European free music, experimental, and lowercase improvisation would look and sound quite a bit different without the presence of England’s Spontaneous Music Ensemble, active from 1966 until the death of constant fulcrum and percussionist John Stevens in 1994 at age 54. Stevens was a fixture in West London and studied music while in the Royal Air Force where he formed relationships with other notable UK modernists, alto saxophonist Trevor Watts and trombonist Paul Rutherford (1940-2007). Influenced by British bop tour-de-force Phil Seamen, Stevens was something of a regular at the storied Ronnie Scott’s club, but searching for something beyond bebop led him, Rutherford and Watts to form a group that quickly developed into the Spontaneous Music Ensemble.

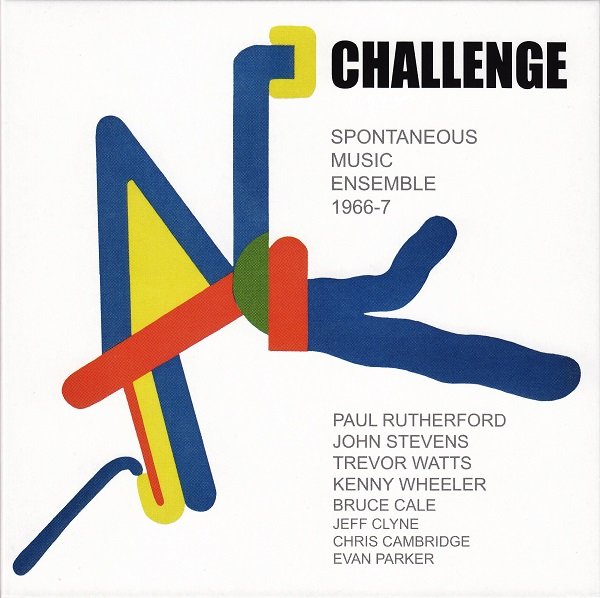

While a name like “Spontaneous Music Ensemble” might imply a sense of complete openness and absence of predetermined form, the SME at its outset was decidedly more reined in. Taking cues from American forebears like reedman Eric Dolphy (whose untimely death was still fresh on musicians’ minds) and saxophonist Ornette Coleman, the SME played compositions from the books of its three principals. Curiously, it didn’t take long for the group to record, and with Canadian expatriate trumpeter Kenny Wheeler and Australian troubadour bassist Bruce Cale in tow (replaced on two tracks by premier London bop bassist Jeff Clyne), the SME cut eight pieces for issue on the tiny Eyemark label as Challenge in 1966. Long out of print and in heavy demand, the Emanem label reissued it with two extra tracks in 2001, and now that CD has once again become available.

“E.D.’s Message” starts the proceedings and is certainly Dolphy-esque in its sprightly charge, though the ensuing improvisation from the horns is a tumbling swath of variegated colors, bright but with a density more akin to the music Albert Ayler and the New York Art Quartet were creating in East Village lofts. Watts’ acerbic wail is thoughtfully behind the beat and takes center stage with the burbled goads of his fellow hornmen, while Stevens takes a mostly unaccompanied solo suspended between Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, and Sunny Murray before the ensemble makes a pensive reentry. “Club 66” has a curiously isolationist thread to its improvisations, with trombone, flugelhorn, alto, and bass each taking pensive, exploratory themes against Stevens’ impulsive shimmer, bookended by a clarion near-waltz theme that recalls the writing of trumpeter Booker Little. “Day of Reckoning” is tough and declamatory at its anthemic outset, but the interactions between brass/reeds, bass, and percussion display a delicately taut interdependence. It is clear that even when the SME engages the structural trappings of jazz in a “free-bop” setting, the nuanced improvisations between those lines are a greater focal point and may actually have little to do with thematic material. That dichotomy is in itself quite interesting and, while it eventually required abandoning tunes altogether, the isolated movements that lie between the frames create a uniquely tense environment.

The CD reissue of Challenge also includes a lengthy open improvisation, “Distant Little Soul,” from early 1967 with Stevens, Watts, saxophonist Evan Parker and the obscure bassist Chris Cambridge (who wrote the liner notes to the original LP); Watts doubles on piccolo here and his flights mesh beautifully with Parker’s slick soprano inroads. While not particularly sought out by record companies, the SME did wax a number of LPs after Challenge, and a track like “Distant Little Soul” is indicative of the group’s exploratory dedication whether or not a formal recording session was possible. By 1968’s Karyobin (Island), tunes had been dropped in favor of incisive free conversations with defined lengths, and while open improvisation was the group’s focus, it was with a shared, evolving language that emerged through constant playing and workshopping. Even as strict “heads” were jettisoned, Stevens did workshop motives for improvisation such as the “Click Piece” and the “Sustain Piece,” utilizing short, sharp sounds or long tones as a basis for group playing with the idea that people of varying skill levels may have much to contribute.

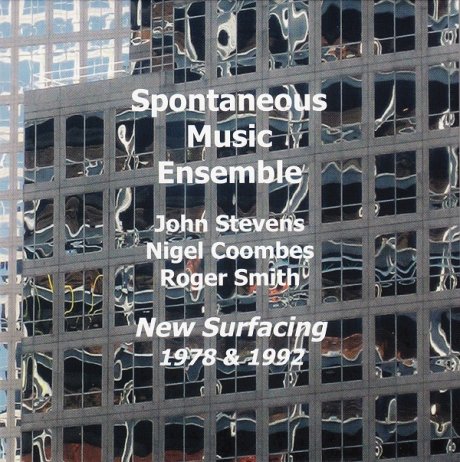

By the early 1970s the SME had pared itself down to consist only of Watts and Stevens, with the latter employing an extremely small kit; he also began playing cornet as well as using his voice. As the music evolved, the SME’s improvisations demanded as much attention to silence and detail as they did a thick sonic palette. Adding onto the small frame of a dryly tuned, minimal drum set and breath/voice was an occasional but significant necessity, fleshed out in such combinations as the Spontaneous Music Orchestra and a variety of mid-size groups. Though Watts left the SME by the late 1970s to concentrate on his own groups Amalgam and Moiré Music, Stevens continued the ensemble with younger second- and third-wave British improvisers including guitarist Roger Smith, violinist Nigel Coombes, cellist Colin Wood, and (later) saxophonist John Butcher. Smith, Coombes, Wood, and Stevens comprised the SME of Biosystem (1977), which was released on the Incus label (and reissued on Evan Parker’s psi label), and saw the SME texturally reshaped into a sparse and darting strings-and-percussion unit.

New Surfacing consists of two live recordings from 1978 and 1992 with Stevens, Coombes and Smith, and presents what were previously cassette-copy fragments (originally issued on separate Emanem and Konnex CDs) in a definitive, straight-from-the-masters edition. The 1978 pieces were recorded in Newcastle as part of a set opposite multi-instrumentalist Steve Beresford’s duo with cellist Tristan Honsinger; while decidedly low-fidelity, the material represents excellently a quality that emerged in later SME music — that of roomy drift and frustrating “doldrums” against fidgety group impulsions. In fact, while it is fair to say that deep listening is a major part of the SME aesthetic, to the point that Stevens and company developed an intuitive language of play that went beyond even the subtlest aspects of jazz communication, independence and non-listening were also an important hallmark.

It seems like this counteractive improvisational sense was clearer in the group’s later edition, as Stevens plays against (or flat out rejects) the soaring lines of Coombes’ violin and Smith’s detuned, seasick acoustics just as much as he interleaves his sounds with theirs. It’s reminiscent at times of Weasel Walter’s boisterous clatter and anti-motion, as Stevens hacks, patters, and obsesses in direct, absurd contrast to the string players’ complex and sometimes romantic phrasing. This is even more clearly evident on the 1992 London piece, “Complete Surfaces,” which is taken from a crisp DAT recording and albeit with less ghostly spatial reverb, offers a punchier view of the music’s latticework with Smith’s guitar alternating percussive asides to Stevens’ nattering paths. New Surfacing doesn’t present the last recordings in the SME discography — for that one would have to hear A New Distance, recorded in 1994 for John Butcher’s Acta label (reissued later on Emanem), with Butcher’s tenor in place of Coombes’ violin for a decidedly rugged take on the group’s speedily obstinate improvisations.

A quick word about the Emanem label, which has tirelessly documented the recorded activity of the SME for close to 40 years: while Stevens’ music (which also included such groups as Detail and Away, among others) was by no means unheard, the evolution of his instrumental approach and the SME’s palette often happened apart from any sort of commercial recording schedule. Luckily, Emanem founder Martin Davidson has been able to release a significant amount of that music, and it’s hard to imagine that Stevens’ stature (or that of some of his contemporaries) would be the same otherwise. Originally based in the UK, Emanem has shifted home base a few times over its existence, including stints in the US and Australia, and recently relocated to Spain. Their catalog of contemporary and historical improvisation is impressive and well worth investigating beyond the Spontaneous Music Ensemble axis.