I first saw Girl Talk in 2007, shortly after the release of Night Ripper. Drunken college kids filled the floor and stage of the tiny venue. Hopped up on a continuous stream of Top 40 hooks, they surrounded Greg Gillis, jostling his tiny table of laptops and electronics like rioters trying to tip a police car. Shirts were off. Gillis’s keyboard was covered with saran wrap to protect it from the rain of sweat made airborne from the frantic dancing.

I’m not going to say those those kids owed their good times and undoubtedly massive hangovers to John Oswald, though he certainly predicted them. In 1985, the Canadian composer presented a paper to the Wired Society Electro-Acoustic Conference in Toronto titled “Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative.” The paper is short, and sets about making a point that now seems so self-evident as to be unnecessary: he argues “a sampler, in essence a recording, transforming instrument, is simultaneously a documenting device and a creative device.”

To our 2012 ears, accustomed to hearing Kanye top the charts by rapping over King Crimson, this sounds plain as day. It’s like someone wrote a paper arguing that you can compose a great pop song on a six-stringed something called a “guitar.” Though, remember, this is 1985. Though artists have been repurposing bits of recordings since the early days of musique concrète, the practice hadn’t spread far beyond the world of hip-hop — even the very high-profile Queen/Vanilla Ice fiasco was still half a decade off.

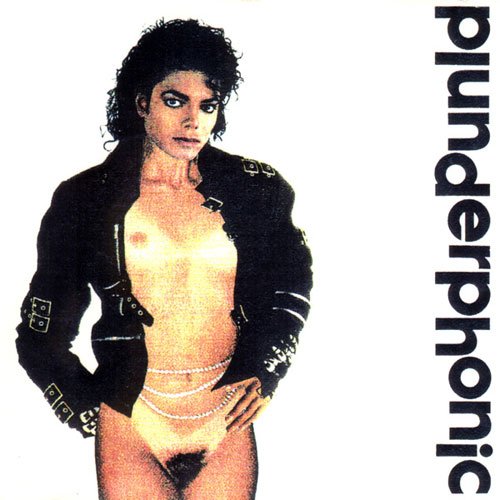

What makes this more interesting than your run-of-the-mill academic armchairing is the fact Oswald follows up his paper with Plunderphonics, a 24-track album that lays out a vision of the sampler as instrument. Unlike its contemporaries in the world of hip-hop, Plunderphonics doesn’t merely use prerecorded music to backbone a new creative work, something to buttress and build off of. Instead, the manipulation of samples is the focus — nothing new is added, and most tracks have only a single source material. The editing and handling of the samples is the point of creative action.

He doesn’t shy away from his target, either. Right from the start he goes after the King of Pop. Listen to “Dab,” Oswald’s take on Michael Jackson’s “Bad.” It’s mangled, concussive, and nearly twice as long as the original. At first, the song is recognizable, just jumbled as if being played off a severely scratched CD or on a bumpy bus ride. But just as the liner notes claim, “as it progresses the levels of complexity and abstraction increase.” The song essentially shows the various degrees to which a song can be mutated. It leaves you with the question: at what point does deserve the distinction of being a work in its own right.

Elsewhere, Oswald shows the versatility of this type of composition. On “Dont,” Elvis is slowed and stretched until his ghostly croon sounds as if it’s coming from the back of a cave filled with malfunctioning clocks. On “Pretender,” Dolly Parton goes through puberty right on tape, her voice dropping until it would fit into any Lynchian hallucination. The final track, “Rainbow,” works over the Wizard of Oz’s most famous performance into an eerie drone piece that would be right at home on a Caretaker album. Really, the technique and result are unbelievably similar.

Back in 1985, Oswald asked the audiophiles, futurists, and academics in Toronto to “imagine how invigorating a few retrograde Pygmy … chants would sound in the quasi-funk section of your emulator concerto. Or perhaps you would simply like to transfer an octave of hiccups from the stock sound library disk of a Mirage to the spring-loaded tape catapults of your Melotron.” Scrolling through my records now (side note: when will “scrolling” completely overtake “flipping” as the go-to verb in that sentence) it’s like he’s describing half the artists getting coverage here at TMT. He’s describing Co La; he’s describing Eric Copeland; he’s describing Heat Wave and Macintosh Plus. I wonder if he’s ever met James Ferraro? I’m sure they’d find much to talk about.