We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

“I can hear everything. It’s everything time.”

Here we are, floundering at the tail end of the decade, grasping to make sense of the last 10 years, when that ancient quote (actually from Gang Gang Dance in 2011) had already provided this decade’s temporal framework for what feeling and existing might look like this decade. This quote, this foundational assumption, presaged this decade’s perceptual and material eruptions of sounds, of images, of ideas, of bodies; reducing our grandiose theories into beautiful yet fairytale simulations of purity and vanity — into rain and glitter. It was a statement, but also a warning, heralding — perhaps even willing into existence — what was to come: a decade both explosive and incomprehensible. It was everything time, and we could barely handle it.

Time, this decade, figured as much into our writing as words themselves — even when we didn’t realize it — and the same could be said of its music. Many of our early favorites this decade, from James Ferraro to Ariel Pink to Oneohtrix Point Never, would effectively swap traditional notions of musicality and engage directly with phenomena like nostalgia, cultural memory, and the corresponding junk left behind. No longer just a simple, comprehensible repository for things that happened, the past became part of the exclusive present, because distinguishing between the two increasingly felt like what time eventually does to the differences between 3rd and 4th grade, or what increased distance does to rocks and pebbles. Our past was not just aestheticized for apolitical nostalgia, ironic indulgence, or mindless repetition; the past was restaged, reperceptualized as a disruption in our listening, calling into question our entrenched, vestigial expectations concerning “originality” and taste. The results were sensually provocative and perverse, sometimes even confoundingly rote, but it infected the entire decade, offering dynamic, multilayered ways to not only subvert our temporal orientation, but also explore how affect itself could challenge our assumptions about resistance under capitalism.

And indeed, most of our favorites this decade didn’t hinge on signaling their politics. (Didn’t need them to either. We have plenty of ways to know when we’re getting fucked.) From vaporwave’s radical appropriations and Kanye’s destructive provocations to PC Music’s wild HD pop experimentation and Dean Blunt’s drifting, ephemeral gestures, this decade’s most controversial musics — at least the ones we cared most about here — were not marked by political upheaval or rupture, but by ambivalence and ambiguity, even uncertainty. This decade, it was OK to not know whether you “liked” something or understood what was “meant.” It was OK to not be able to envision a future because our depictions were always-already anachronistically displaced. It was OK to not force yourself to choose between celebration or rejection, because our art’s value was in perpetual oscillation. Music, here, was quickly dematerialized, reterritorialized, and re-coded for algorithmic consumption (18+), collapsing and folding into itself (E+E), stumbling into bizarre juxtapositions (DJ Rashad), calling attention to the medium itself (D/P/I), and vomiting brilliant recombinations (Klein). This restaging of aesthetics happened almost instantaneously (Lil B), sometimes accidentally (Farrah Abraham), and oftentimes originating from and rapidly reproduced by quick-witted, meme-savvy teens who had no reason or incentive to explain themselves.

So, yes, sometimes it was about having faith in the creative output. But other times, it was about having faith in selves. In this decade, it was okay to cry, to embrace our E•MO•TIONS, to vamp on our mercuriality. In this decade, death was real. Representational and symbolic exchange is always subservient to material transformations, and some of our favorites offered quite devastating ways to mourn, from Carrie & Lowell to A Crow Looked At Me. Still others deepened how we relate to our bodies, uncovering new materialities and new compositions (Elysia Crampton), exploding our “normative biopolitical imperatives” (SOPHIE) and “demanding transmutation” (Arca). We witnessed this shift in many of the artists on this list, and some of us underwent (and are currently undergoing) this shift ourselves. And yet we were constantly reminded that our bodies, while forever expressive, were also forever exploited. They were trapped in “corrupted relations that exist between postcodes” (Babyfather), hopelessly tethered to the “elaborate wretchedness of humankind” (Scott Walker). Who-we-are was in conflict with what-we-do, and the ambient technologies that enabled much of our communication this decade provided exactly the kinds of platforms that would encourage not civic participation, but data generation. Before we knew it, “taking a chance” meant adding a new brand of deodorant to our shopping cart. Welcome to the future?

If the correlate of a past that’s endlessly reproduced is a future that never manifests, perhaps imagined futures simply lost their critical role and had become junk themselves. Perhaps they were simply cultural artifacts rendered meaningless through a technological materialism that offered both sensory replenishment and heightened temporal awareness. The future, just as with the past, was not immune to the aestheticization process, as shown in our decade’s obsession with futurity. But sometimes all it is is scope — rocks and pebbles. Because if we zoom out — from the days to the months to the years, to the decade and beyond — what we find in the chase for that elusive wholeness, that unifying element, is that the thing that gets you to the thing has always been another thing. Music, for us, was one of those things. We often framed it with theory, but we felt it as desire, and it dripped from our ears, like nectar. A sweet, sticky, golden everything. While music articulated the complexity of our feelings this decade, changing us from the inside until our insides were inside-out, it also reminded us of a simple yet paralyzing tragedy of personhood: the moment we’re always waiting for is likely a replica of one we’ve already felt — and may never feel again.

This is what time does. It eventually renders even our most obsessive desires moot, as we move from crisis (financial) to crisis (ecological) to crisis (individual). Everything is fleeting. But unlike the first decade of TMT’s existence, in which it was often marked by privileged discernment, “intellectual” curation, and faith in the noisy subversion of capital (look how that turned out), this decade we strove for disunity, telepresence, and multiple perspectives: how our lack of consensus made room for possibility; how we embraced trends and transition in a time of sensory abundance; how fluid identities could emerge through syncretism, hybridization, and bottom-up subacculturation; how we practiced embodiment to tell cute stories about affect, movement, and sensation; how nuance offered passageways to our own materiality; how our music provided counternarratives and problematized notions of truth; how noise was no longer our noise (but was actually our noise all along); how we found in our music semblances of healing and palliative care in response to some exhausting, though not unprecedented, years.

We all know how those later years felt at home, under the covers, anxiety draining our souls, but those very same years felt different while clicking around on the web. Time plays differently here. In virtual worlds like Second Life, time has no immediate aesthetic effect: nothing crumbles, nothing washes away with time. Even if all of the avatars staged a mass exodus, it remains preserved forever in its eerily pristine, uncanny state until intervention, whether it’s a code update, through technological obsolescence, or actual physical disconnection of its servers. In our world, here at Tiny Mix Tapes, time shows itself in our digital ruins, manifesting as technological breakdown and incompatibility: broken images and incorrectly rendered text, conflicting coding languages and unreadable characters, dilapidated streaming embeds and exhausted hyperlinks pointing to a musician who may or may not have ever existed. It’s long since happened to early versions of the site, going back to our Geocities days in 2001, and we can already witness this process happening even in the posts we published this decade. The digital deterioration is real, and it’s both haunting and beautiful: the former because our identities become threatened by a past that eats away at itself, and the latter because the deterioration will eventually create space (physical, emotional, virtual) for something new and different.

This is something to celebrate. This is what we want (even if it’s fake). TMT wasn’t made to be projected into the future, nor was it made to be a forever lasting anything anywhere. That’s what plastic’s for, and there is beauty in letting go. Who knows what the next decade will bring, but as this one comes to its anticlimactic close, bringing us no closer to truly understanding our world but perhaps closer to accepting and embracing our eventual deterioration, the truth is, we don’t even have to think about music anymore. Words are just words that you soon forget (Laurel Halo), and while we all do stuff, sometimes stuff does itself (PC Music). If our most prolific artists (Lil B, Dean Blunt) taught us anything about excess in a supposed age of specialized, niche-driven taste — a marketer’s paradise, by the way — it was that we’re all really just amateurs, winging it. We love theory and criticism, but they alone won’t save us from anything. All we can say with confidence is that, past the cultural explosion and incoherency of this decade, through the blurriness of everything-time and its spectral hold on how we perceive the world, we here at TMT feel overwhelming gratitude: for the time we spent together as a scrappy yet passionate family of “writers,” and for the time we spent sharing with you, “the readers.”

Sincere thanks to all of you out there. We are eternally grateful that anyone anywhere was willing to join us in this experiment in criticism and music writing. <3

To close out the year, we are sharing our Favorite 100 Music Releases of the Decade. It was compiled from individual lists by current writers and some former, with minimal intervention. To prevent every single Dean Blunt release from occupying a spot on the list, we imposed a limit of two releases per moniker. So, yes, this means that many favorites are missing (find some of those here, here, and here). We apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused.

100

John Maus

We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves

[Ribbon/Upset The Rhythm; 2011]

Find a free text-to-speech. Copy this blurb into it, pick the homie “Charles” (he has the best voice), and press play. Now, close your eyes and listen. Envision a Lazy River that would top a Travel Channel “best of.” Now immerse yourself in it. The water temperature sits in that sweet spot between “little more than lukewarm” and “first step into the shower” — the Maus Zone. Can you feel it? Let the river flow through you in its unique, tantalizing ways — it has an innate fluidity that could both kickstart a party with friends and cause you to cry driving alone on the Florida Turnpike. Now imagine nearby innertubes playing analogue synth and spoken word tapes of Alain Badiou until slightly deflated, and then listen for a piercing guitar lick here and a synth wail there. This is the music of the Maus Zone, and at the turn of the millennium, this completely ecstatic, life-affirming sound expressed itself as We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves. It was, and still is, worth every moment.

99

Kara-Lis Coverdale

Grafts

[Boomkat Editions; 2017]

In recorded music, there is always an end. We’re keenly aware of it, and that expectation of a conclusion, of a piece ending, is integral to how we experience music. But on Grafts, Kara Lis-Coverdale used some type of magic that we couldn’t quite explain. Every time we listened, it was as if we had entered a timeless vacuum. There was nothing around, except a moving, glittering display of heavenly lights splayed all around, lapsing over each other like waves. It was like the packaging was gone. Rather than feeling anxiety over its impending end, we felt in control, as if we could stay in “2c,” “Flutter,” and “Moments In Love” forever. But, despite the poignancy of Coverdale’s spell, the music didn’t go on forever. We could always go back and stare at the lights as long as we were around — and we often did — but there was indeed an end. There is always an end.

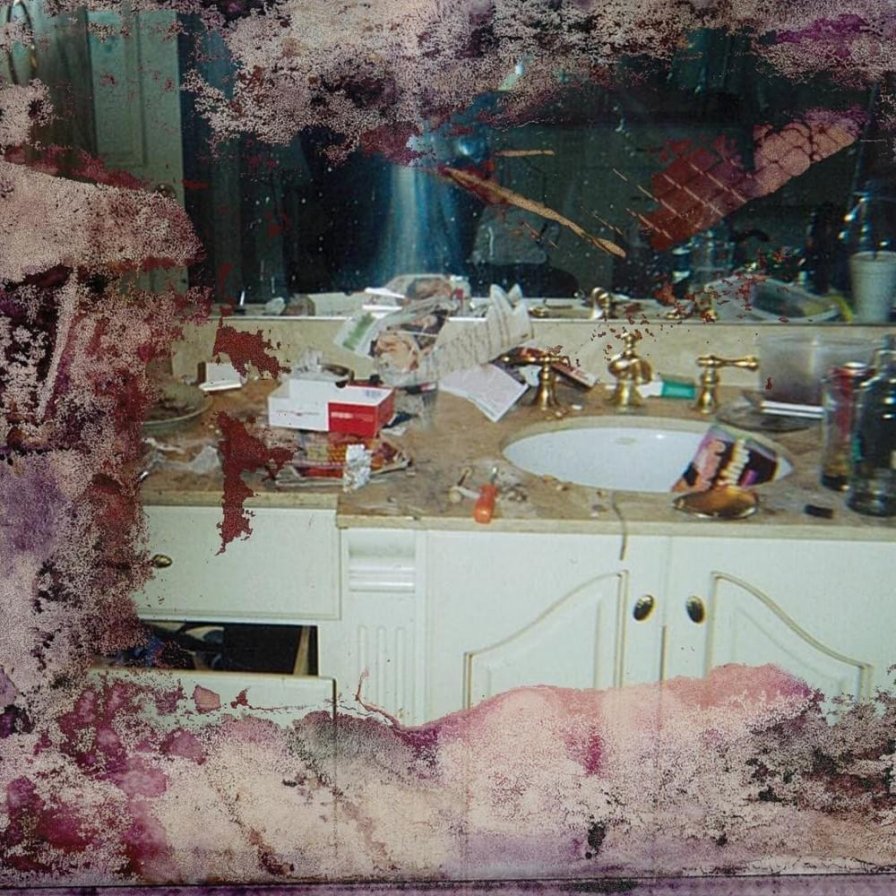

98

Pusha T

DAYTONA

[G.O.O.D. Music/Def Jam; 2018]

Pusha T’s DAYTONA served a perfect course and deserved a star from the tire people. What was not to like? Pusha’s calligraphic, unmistakable flow; a chef with a savory cut in rare supply. Kanye’s taste in suppliers, his attention to detail on every beat. The love for the material, the proportions; it all mattered. Every bite worth taking. Each piece a scrap of soul worth more than its weight in gold. A life told in layers — the tarnish, the beauty, the new material between. Hold still and sense his history. Organic poetry. Hot sauce and tennis balls. Life baked in. Ye rang out. Reduced, condensed. Perfect timing, perfect amount of heat. Stopping just short of too spicy. Haute suite. Look, there’s obviously still gonna be some things that only T gets to know. But it went deeper than that. You can’t teach it, you know? DAYTONA, this little thing. Can I have some more?

97

Deerhunter

Halcyon Digest

[4AD; 2010]

Here we are, nearly a decade down the road from the release of Halcyon Digest, and the album has littered my personal memory databank with traces of its 11 marvelous tracks. Miming along to the saxophone parts on “Coronado” while standing on the lawn of my decrepit college house. Soaking in the isolated stillness of “Sailing” to accompany feeling like my heart had been punted across New England. Closing my eyes in Webster Hall and being lifted to the sky as “Helicopter” folded over itself and exploded in inevitable breathtaking fashion. Honestly, it feels quite fitting, as Halcyon Digest was itself an album of memories, hazy recollections of past lives both real and imaginary. It was pictures and words and designs, cut out of old magazines and rearranged into something new. Cover versions of Golden Oldies that never existed. It was hearing “Desire Lines” for the 60th-odd time and wondering yet again if one day it would be physically possible for humans to live inside of a song. Something fleeting and ephemeral etching itself into permanence.

96

Bill Orcutt

A History of Every One

[Editions Mego; 2013]

Guitarists will sometimes warm up by hitting their strings a little before starting to play. For composer and interpreter extraordinaire Bill Orcutt, sometimes hitting is playing. Indeed, there were sequences on A History of Every One that were downright barbaric on first listen. As soon as Orcutt’s treatment of the trade union morale-booster “Solidarity Forever” started, it was obvious that we were in for a one-of-a-kind slab of magic. But with traditional spirituals standing next to festive fretworkouts and minstrel and work songs marching alongside two Oscar-winning Disney ditties, there was a different sort of fairytale glitter going on here. A History of Every One was still a lovely piece of lunacy, however, and despite many moments of extreme strain and disorder, the album had a sweeping, strange beauty that has been making our heads swim since its release in 2013. Far from being a time capsule, the album pointed a way forward in free expression, and everything worked. Containing a dozen tours de force, each one indistinguishable from its most common — or most deformed — version, A History of Every One was a let-it-bleed collision of energies that is still one of the more “alive” guitar experiments you’ll likely ever hear.

95

Beyoncé

Lemonade

[Parkwood/Columbia; 2016]

Where Beyoncé established Beyoncé as a brand, Lemonade positioned said brand as a mode of performance art. Knowles-Carter had already turned her releases into unannounced audio-visual events with her self-titled 2013 album, but with Lemonade, the pop icon’s not-so-private personal life and changing relationship to American and global media consumption seemed inextricable from the project’s genesis, distribution, and reception. Released exclusively on the artist’s own streaming service, accompanied by a 65-minute film on HBO, the album’s tracks played like 2016’s feminist response to Here, My Dear, preceding the #MeToo movement just as Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance of “Formation” (the album’s lead single turned bonus cut) preceded the NFL’s identity crisis, the latest terms of which are now being negotiated by none other than Beyoncé’s husband. Considered alongside 2017’s 4:44 and 2018’s Everything Is Love, the album also kicked off a trilogy of brilliantly transcendent, if also tellingly misunderstood, sociopolitical treatises from the Knowles-Carter family. Perhaps most importantly, though, Lemonade was the decade’s most ambitious break-up-to-make-up album, one for life partners to argue over and embrace together like no other. Who knows? If C Monster saw it premiere with Savannah, maybe it’d be his favorite Beyoncé album, too.

94

Zs

New Slaves

[The Social Registry; 2010]

New Slaves hit me hard in the chest and never left. Every song was a law, a sculpture of raw energy, a spectacular commodity. Twisted and beautiful, wrought from astounding performances and inspired studio magic, New Slaves is still revelatory 10 years on. It was in 2010, at my (and Jonathan Dean’s) beloved campus station, when I first heard “Gentleman Amateur,” which instantly hooked me on the group. And it was also in 2010 when Tiny Mix Tapes ruptured itself and gave New Slaves the #1 slot in its year-end rankings, which is also the moment I realized that this site knew what the fuck was up and I needed to write here. But 10 years on, I still can’t adequately explain how amazing this record is. I can barely even explain how it sounds. “Unique chamber music compositions using rock instruments, microtonalities, and extreme textures that never underestimate their audience or compromise on execution.” “Noisy, raw, gorgeous, difficult, caustic, cleansing, numbing; a slowly exploding beautiful art bomb.” Something along those lines, but better. I would want to assign a specific turn of phrase to it, to coin something unique to describe this stunning record’s idiosyncratic noise vision. But the best music is always hard to explain. That’s what makes it so: the impossible things it conveys that can’t be captured in language. The things it fantasizes aloud, the new fantasies it creates in turn. There’s proof of something here, something we haven’t figured out yet, buried deep in the chaos. Some new model for living, adapting, and surviving. With it comes this strange optimism, that the harsh rigors of the reality you find yourself in can be worn, like armor — the proud decorum of a future corpse.

93

Bill Callahan

Apocalypse

[Drag City; 2011]

I share a space with Bill Callahan. It’s not a small space, it’s a city. We see the same sights over and over again — violet-drenched sunsets, eternal grids of highway chrome, the crystalline owl peering above the Austin skyline. The same grocery stores and gas stations and the DMV. Existing day-to-day in a space like this, the wondrous and the mundane begin melting together, smearing like the mountain landscape of Apocalypse’s cover. Bill Callahan’s masterpiece resides within that smear, coming across as both grounded and unknowable. Our home country, which contains our home city, which contains our home structures (physical, social, interpersonal), is viewed bleary-eyed from Australia, its avatars a legendary talk show host, four legendary country singers, and a small sampling of our atrocities, not legendary but sickeningly real. By the record’s end, Callahan has denounced the life that so consumed him a half hour of album-time prior, settling into a gentle ride and ultimately becoming the road itself. Has he finally become something so ethereal and beyond himself that he exists only as part of the landscape itself? Absolutely not. His final words on Apocalypse: “DC 450.” It’s the album’s catalog number, reminding you that this is an album, a finite work of art that, brilliant as it may be, simply exists.

92

Actress

R.I.P

[Honest Jon’s; 2012]

In a time when time ran backwards (2012, to be precise), rising soccer star turned archeologist Darren Cunningham excavated fragments of recordings from a time after human extinction. Caked with lime, richly warped and discolored by mold and decay, haunted by chrominance signal ghosting effects as well as actual ghosts, these artifacts had nonetheless survived, on the whole, in an acceptable state of preservation. It was determined they were/will be created by AI military think tanks in a style that exhibited vestiges of 21st-century rap and house and suggested a corollary interest in the by-then obsolete concept of “Dance.” The think tanks were/will be specifically mandated to reverse-engineer and weaponize the concept of “emotion,” and their inability to grasp anything but its surface manifestations, combined with the organic processes of reverse time and reverse soil and a software-driven sense of intellectual longing, created its own unique textural poignancy that found its way into unexplored human neuro-pathways, arousing actual emotion amongst the final generations (in forward time) of homo sapiens to survive on planet Earth.

91

David Bowie

Blackstar

[Columbia; 2016]

Blackstar was recorded in secret and released two days before David Bowie died from liver cancer. Bowie knew this was going to happen, but we didn’t. I’m interested in those two days. Now, we can’t separate these events from one another, Blackstar and David Bowie’s death, but there were 48 hours where the album was just another new project from an aging rocker. As we look back on Blackstar, there’s a strange way in which Bowie lives beyond his death more than some others who die, because he’s rooted so deeply in this object. He affects us from it, and so he doesn’t seem truly gone. A highlight of the 2010s and one of Bowie’s most powerful records, this album continues to remind us that the things that unfold in this world change the way we see artworks. The dark grooves of the prescient “Lazarus,” the devastating new meaning of “I Can’t Give Everything Away,” the frenetic cadence and the mysterious sci-fi frame of the title track. What were those two days like for people who were listening, before this album became what it is now?

90

Jenny Hval

Blood Bitch

[Sacred Bones; 2016]

Jenny Hval spent the first half of the decade putting words under a microscope with lyrics that were at once blunt and razor sharp, where music (or sometimes just sound) grew organically from her confident yet deadpan delivery. While Blood Bitch was a culmination of that process, it was also a turning point. Hval’s self-examination expanded to an exploration of identity stretching time, space, gender, and myth, delivered with a newfound sonic warmth (“Female Vampire”), vocal tenderness (“Period Piece”), and lyrical vulnerability (“Conceptual Romance”). But in a decade where heel-turns to pop music came to feel like a cynically predictable career strategy for experimental artists, few on either end of that spectrum took the kind of risks Hval threw herself into. The gasping, out-of-breath pulse running through “In The Red,” the screamed panic of “The Plague,” the whispered dream diary of “Untamed Region,” and even the candid question “What’s this album about Jenny!?” blurted out right in the middle revealed an artist able to make her music more challenging and spiritually probing than ever, all while embracing pop music on her terms. Blood Bitch was one of the most open-hearted albums of its era, even — or especially — when it was dripping with blood.

89

infinite body

carve out the face of my god

[Post Present Medium; 2010]

At the turn of the decade, harsh noise expat Kyle Parker sighed ambient tracks of relief more suitable for avoidance than integration, going away than getting along. As the self receded into absence, “Dive’s” slow fade in of granular chordal melds resonated with coarse serenity inside the curved bowl of an empty skull. Moving his carapace through symphonic mandala (“A Fool Persists”), trailing expoflora (“Drive Dreams Away”), and marine life (the title track), Los Angeles-based Parker looped and steered his exhausted orchestra-of-one in an aftermath of fraught nerves. Embedded in the collection of post-escapist sustainments, beacon track “Sunshine” blinked ChipCorder-esque throbs across an overcast outstretch of dull haze and polymeric shimmer. Spatial and substantial, linear and circular, Carve Out The Face Of My God die-cut hollowed-out residue from hallowed music into flatlines that reflected the nihilism in the divine, and vice versa.

88

The Knife

Shaking the Habitual

[Mute; 2013]

Before we get too deep into this, I feel this obvious detail deserves recognition: Shaking the Habitual, as a title, was dead-on. I mean, even beyond its cheeky referencing of Foucault. Sure, Karin Dreijer Andersson and Olof Dreijer were committed to “[shaking] up habitual ways of working and thinking… [of re-evaluating] rules and institutions,” all that good post-structuralist shit, but what really made it resonate like The Concern for Truth never could was how truly SHOOK it left us all. This thing was so fucking monsterous, it famously broke our scoring system. I once listened to it very loudly and in its entirety on a plane; somewhere around “Crake,” I thought there was a real possibility that we were going down (what with all that clanking), but I vividly remember being way too unconcerned about it. Shaking the Habitual’s genius was that it riled you up — about gender stereotypes or fracking or boring sex or whatever — but it never killed your mood. There was a dreadful irony here that music like this could, through its physicality alone, relinquish our grip on our privileges, our violent habits, our possessions, that these sick beats and synth squelches could “end succession” if only more people would hear it. The Knife were bent on “failing more” though, but not before they succeeded in completely dismantling everyone’s expectations. Maybe this is where it starts though: with a flurry of wooden clicks and breathy chirps and rapturous screeches, like cracks in a dam holding back hoarded wealth, like an unshakeable urge in the left foot of a billionaire who’s never danced. In all honesty though, thinking about kicking capitalist habits is hard, but when this shit is on, I’m ready to lose. Bring it on.

87

Amen Dunes

Through Donkey Jaw

[Sacred Bones; 2011]

For Damon McMahon, the transformation from Mark Tucker to T. Storm Hunter occurred sometime during recording “Jill.” The manic, fragmented psy-fi of its locus: a discombobulating melody that bounced across every surface, sounding like a stalled Bataszew. It was the beginning of a disconnect from D.I.A., but it was also the mutagen that further separated himself from an outsized beginning. McMahon once lamented that he hoped Through Donkey Jaw would be hated, because he thought it wasn’t quite as sincere as his future recording output would be. But here we stand, and Through Donkey Jaw might be McMahon’s most sincere output. The range of emotions were uncontrollable. McMahon ripped his old formula to shreds, disassembling it one song at a time until the record ended in a scrapheap of teary-eyed confessionals. The road McMahon has taken since has been lengthy, but each subsequent release has recalled Through Donkey Jaw’s imitable spirit in some way. And as he’s polished his ride to a fine sheen, he hasn’t buffed out the well-worn scratches or picked at the rust. McMahon has never been able to shake his confessional tune, never abandoning his own version of Tucker’s 1964 Cadillac. In fact, unlike his predecessor, he’s come to own it as the reliable, if beat up, mode of transport is was built to be.

86

Rich Gang

Tha Tour Pt. 1

[Cash Money; 2014]

Obviously, we don’t accept the term “mumble rap” as a meaningful genre descriptor: Listening to this towering mixtape collaboration between Atlanta innovators Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan does not entail any of the strain implied by perceiving spoken words beneath the friction of mumbling. It’s instead a pure thrill to revisit Young Thug’s exuberant leaps in pitch, his tangled, unpredictable flows, his syllables flung like Jackson Pollock drips. And though less influential, Rich Homie Quan is a gripping stylist, too, his drawl smeared, dipping in volume, marked by inventive dynamics and repetition. The mixtape was a lexicon of ear-worms. Every song was memorable, and yet our ears were able to pinpoint new phrases with each spin. We listened while availing ourselves of the crowdsourced transcriptions on Genius, comparing what we heard with the majority opinion. We listened by firing up old hard drives of leaked MP3s or prying open the browser window of DatPiff. (This mixtape is still not available on major streaming services.) Even though the term “mumble rap” still sucks, listening to Tha Tour Pt. 1 made us reconsider the term as a reminder of the way Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan helped us hear, in all audible language, the eruption of melody out of speech.

85

Helen

The Original Faces

[Kranky; 2015]

There’s a scene early in the 1989 film Weekend at Bernie’s in which star Andrew McCarthy attempts to extract his boom box from an impressive amount of tar built up on a steamy NYC rooftop. This imagery — a boom box encased in muck — is an apt metaphor for the sounds produced on Helen’s 2015 album, The Original Faces. Liz Harris (Grouper, Nivhek) was joined here by pals Jed Bindeman and Scott Simmons (with backing vocals by the mysterious “Helen”) for a 12-song missive of what might be referred to as “surf noise,” if classifying such things is important to you. Beginning with the pleasantly noodling “Ryder” and ending with the short-but-sweet title track, the group burned through 33 minutes’ worth of sonic downer bliss; even the songs lasting south of two minutes left an indelible mark. But despite its relative brevity, the music was catchy and dense enough that you’d find yourself discovering new sounds deep in the mix, like diving through a new cereal box for the prize buried at the bottom. The Original Faces was the type of album that socked you in the stomach for your lunch money then tripped on its way out the door, a roaring yet surprisingly tender addition to Harris’s distinctly overachieving and achingly gorgeous oeuvre.

84

D/P/I

Fresh Roses

[CHANCEIMAG.es; 2013]

Microseconds into the opening pitch-shifted warble of “In Dreams” — wait a minute, is that Roy Orbison? — I knew there was something special about Fresh Roses. Alex Gray’s D/P/I project always had a sort of capacity for serrated incision, an ability to recombine the sonic lost & found into a thrumming beat or a collage or an open-source cave painting that pointed 13 different directions at once. But there was something so crystalline about Fresh Roses’s vision. It sprawled from the towering centerpiece of “DEPRESSION SESSION,” a piece wherein we were cast about by the (de)motivation of a TED talk’s angry older brother while hard drives went senescent in the periphery. Country songs melted, beats were cheese-grated: WAKE THE BODY BACK UP! Forgive me, but in the last 10 years, so much that was SUPPOSED TO BE SOFT went hard as rock. What stage of post-irony are we in again? Who’s in charge here? I can’t remember cuz I deleted most of the note on my phone where I was keeping track. All it says now is “Fresh Roses.”

83

Andy Stott

Luxury Problems

[Modern Love; 2012]

Andy Stott has had his finger right on the pulse this entire decade, but Luxury Problems in particular continues to hit just as hard as it did in 2012. Shortly before its release, after years of balancing his techno output with a day job at Mercedes, Stott quit the luxury car business. The change deconstructed the rhythm of his life, day bleeding into night and back into day, as if time belonged to another existence. And that was the sound of Luxury Problems — techno that lost all sense of urgency, all sense of compulsion. Techno that techno’d to techno, for no one and nothing. And yet it was so alive, like the beating of some dark, dank heart powering the underworld and, indeed, the one above ground, too. Still, the most we could do was feel its heat; we knew it was there, but we couldn’t know it in itself, separated as it was by an impenetrable and unknowable mass. To get lost in non-time was the ultimate luxury problem, and the record took us right into it, enveloping us in a peculiarly woozy sludge that we willingly got ourselves stuck in. It was a beautiful, even inviting, sludge, thanks to Stott’s old piano teacher Alison Skidmore, whose layered, decaying choral vocals were otherworldly and perfect for Stott’s compositions. The collaboration was fruitful in a way that Stott could not have imagined when he reached out to her. I mean, they hadn’t seen each other in 15 years! Go ahead and call your old piano teacher. Try to make something as good as Luxury Problems.

82

EMA

Past Life Martyred Saints

[Souterrain Transmissions; 2011]

The first song on Past Life Martyred Saints ended with Erika M. Anderson declaring “Great grandmother lived on the prairie/ Nothin and nothin and nothin and nothin/ I got the same feelin inside of me/ Nothin’ and nothing and nothing and nothing.” Was it emptiness that Anderson felt? A lack of agency in a world where her role was sharply delimited by forces outside of her? Or did we detect something productive in this emptiness, something of the pioneer spirit of her ancestor that suggested limitless possibility? The ambiguity that characterized these lines permeated the record as a whole. The imperative “Momma’s in the bedroom, don’t you stop” from “Breakfast” could have been either the breathless command of a young lover or something infinitely darker. Her lament on “Marked” that “I wish that every time he touched me left a mark” could have signified either romantic yearning or a desire for evidence of the damage inflicted upon her. It was from this muddiness, this imprecision, that the album gained its potency. What broke our hearts was Anderson’s willing recognition that you don’t stop loving the things that try to kill you, even when you know you should.

81

Freddie Gibbs & Madlib

Piñata

[Madlib Invazion; 2014]

The recording of Piñata began as an unlikely collaboration between two artists on divergent paths: Madlib had established himself as a producer of such diverse talents that he set himself the task of releasing an album a month throughout 2010 and pulled it off; meanwhile, Freddie Gibbs had garnered hype as a rising rapper, was snatched up by a major label, and just as quickly became a casualty of the game, languishing in relative obscurity during the three years it took to record the album. Gibbs’s situation was so dire that he recorded his vocals while literally living on the streets and fired them back to Madlib, who summoned his crate-digging magic to create an album that weaved thug rap braggadocio with eccentric soul samples. With guest spots from established legends (Raekwon) and artists who would go on to define the decade (Earl Sweatshirt, Danny Brown), Piñata was a classic as soon as it hit record stores (they were still a thing back in 2014, if you’ll recall). The ultimate proof of the record’s status was the ongoing trajectory of Gibbs and Madlib: by the time they reunited in 2019 for the sequel Bandana, it felt like a victory lap from two legends in their own right.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series