The 1970s are often referred to as the heyday of avant-garde jazz and improvised music in Europe, especially in England. Festival and concert performances were frequent and, in the early years, even major labels got in on the action. Part of that had to do with the potential appeal of this music to audiences seeking psychedelic and progressive sounds. For example, there was no obvious indication that the People Band LP on Transatlantic (1968) was a balls-to-the-wall free jazz album, produced as it was by none other than Charlie Watts. Cross-pollination between the worlds of art rock and improvised music wasn’t that uncommon, either – saxophonist and composer Elton Dean (1945-2006) worked with the Soft Machine from late 1969 into 1972, appearing on their albums Third, Fourth, and Five (all released on CBS) as well as countless live recordings that have surfaced over the years. He lent an acrid tone and loquacious approach to a band that, as they evolved, narrowly walked the line between clinical reserve and rugged expressiveness, and his presence certainly pushed the band to extraordinary heights. Dean was recruited, alongside trumpeter Marc Charig and saxophonist Lyn Dobson (who only lasted a short time), from the sextet of pianist-composer Keith Tippett (who would briefly join King Crimson). A look at Tippett’s first LP You are Here, I am There (Polydor, 1970) shows the ensemble as young, hip and Beatle-coiffed – an image concomitant with Modish UK counterculture.

By the early-to-mid 70s, creative music was once again an underground phenomenon in Europe, with most major labels pulling out and musicians self-financing their work (though festivals and the media were still quite forward-leaning). Much as in the US, artist-run labels sprouted up to offer musicians a chance to document their processes on wax. Expatriate South African bassist Harry Miller (1941-1983) and his wife Hazel started Ogun Records to document the British modern jazz scene during the decade, drawing significantly from the exiled South African community surrounding pianist Chris McGregor. Recalling the lush landscapes of Tippett’s work as well as the exuberant and freewheeling suites of McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath (two of the saxophonist’s employers), Dean formed Ninesense in 1975. The personnel included Miller, Tippett, Charig, drummer Louis Moholo, trombonists Nick Evans and Radu Malfatti (Switzerland), tenor saxophonist Alan Skidmore, and flugelhornist Harry Beckett. Ninesense released two LPs on Ogun, Oh! For the Edge and Happy Daze, and toured extensively through the latter half of the 70s. This fertile period has given us the recently unearthed The 100 Club Concert 1979 (Reel Recordings).

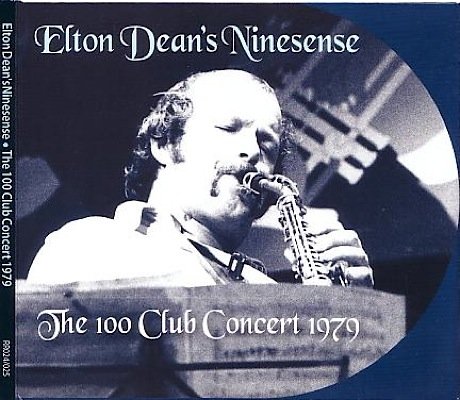

Unlike the many bootleg labels that present this music in less-than-quality format, Reel Recordings has sought to bring rare performances to light both legally and in good to excellent sound. This particular Ninesense set (two discs worth) is culled from two cassettes made by Italian superfan Riccardo Bergerone with the musicians’ approval. And while the sound is a bit raw (the piano is a bit distant), the vast emotional and conceptual canvas of Dean and Ninesense are clearly on display. Miller and Moholo are an incredibly well-synced team, swirling and ebbing in a rhythmic flow that, while forceful, carries this challenging music with the majesty it needs. Indeed, there’s something quite stately about the arrangements, due in part to the instrumental breadth and how Dean has paced the voicing (wide intervals and overlapping sections). With a combination of nine very individual personalities (or ten if you count the appearance of trumpeter Jim Dvorak on disc two), it would be easy to imagine Ninesense being blowout-prone. However, contra the Brotherhood’s music (which was often quite ragtag in its sonic appearance), Ninesense isn’t so rough around the edges. The palette and approach, as open as it might seem, are realized with captivating deliberateness – one can imagine a subtle and linear herding of Evans and Malfatti’s garrulous trombones as they duet in “Nicrotto,” joined by swooping brass, arco bass, and reeds. This music revels in elegantly threading an area between control and freedom, and it’s a really fascinating listen.

Following the dissolution of Ninesense later that year, Dean continued to work in small groups, including with fellow ex-Softs bassist Hugh Hopper and in Canterbrury offshoot bands like drummer Pip Pyle’s (Gong, Soft Heap, National Health) l’Equipe Out and guitarist Phil Miller’s (Caravan, Hatfield and the North, National Health) In Cahoots. However, much of Dean’s subsequent work hewed closer to free improvisation, such as recordings with American trombonist Roswell Rudd, pianist Howard Riley, saxophonist Paul Dunmall, and others. The 100 Club Concert 1979 is a fitting and intense tribute to his admittedly somewhat underground legacy.