“This album’s really a feeling. It’s like, ‘Welcome to yourself.’ You are now here. We are here. This country was born and raised on violence, and now we are adults — and we’re violent,” explains Schoolly D aka Jesse B. Weaver Jr. in a 1994 interview with Gabriel Alvarez. Schoolly makes it known where he stands in the age-old debate of art imitating life vs. life imitating art. However, one would be remiss to assume that Welcome to America is yet another “ghetto CNN” record. The tales contained on this album’s 13 tracks are not so much news reports as they are a series of psychological profiles, and the black bogeymen Schoolly bluntly portrays represent the realization of conservative white America’s deepest fear: drug-crazed, gun-toting black gangsters run amok, raping and murdering at will, without consequence or remorse. Hide your daughters! Arm your sons!

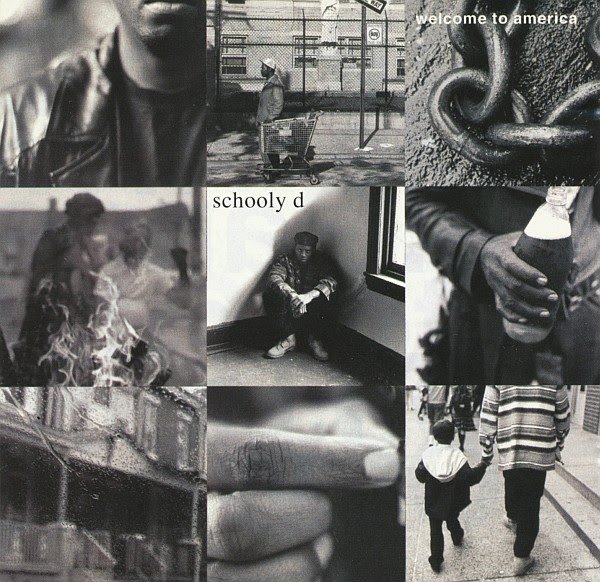

Of course, Schoolly’d been purposely pissing off pastoids for his entire career, which by this point was already ten years deep. The difference this time around is that much of the cartoonish humor and Black Nationalist imagery of his prior efforts have been stripped away, while the sex, drugs and violence are all taken to post-parody extremes. For example, in place of crudely drawn asses or a red, black, and green banner, the cover art now features black and white photographs of urban decay; similarly, “Peace to the Nation” (a song off 1991’s How A Black Man Feels) is replaced with “Peace Of What,” a cynical diatribe in the tradition of Main Source’s “Peace is Not the Word to Play;” and where once Schoolly rapped about his mom waving a gun at the girl he snuck into his room after hours (on “Saturday Night”), he now gets a woman high, takes her out to dinner, brings her home, kicks her ass, fucks her, then shoots her in the head (on “I Wanna Get Dusted”). The carnage escalates on “N****s Like Me,” in which Schoolly raps:

“All I wanna do is get you in my caddy/ I don’t give a fuck about your mommy or your daddy/ ‘Cause n****s like me, don’t you bother/ We don’t give a fuck about a bitch-ass father/ At the table I eat up all the dinner/ I pinch your granny on the ass like a winner/ I fuck your little sister/ I got the ho calling me Mister/ Big Dick, real slick, real sick/ I fucked the ho then I dropped her real quick/ I put your little brother in a gang/ I sit back and watch the n***a bang.”

In a sense, this album is like a gangsta rap version of The Last House on the Left, except instead of, “To avoid fainting, keep repeating ‘it’s only music,’” the Intro tells us most invitingly and accommodatingly, “All the motherfuckers is welcome: hardcore n***s, gangsta bitches, ho’s, motherfucking bitches…” Stephen Thomas Erlewine’s Allmusic review states, “It helps that the record contains the best music he has ever recorded, although the best moments can’t hide the fact that Schoolly D doesn’t have the lyrical grace of the rappers that followed in his footsteps.” While I partially agree, in that I think the beats on here are some of the best Schoolly has ever produced (more on that later), I have to add that if you’re looking for “lyrical grace” in a Schoolly D album, then you’re totally missing the point. First of all, the man improvised the majority of his vocals, so there’s that. Second, and more importantly, it was never Schoolly’s intent to woo his audience with beautiful turns of phrase, so for him to dress up his rhymes simply because the game had changed would be to cater to expectations of how he should sound, an act antithetical to everything he ever represented. Grace and subtlety are absent from his words, but so too are they absent from the world he describes. After all, this is not Philadelphia, The City of Brotherly Love; this is Philadelphia, The City That Bombed Itself. Hence, the language, like the artwork, is all black and white.

As entertaining and provocative as the lyrical polemics are, it’s the beats on Welcome to America that are perhaps most appealing and illustrative of Schoolly’s artistic growth. I use the word “beats” as a standard term for hip-hop production, but it is traditional instrumentation that serves as the backbone of this album’s production side. While all of his prior releases relied primarily on drum machines, samples and turntables, here, a full band — including Schoolly himself as well as a young Scott Storch (pre-superproducer trappings) on keys — is added to the mix. Uninformed listeners who equate ‘hip-hop bands’ with the abysmal rap rock fad of the late ’90s rather than the old studio musicians employed by labels like Sugar Hill Records can just check that pretension at the door.

Remember, Schoolly is the rapper responsible for such classic numbers as “I Don’t Like Rock N’ Roll” and “No More Rock N’ Roll,” so it’s safe to assume that even quality hard rock-inspired production ala the Beastie Boys or Run DMC was the furthest thing from his mind when he entered the studio. “I grew up on Funkadelic, Parliament, Buddy Miles, Average White Band, Tower of Power, Earth Wind & Fire,” says Weaver, and the MC’s musical tastes likely shed some light on the direction the musicians received from himself and executive producers Chris Schwartz and Joe “The Butcher” Nicolo, as the beats on here are best classified as heavy funk meets Philadelphia soul. And though one might look to connect this sound with that of The Roots, who also employed Scott Storch and released their debut, Organix, just a year prior, it’s the criminally slept-on illadelphia hip-hop trio The Goats who provide a better basis for comparison, as their two albums — 1992’s Tricks of the Shade and 1994’s No Goats No Glory — were both produced by The Butcher as well.

Another plausible inspiration was the affiliation of Schoolly D with film director Abel Farrara, who’d pestered Schoolly into allowing him to use his music as the soundtrack for the 1990 classic King of New York starring Christopher Walken. Though Schoolly wouldn’t physically sit down to score an entire film on his own until 1996’s Lowball, it strikes me as far from inconceivable that Schoolly was by 1994 already looking toward a second career as a film composer. Furthermore, witnessing firsthand how well his music complemented the on-screen action of King of New York (and vice versa) definitely could’ve encouraged him to further explore the already-cinematic elements of his sound. Note the gunshots and siren-like horns on “I Know You Want To Kill Me” and the resonant buildup giving way to a basic pimp-strut bass line on “I Shot Da Bitch.” Devices such as these and others are used throughout the record to build and release dramatic tension, crafting a series of audible story arcs, the last of which culminates with “Stop Frontin,” which uses a sequence of cinematic skits in place of a hook.

While Welcome to America’s finale, “Another Sign,” doesn’t so much resolve the album’s conflicts as it reiterates or summarizes them, it does offer up a poignantly sobering narrative: “Sitting at the breakfast table smoking me a spliff/ Say what’s up to my little sis/ Thirteen and already knocked up/ But the little black daddy don’t give a fuck/ Our momma mad ‘cause she gave up/ Took her to church every week but couldn’t save her/ I got a daughter and a son/ Before he say “daddy” little n***a might say “gun”…” The bleakness is exacerbated by a beautiful, if hopeless, gospel chorus of male and female crooners harmonizing along with the song’s main blues riff. Meanwhile, the rhythm section’s intoxicating effect strikes an ingenious counterbalance. Family dysfunction never sounded so goddamn smooth.

For further discussion of Schoolly D’s production prowess, check out this post I contributed to the t.r.o.y. blog.