Leonardo da Vinci once said, “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” But if an artist’s work has traditionally been like a newborn foundling left in a bundle on the church steps, some present-day creators seem to approach the act of publishing as more of an open adoption. Hither to now, the clingiest parents have been filmmakers. George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Ridley Scott have all come under fire in the past decade-and-a-half for tinkering with their masterpieces. Who knew that, all this time, Richard Hell was just waiting to get a piece of the action?

When Destiny Street was first released in 1982, Hell’s interest in music had taken a back seat to his interest in being high, and the resulting album never lived up to its full potential in its creator’s eyes. That’s why when Hell acquired the rights to the record five years ago, he sat on it until it went out of print and then set out on a quest to remake it. The result, Destiny Street Repaired, was a peculiar beast: not exactly a reissue, since the vocal and lead guitar tracks were laid down specially for this edition, but hardly a new album either, since Hell’s stated intention was to hew as closely to the source material as humanly possible. Destiny Street Repaired is sure to be a divisive record, but ultimately its value comes down to two critical issues: (1) Is the album any good? and (2) How does it measure up to the original recording?

Happily, the answer to my first question is a resounding “yes.” Destiny Street is a fine album, arguably better written than Hell’s exponentially more talked-about solo debut. While Blank Generation rotated mainly around stuttering, angular guitar constructions that embodied the bitterness and anxiety of Hell’s lyrics, the songs on Destiny Street show a more refined pop sensibility. High-energy tracks like “The Kid with the Replaceable Head” and “Lowest Common Dominator” are more direct than even the most accessible cuts off Blank Generation, but thanks to the deceptively convoluted guitar contortions of Robert Quine (enhanced in this edition by Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell, and Ivan Julian on the solos), they remain fully engaging. And while it would be a gross oversimplification to say that Hell’s prior work lacked tenderness, Destiny Street finds him bringing his sneer to heel, particularly on the country-tinged paean to maturity, “Time.” The set is rounded out by a bevy of covers that contribute to the general sense of optimism, including The Kinks’ “I Gotta Move” and Them’s “I Can Only Give You Everything.” The best of them, however, is a melancholy rendition of Bob Dylan’s “Going Going Gone” that sounds like it was written with Richard Hell in mind.

So that’s good news. Destiny Street is a great album, a criminally overlooked work by a brilliant songwriter at the peak of his craft. That still leaves the question of whether such dramatic reconstructive surgery was necessary to resuscitate this buried gem. On this score, regrettably, my assessment is a little more ambivalent. Though the original CD pressing is unavailable, I was able to download a couple album cuts off one of the many, many Richard Hell anthologies available on Amazon (and might I say that Mr P has been very dodgy about telling me where I can file my expense reports). Destiny Street Repaired certainly boasts superior sound quality and some truly excellent guitar work by Ribot et al, but this in and of itself doesn’t seem like justification. After all, couldn’t The Sex Pistols, in theory, record a much more polished version of Never Mind the Bullocks if they were to remake the album today (with a competent bass player, no less)? Frankly, none of the original recordings that I sampled sounded so bad as to elicit such disappointment on their author’s part. Just as with the Blade Runner “Final Cut” and the 20th Anniversary edition of E.T., this appears to be a case of an artist trying to fix something that wasn’t broken in the first place.

Only the album’s title track emerges from this redacting as something new, and indeed integral to Hell’s catalogue. The re-record adds an additional three minutes to the original’s runtime, but even more importantly, Hell’s peculiar narrative about meeting a younger version of himself and trying to impart wisdom to the youth through play takes on a whole new significance in light of the Destiny Street Repaired project. It’s the kind of lighthearted twist that lends a new poetic resonance to the whole album. Nevertheless, to engage in revisionism on this level seems indulgent, and the fact that he’s effectively made this the only version available to fans (unless you want to freeload it or pay upwards of $40 for a used copy on Amazon) is obnoxious to the highest degree. Yet Destiny Street is too good of an album to write off, and if you have to choose between listening to the revised edition and not listening at all… well, then Destiny Street Repaired is the lesser of two evils by a longshot.

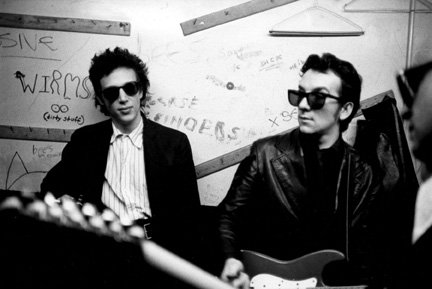

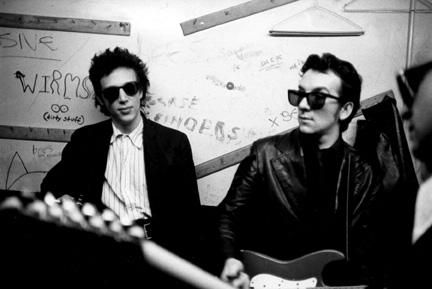

[Photo: R. Bayley]