100 Flowers is a roots-level view of the of the contemporary Chinese musical underground. The aim of this column is to articulate the contingencies of the Chinese scene and arrive at a parallax view of Chinese society from the perspective of its most peripheral negotiators. Read the previous entry here, and email the author here.

“To speak of ‘experimentation’ in China means to discuss it literally: Every single person in the entire country experiments daily and tries out new things. This is particularly true of the last decade. In pre-Olympic Beijing any street, building, restaurant, store, company or regulation could be transformed or even disappear at any given moment. The Nike advertising slogan ‘Everything Is Possible’ reflects the spirit of these times.”

So writes Yan Jun, the de facto godfather of Chinese experimental music. In Beijing, he is often referred to honorifically as Yan Laoban or Yan Laoshi: boss, teacher. This quote is from the insert of milestone 2008 4CD comp Anthology of Chinese Experimental Music 1992-2008, released on Sub Rosa in the same year Beijing hosted the Olympic games and symbolically stepped up to prime position on the international stage. After detailing the strange genesis of the Chinese musical avant-garde via randomly imported Western influences, naive experimentation, and the kind of outsider art practice that could only develop within the context of China’s historic authoritarian rigidity suddenly ceding to a new era of capitalistic flexibility, Yan concludes: “Westerners deconstruct their own traditions in order to redefine them, whereas the Chinese simultaneously attempt to understand the Western tradition and to rediscover their own. While Westerners believe that the Chinese are re-inventing sounds that already exist, the Chinese believe that they are simply re-inventing themselves.”

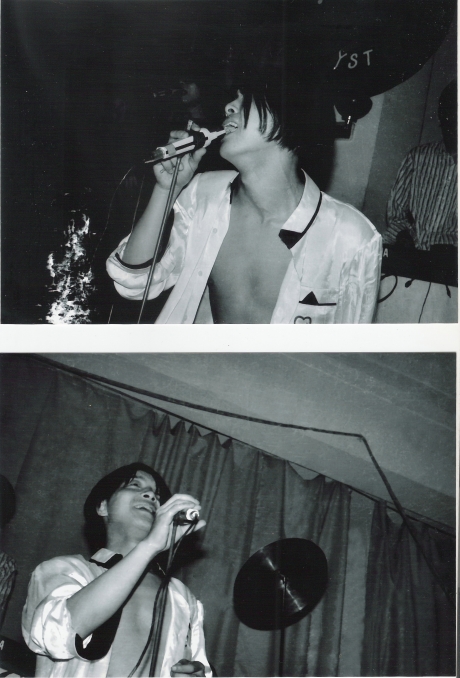

Yan Jun grabbing the mic at a Lanzhou dancehall

Yan grew up in Lanzhou, capital of China’s northwestern Gansu Province. As a college student there in the early 1990s, he was among the first generation of youth poised to seize upon China’s new attitude of economic openness, best encapsulated by then-regnant Deng Xiaoping’s apocryphal edict: “To get rich is glorious.” While his classmates scrambled to heed these words, Yan followed a natural predilection toward more strange and perverse cultural forms, which at the time took extreme dedication to find. He bonded with his mother’s colleague’s son over a shared interest in Beijing metal bands Black Panther and Tang Dynasty, who by then had broken through to become among the first Chinese rock bands to achieve national exposure. From this connection, he met students in his university’s music department who spent their evenings playing in metal cover bands at local dancehalls with 2元(~$0.30) covers.

Yan initially engaged with music via his first passion: writing. An aspiring poet and student of literature, Yan treated his first months in Lanzhou’s underground music scene as an assignment: “I decided to write a report. I spent one month to meet them, to meet all these new kinds of human beings. All this underground life. The music was very poor. The scene… most of them just copied Cui Jian and Black Panther.” He quickly developed a rough classification scheme grading the quality of various Lanzhou bands. At the top was Decay (残响), a Tang Dynasty cover band who won respect for their serviceable renditions of the latter’s hyper-technical, pentatonic riffs. Decay became Yan’s best friends, along with fellow show-goer and Lanzhou’s resident avant-garde music pioneer, Wang Fan.

Wang Fan’s first public performance, alongside his job as a dancehall singer, March 1993

Yan published his first “report” in the Lanzhou Radio/TV Newspaper — a local rag printing showtime schedules — in 1993. After that, he fielded offers for freelance jobs reviewing rock albums, but given his non-linear thinking and the growing importance of underground music in his daily life, these “reviews,” more often than not, took the form of romantic poems. By the mid-1990s, the standard bearer of Chinese music journalism was the Beijing publication Music Life (音乐生活), which focused on “new music.” (This catch-all term included jazz, electronic music, and other Western forms, but was mainly employed because the government forbade any publication explicitly focused on rock ‘n’ roll.) Yan avidly followed the work of Music Life staffer Hao Fang, the first Chinese journalist to write seriously about techno and noise music and the first to introduce Nirvana to the Chinese scene on a wide scale via his 1997 biography of Kurt Cobain. Inspired by the idea that he could write about anything, Yan submitted a 16-page article to Music Life with the hope it would be read by an ex-girlfriend, who had moved to Beijing, and his hometown friend Wang Fan, whom by 1996 had begun home recording with prepared guitars, household objects, and found television sounds, and whom also had relocated to the capital.

Da Kou, Dancehalls, Discovery

Yan Jun’s 16-page tome — a meta-narrative cobbled together from reviews of anything he could find in Lanzhou, including local releases, obscure Swedish metal bootlegs, and Mazzy Star cover CDs — was well received at Music Life. Actually, it was partially received. “Page 7 or 8 was lost,” recounts Yan, “so the editor split it into two articles and published them both.” He soon got more offers. He found a random gig contributing to a State-subsidized industrial technology newspaper with an anomalous two-page music spread in each issue. The paper’s editors had no point of reference for the subject matter, leaving Yan and his colleagues complete freedom. “We used nicknames, pen names. If you collected all the pen names you could find a poem. We just picked anything we liked, wrote about any music, nobody knew… There were several times we wrote about music that didn’t actually exist.”

Yan’s anarchic sensibility naturally led him to contribute to Punk Generation (朋克时代), a short-lived publication founded by a Guangzhou businessman and edited by early rock writer Yang Bo. In the effectively pre-internet environment of late-1990s China, Punk Generation provided a powerful national platform for disaffected youth to voice their grievances with mainstream society, to profess their membership in a shared subculture, and to place this subculture in historical context with punk, electronic, and industrial music movements from across the world.

Punk Generation Vol. 2 cover and inside spread featuring No’s Zuoxiao Zuzhou

Although people like Yan were constantly pushing the boundaries of what could be considered acceptable as music, and although his tastes rapidly outpaced local bands, the subculture he belonged to was populated by a single mythic figure: the rocker. “In the mid-90s, the first generation of experimental musicians, no exception, everyone was [a] rocker,” Yan Jun says. “Anyone who was not in the underground rock scene… getting drunk… probably belonged to the boring, materialistic part of society… All the earliest experimental, noise, electronica, and free-improvisation musicians originated from this scene. It was a dejected, rebellious scene searching for a radical, and very loud, mode of expression.”

In mid-1990s Lanzhou, Yan Jun and his friends appropriated apathy, ennui, and rock ‘n’ roll as tools of radical rejection. The first widely distributed Western music in China was country music in the John Denver mold. “In the 90s, there was also Enya. Ohhh, everybody listened to Enya. And Yanni. [Starting] from this country music, you can draw a line to New Age.” From there, Yan Jun built up his musical vocabulary by picking up the most extreme releases he could find, progressing from his first two purchases, a Queen Greatest Hits cassette and New Jersey by Bon Jovi, to random discs from Godflesh and John Zorn. These were not official imports but rather da kou, surplus stock from Western labels smuggled into China and sold illicitly, marred by a vertical gash intended to prevent resale.

For Yan and his friends, da kou became the bedrock of social life. A new cassette purchase was enough to prompt a party, a long night of drinking, even a cross-country trip. “Each city had a small underground club, maybe two or three or four different groups of people… I knew one guy, a fan of Slayer. He lived in another city… Just to listen to one Slayer cassette, he traveled [950 miles] from his city to Lanzhou. When we met, we drank and we listened to music and we guessed, ‘Who’s this band? You win, I drink.’ This music was very important in this small community.”

Aside from sitting around each other’s apartments listening to the latest da kou haul, the options were limited. Various local dancehalls had a “disco hour” from 9 to 10 PM that would feature music heavier than the normal rotation of saccharine Mandarin pop. Yan’s circle frequented Seahorse Club, a bar carpeted with cigarette butts, bottle caps, and other accumulated filth. Yan’s band friends worked there and would play thrash metal and Tang Dynasty after “disco hour,” sometimes broadcasting their own songs and Wang Fan’s hard rock experiments if they could get away with it.

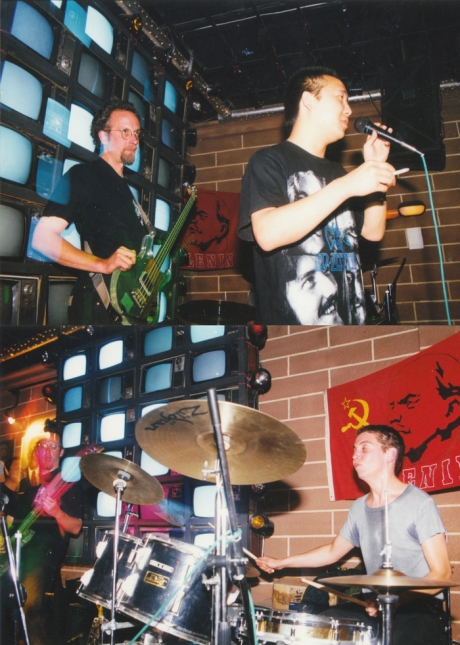

Decay performance at Seahorse Club, 1994

There were virtually no bars explicitly dedicated to live music. The earliest was a small dive called Double Hundred whose stage consisted of a single chair for singer-songwriters. Organized crime was rampant in Lanzhou at the time, and after almost getting shot on one outing to Double Hundred, Yan and his friends never returned. Later, some of Yan’s friends opened a club called Rolling Stone, with the idea to create a venue for their own bands. It wasn’t without its shootings — “the number one saxophone player in Lanzhou was also a mafia; he sent some people to this bar,” Yan recalls — but it did function as both a breeding ground for new ideas and a destination for touring bands. Yan had an eye-opening experience when the Czech-via-San Francisco duo Sabot performed at Rolling Stone. “At that time, I didn’t know post-rock. ‘What’s this… It’s jazz? No. It’s rock? No. It’s… Okay, something strange… That was like a festival. Everybody from every corner of Lanzhou showed up.’”

Yan Jun introducing Sabot at Rolling Stone, Lanzhou, 1998

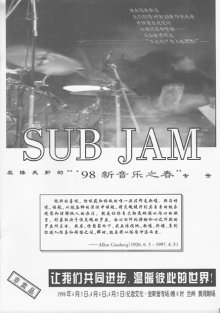

Hungry for more shows of this magnitude, Yan took a more active role as a promoter and organizer in Lanzhou. He found a bar large enough to host a festival, a 1,000-capacity venue dubbed Urban Express. He linked up with a local promoter, who was in the process of booking a Lanzhou show for Cui Jian — at this point, a major star — and they agreed to work together on a festival celebrating Anti-Beijing Rock in rejection of the first generations of Chinese rockers who had progressed to major label deals and stadium tours. The Cui Jian show lost money, so Yan’s “non-Beijing underground rock festival” was cancelled. Not satisfied with throwing away months of work, Yan featured all the bands he’d invited — including No, Tongue, PK14, and a dozen others — in a fanzine with the tagline “Spring of New Music ‘98,” forwarding their demo tapes to Guangzhou-based rocker Wang Lei.

Yan’s advice and Wang’s execution culminated in the Guangzhou Independent Rock Music Festival of April 1998. As the older generation of Black Panther and Tang Dynasty had ossified and become too commercial for Yan and his cohort, the Guangzhou fest was the first clear articulation of a rising movement. Bands like No and Tongue represented a shift from privileged native Beijingers dominating the Chinese rock scene to immigrants from other provinces creating tight-knit communities in migrant villages circling the city, challenging the rock scene’s status quo from the periphery. No’s front man Zuoxiao Zuzhou moved to Beijing from Nanjing in 1993 and quickly became involved in the Beijing East Village avant-garde art collective. Tongue relocated from the far-northwest city of Ürümqi (closer to Kabul than Beijing) in 1997 and took up residency in a squalid one-room apartment in a remote musicians’ commune called Tree Village. Sensing a new energy, a new movement, a new sound — not to mention following a new love interest — Yan moved to Beijing soon after.

Paradise Found, Paradise Lost: Beijing Rock in the Early 00s

Yan titled his 1998 fanzine Sub Jam: “Sub is related to sub-culture and something just emerging; Jam, of course, is about [making] some noise together.” This name and its embedded meanings would define his creative output for the next 15 years. When Yan first visited the capital in 1997 to write his book Beijing New Sound, he was already well-enough known to be sought out by key members of the underground rock scene, including Modern Sky label founder Shen Lihui, No’s Zuoxiao Zuzhou, and veteran rock critic Hao Fang. Yan moved permanently in 1999, immediately establishing a role as the scene’s resident philosopher. He wrote prolifically, romanticizing the solidarity and spartan living conditions in Tree Village and raising its protagonists — bands like No, Tongue, and The Fly — to the quasi-mythic status of Buddhist demon gods who alternately challenged and ignored the world above: “Devil Kings took their courage to resist the gods and assembled in the underground, but it was not as simple as a struggle for their lost paradise – clearly the main reason was that they were all very fierce, had a staunch attitude, dangerous thoughts and fresh music.”

The Beijing underground rockers at this time rejected the mainstream labels their predecessors had embraced, but there wasn’t a strong framework for DIY self-releases as an alternative. Modern Sky and the metal-focused Scream Records were formed in the late 1990s by musicians-turned-businessmen, insider members of the scene, but still operated according to old industry standards. Modern Sky in particular gained a reputation for focusing on quantity over quality, funding only the mixing and mastering part of the recording process and reneging on word-of-mouth deals if album sales didn’t meet expectations. Yan was in the middle of the struggle to maintain independence and underground feeling while facing the practical problem of how to record and distribute music from the scene: “Nobody knew how to bring this underground rock to the public. And these bands, they also didn’t know; they were just waiting… waiting for Scream Records, waiting for Shen Lihui, waiting for some unknown money, some unknown company.”

Yan entered this void in 2000, publishing a book of his collected writings and a compilation featuring Zuoxiao Zuzhou, Tongue, his hometown friend Wang Fan, and others under the name Noises Inside (内心的噪音). This was Subjam 001. Yan recycled his 1998 zine’s title, giving his new label the Chinese name Tie Tuo (铁托): “iron supporter,” diehard, a name that the members of the Tree Village community used to identify fellow insiders.

Over the next few years, Yan Jun grew to become the biggest DIY promoter of underground music in Beijing. He put out Subjam releases for Wang Fan, Tongue, early Beijing punks Brain Failure, and Nanjing post-punk transplants PK14, who by then had moved into Tree Village. He organized Chinese tours for kindred spirits within the Japanese avant-garde like Ōtomo Yoshihide and Sachiko M, and curated shows at various dive bars across the city like Happiness Palace (开心乐园) in Beijing’s university district and River Bar in the embassy district of Sanlitun. The scene around River Bar was the last bastion of the unified underground scene that had brought Yan to Beijing and inspired him to start Subjam in the first place. “[River Bar] was a family, the last illusion of our life. We called that utopia… Family every day, birthday party every day, everybody loving each other every day. It’s too heavy. It’s not possible to [maintain] this as real life… it had to break.”

In April 2003, the SARS epidemic that had spread across eastern China was finally acknowledged in the Beijing media, effectively freezing domestic travel and nightlife activity. One month before, President Jiang Zemin — a man who rose to power in the aftermath of the Tiananmen protests and pushed Deng’s plan of economic reform into the red — retired, handing the Presidency to Hu Jintao and the Premiership to Wen Jiabao, known for his suspiciously ostentatious public displays of emotion: “It was a different time. No more Jiang Zemin, no more big, bad guy, but a nice guy [Wen Jiabao], who knows how to cry. So this crying leader changed the simple mind of rockers… Everybody thought, ‘There’s nothing to fight with.’ This was a big problem.”

Mainstream media had started to pick up on the new sound from Beijing. Tongue and prog-metal group Yaksa were featured on the cover of prominent magazine Popular Music (通俗歌曲), leading to in-fights within the Tree Village tie tuo contingent. Bands started asking for large guarantees, half of their members desperate to become financially successful stars and the other half maintaining a ‘Fuck you, we’re rockers’ attitude. “For me, this was the year of the death of underground rock, and the end of my post-teenage [years],” Yan laments. At the 2003 MIDI Music Festival in Beijing, after a gross display in which visiting Japanese band Brahman was pelted with garbage by young Chinese nationalists, Yan Jun realized his dream was over. “The dream was that rock ‘n’ roll is a line [we draw], a weapon. We [draw] this line to escape from that society, escape from all the ugly things, but one day, we realize there’s nothing pure.”

Moving Inward: Kwanyin, Olympics, The Tourist Culture

As the halcyon days of Beijing underground rock came to an end, Yan moved inward. “There will be more small concerts, more experimental activities, more strange musicians,” he wrote at the time. He developed a solo music career, producing no-input mixer and feedback noise alongside his evolving poetry and performance art practice. In the wake of the SARS scare, Yan hung out and frequently collaborated with hometown friend Wang Fan, Beijing-born video artist Wu Quan and Zhang Jian and Christiaan Virant of the ambient electronic duo FM3, who would gain international fame after inventing the Buddha Machine years later. This crew played around with event formats, seeking more intimate, casual, and non-rock contexts for their performances, such as a “10 Night Talk” series of discussions convened at each other’s apartments and a 24-hour show in Beijing’s 798 contemporary art district. In 2004, they launched Kwanyin Records, an imprint of Subjam focused exclusively on avant-garde, electronic, noise, and free-improv music.

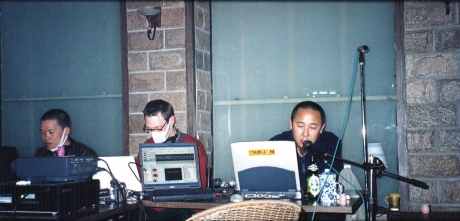

Zhang Jian (left), Christiaan Virant (middle), Yan Jun (right), and Wu Quan (not pictured) perform at Wansheng Bookstore, Beijing, April 8, 2003, days after the Beijing government officially acknowledges the SARS epidemic

In 2004, the Kwanyin scene went international. FM3 began playing isolated gigs in Europe in 2002 and returned in June 2004 for a three-date gig at the Louvre that financed a six-month European tour. Yan and Wu Quan took the opportunity to meet them in Belgium that October, their trip coinciding with a European tour for southern Chinese sound artists Li Jianhong and Wang Changcun. This semi-random overseas meeting of China’s leading avant-garde musicians was fruitful: Wang Changcun landed a contract with Brussels label Sub Rosa, and Yan Jun went home with renewed inspiration to build a culture around the Kwanyin concept.

In May 2005, Yan’s old River Bar associate Gao Feng opened 2Kolegas, a live-music dive bar located on a grassy field next to a massive drive-in movie theater in Beijing’s central business district. Within a month, Yan Jun launched Waterland Kwanyin, a showcase for the city’s weirdest and most extreme musicians — plus plenty of likeminded vagabonds just passing through — that would take place almost every Tuesday night for the next four-and-a-half years. Although 2Kolegas had more of a ‘noisy rock bar’ vibe than the austere, art-oriented venues he had experienced in Europe, Yan immediately seized on the feelings of warm camaraderie these weekly meetings fostered, a throwback to his beloved rock scene of the early 2000s: “When I went to 2Kolegas for the first time, I thought, ‘Wow, it’s another River! I love it!’ I forgot I wanted to find a quiet place.”

early Waterland Kwanyin. left to right: Wang Fan, Zhang Jian, Christiaan Virant, Wu Quan, Yan Jun perform as Spicy Boys

In the early days of Waterland Kwanyin, the core group remained Yan, Wang Fan, Wu Quan, and FM3. FM3’s Zhang Jian had come up playing with some of the earliest Beijing rockers, and his influence brought former Black Panther lead singer Dou Wei, Xie Tian Xiao of the early grunge band Cold Blooded Animal, and even Chinese rock godfather Cui Jian into the mix for improvised, one-off performances. Over the next few years, WK cycled through various trends and influences: Yan recalls that 2006 was dominated by laptop musicians, while 2007 and 2008 saw more activity from the harsh noise collective/label NOJIJI, no wave- and minimalist-influenced guitar music from a group of university bands calling themselves No Beijing, and more traditional-instrument-based improvisation from free-jazz saxophonist Li Tieqiao, zither master Wu Na, multi-instrumentalist Li Daiguo, and inveterate Chinese freak-folk provocateur Xiao He.

Waterland Kwanyin, 2005-2010. top left: Wang Fan; top right: FM3; middle left: Xiao He; middle right: Zhang Jian; bottom left: White (No Beijing); bottom right: H1N1 (Nojiji)

Yan considers early Waterland Kwanyin his “last utopia.” In mid-2007, he began to feel the center shifting once again, the centrifugal force of Beijing spinning out the WK scene as China prepared on a massive scale for the 2008 Summer Olympics. FM3 left for extensive tours of Europe and the US, and Wu Quan limited his involvement in the Kwanyin enterprise. As what Yan now calls “the spirit of pre-Olympic” faded, the audience changed: “Some moved away, changed jobs, moved on. Some just disappeared.” Suddenly, amid a smattering of the few remaining diehards, the audience was rounded out by two sure harbingers of decline: tourists and mainstream media. Although Waterland Kwanyin persisted through January 2010, Yan Jun spent the Olympic lead-up and fallout focusing on his music. “This is the end,” he thought at the time. “Too big, too warm, too open. [I realized] I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life as a party organizer.”

Nevertheless, Yan took the opportunity to organize on a much larger platform, striking a deal with UCCA, China’s foremost contemporary art center, to curate a monthly event series in 2010. This experience crystallized every dissatisfaction Yan had been feeling toward the post-Olympic Beijing cultural milieu in general and the evolution of the city’s underground music scene in particular. “They’re trying to do something very Western, professional, mechanical,” Yan told me in December 2010, days before the final Subjam UCCA gig. “Like I call, we talk, and we decide to do something. But no more support… I like to make something, not just organize something. I want to talk, to think with the organizer, with the venue people. [I like to] spend some time to eat something, drink something, to talk not about the concert, but about everything. You have to waste some time to create.”

posters from Yan Jun’s 2010 Subjam UCCA event series, designed by Ruan Qianrui

At UCCA, Yan Jun continually brushed up against the hyper-capitalist tendencies of Beijing’s contemporary art world. The trend he noticed toward the end of Waterland Kwanyin was much more pronounced at UCCA: “We did have some audience, but 99% were just tourists. This is a time of tourism… You get thousands of pieces of information, invitations, and suggestions, and you pick up everything as ‘I’m interested in this event, I’m interested in this guy,’ but you don’t have time to go to the concert, you don’t have time to listen to this guy. You don’t have any patience to focus on anything. Compared to several years ago, the underground time, it’s like everything you want 10 years ago, now you have it. This is your dream… And now… We’re just tourists from one new phenomenon to another new phenomenon, from one kind of music to another kind of music, from music to exhibition, from exhibition to party, to, you know… We just move, and make a mark on the map, and take a picture, ‘I’m here, bye bye.’ ”

Yan remains one of China’s best-known experimental musicians and organizers, and still hosts international artists attracted by Beijing’s reputation as an emerging frontier for new music. But he has willfully tightened his focus, his network, and his circle. He is currently conducting a “living room tour” of Shanghai, following a similar spate of un-commodifiable private concerts he gave to friends in Beijing last summer. In putting all of his energy into his own art practice — which may be most simply described as a deep meditation on the experience of embodied listening — he is trying to build “something more concrete than a party, something more sustainable.”

“Subjam is a medium,” Yan told me last month, as we shared a cab to meet UK vocal improv master Phil Minton, for whom he had organized a tour of China. Over the course of his long involvement with Chinese underground music — kickstarted by paroxysms of discovery and inspiration, tempered in loud, sweaty bars in the company of his self-selected and self-created communities, and, ultimately, repeatedly impeded by gentrification, globalization, and natural entropic decline — Yan Jun has kept a fire burning in his core. He uses Subjam to share this inner life: “I want to trigger people to a state where they can feel themselves.” In the process of continually re-inventing himself, he has transmuted the Chinese avant-garde from something new to something unique: “Ten years ago, I [thought] new is good, different is good; it is what we are trying to find and trying to create. Now I know ‘new’ is just an illusion. ‘New’ is not my logic, it’s capitalism’s logic. ‘New’ is a lie, actually. It’s not about possibility; it’s just killing the possibility… Real possibility means you have to keep something in the unknown, in the mystery, in the chaos. So now I rethink everything in my mind [from] 15 years ago, 10 years ago, and now I feel very happy… the next step will be more clean.”

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, next Sunday we have a concert, please come with your instrument.’ No. No more. I want to talk with people. ‘Why do we do this?’”