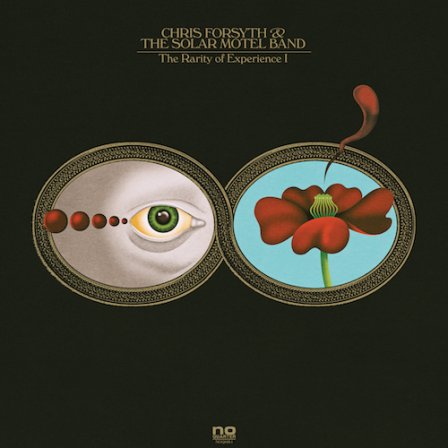

The Rarity of Experience is a double album divided into two distinct halves, titled The Rarity of Experience I and The Rarity of Experience II, that by turns maintain Forsyth’s architectural approach, with the addition of a few more conventionally “song”-like pieces and add a few more corrosive effects to it. The cluster of rock songs that make up the first half of the album are the most identifiably influenced by the likes of Television and Lou Reed’s 1980s band with Robert Quine, anchored by Forsyth’s guitar, its tone rich and thin like a gold sheet. These sounds trigger all kinds of sense memories, especially when Forsyth and keyboardist Shawn E. Hansen lock in tight: you see a wet, steaming New York street, taste the cheap coffee at a Midtown diner. It’s late-nite music, with menace hanging over it like fog. (Forsyth sings a bit on these pieces, too — an admirable if unnecessary exercise for a musician whose clear strength is speaking through his guitar.)

Try listening to “The First Ten Minutes of Cocksucker Blues” synced up with the first 10 minutes of Cocksucker Blues, the lost documentary chronicling The Rolling Stones’ 1972 American tour. Forsyth’s band sets off with a heartbeat thump; the film’s aloof black-and-white gaze settles on Mick Jagger’s cock, swaddled in white briefs; Keith Richards’ face, which looks hollow, hardened, as if it were notched out of clay; the blaring stage lights, which the camera can’t stop flicking over to. As the film’s narrative starts to congeal, Forsyth’s piece destabilizes, descending first into a “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’”-like acid trip jam featuring congas and sax and then stretching out into noise. As one work steps from daze and into coherence, the other lapses into the primordial: a mangling of grammar, a fuck-you to narrative.

“High Castle Rock” is the last track on The Rarity of Experience I, splitting the difference between the structured pieces at the beginning of the album and the spaciousness of the music that follows (including “First Ten Minutes”). “High Castle” never loosens up the way “First Ten Minutes” does; instead, it drives single-mindedly toward satisfaction. The piece begins with the interchange of rock riffs, one stacked upon the next. In a typical rock & roll tune, these riff-driven grooves would lead toward verses, bridges, soaring choruses. Here, we just get more riffs, piled on evenly like bricks. Drummer Steven Urgo’s rhythms move spider-like, forward and sidelong at once.

Then, after five or so minutes of minimalist rock jamming, the drama of the piece is activated by Forsyth’s guitar, beating and fluttering, the flag on top of this structure. The band drives back again and again to this high point throughout the duration of the song, a marathon of tension and release, a musical parallel to spiritual or sexual climax. Forsyth said achieving this kind of immediacy was one of his main concerns while making the album. “In the world that we live in now,” he told Aquarium Drunkard, “everything is so mediated and going through so many different lenses, that actually having a direct experience with something, the rarity of that seems really profound to me.” These climactic moments of “High Castle,” and the others like it on the record, are a kind of triumph of Forsyth’s musical grammar, too: the efficiency of communication, the transmission of feeling via the blunt physicality of sound.