Ecology includes all of the ways that we imagine how we live together. Ecology is profoundly about coexistence. Existence is always coexistence. I share this thought with Timothy Morton. Kōhei Amada and Sugai Ken share sentiments as they distinctly twist and interpret traditional Japanese folk concepts and sounds in “Shinshunfu”.

The full album title refers to the Kyōgokuryū school of koto, founded in 1901 by Koson Suzuki. As Takuya Kitamura explains in his excellent and informative liner notes for this release:

It was a new form of koto music born out of the move to create a ‘national music’, which arose during the Meiji era with the influence of Western culture, and also the increasingly active kairyō shōka (improvement songs) movement. It preceded the shin-nihon ongaku (new Japanese music) movement led by Michio Miyagi (1894-1956) and his contemporaries to modernize koto and traditional Japanese music.

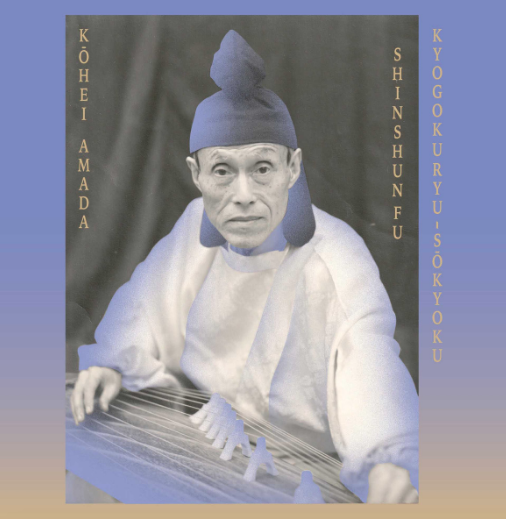

With Kyōgokuryū, Suzuki higlighted the koto as a solo rather than an ensemble instrument and often sung lyrical poetry to accompany his playing. This singer-songwriter approach represented quite a radical shift in koto playing, an attitude that was taken up by Suzuki’s disciple and the second leader of Kyōgokuryū, Amada. While this playing method became popular among hobbyists, Kyōgokuryū was never accepted as its own school of koto. So, it is special to think about the way that this recording represents a rare piece of 20th century Japanese experimentation, as well as a particular folk history.

In 1970, Amada (1892-1985) made an offering with a piece called “Shinshunfu.” The two-part composition was originally written around January 1956 and this recording first appeared on the 1970 LP Fukui-ken mukei bunkazai shitei, Kyōgokuryū-sōkyokushū, dai-issyū (Fukui Prefecture intangible cultural property, Kyōgokuryū-sōkyoku collection, vol. 1).

Spencer Doran describes it as “a more recognizable duet between koto and Irish harp, and…an elongated vocal piece repellent with droning shō and taiko drum bass hits.” The presence of the Irish harp threw me off a bit at first, but Kitamura explains that, after a bout of international travel, Amada was the first artist to bring Irish harp music to Japan, and it was his inclinations towards experimentation that solidified him as a koto master after Suzuki’s passing.

When I sit with Amada’s work, my immediate experience of time begins to move at a Shinshunfuian pace. I realize I don’t really understand time or how it moves, but I do understand that the sun rises and falls, and that seasons change. Branches of green wood bend their backs in moss and rain. This very Earthly experience of time has defined innumerable poems and tales across centuries all over the world, and, when listening, it is interesting to understand that I am listening to a story even via instruments, vocal arrangements, and so many other contexts unknown and previously unheard of to me.

Kitamura supports this thought when he writes:

This neoclassical reconciliation of ‘all times and all places’ came to fruition in “Shinshunfu”, which linked back to the kugo and ancient times through the medium of Amada’s Irish harp. At the same time it should be noted that, through traditional koto music, Amada incorporated Western music and instruments into the gagaku [Japanese court music] mode pieces that he composed, performed and sang.

And, Amada’s lyrics are as follows:

At the beginning of a New Year

Iridescent clouds flow far away

The morning sun shines, illuminating everything around

The sea is calm as far as the eye can see

Many people are happy and prosperous

The sea and mountains are overflowing with happiness

We receive this blessing

Let us praise the symbol of the ancient Gods

In celebrating the beauty of nature

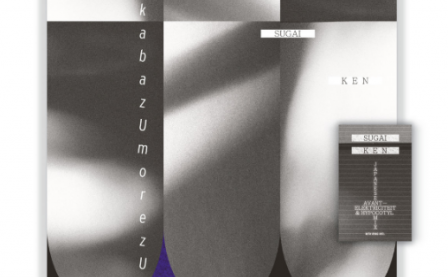

Doran also illuminates how Sugai Ken’s remix takes the piece in a “non-deterministic, GRM-like meta-concrète direction…jump-cutting in high definition between synthetic birdsong, haunted vocoded voice and arresting, back-of-the-head foley.” (Read the rest of his notes here.)

Ken’s interpretation skews away from these more historicized narrative tones and crafts a site-specific plot that invites one to muse on sound as a particular, in this case digital, manifestation rather than an aid to storytelling. Where time with Amada seems to flow, Ken tinkers with it to such a degree that I’m launched into an understanding of time as material rather than experience; a material and an experience.

Osaka’s excellent EM Records will be releasing this collaboration on 10” vinyl and CD formats in March. Listen further and preorder by clicking through the audio player.

More about: Kōhei Amada, Sugai Ken