To witness someone speak in tongues is a surreal experience. In a rapturous state, an individual will mumble, burble, or make some otherworldly sounds, seemingly divined from unknown forces. For the speaker, the vocal incarnations are an unconscious gift. Faith channels mystic forces and the believer becomes a holy mouthpiece. However, for the unenlightened, this phenomenon defies reason and credibility. Daily life conditions us to seek cause from effect, so when we are confronted with an unmoved mover, logic is thrown into disarray. Sound is incongruent with meaning.

For David Byrne, the act of speaking in tongues was an inspiration. The title of Talking Heads’ fifth studio album, according to Byrne, was an artifact of his fascination with preachers. “When people go into trances, they garble in a strange language… I’ve seen it in movies; I’ve seen it face to face as well. It was a woman in a church, and she was talking in a fairly excited tone of voice, and all of a sudden these phrases came out of her.”

“I think my words make about that much sense sometimes,” he joked during an appearance on Late Night with David Letterman. “Well, they make sense, but not if you try and figure them out.”

——

——

After Talking Heads’ sonically adventurous album Remain in Light, the group went on a two-year hiatus, pursuing separate projects. Byrne made The Catherine Wheel, a soundtrack for a ballet by his choreographer girlfriend Twyla Tharp, bassist Tina Weymouth and her husband/drummer Chris Frantz released their first album as Tom Tom Club, and guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison released his first solo album, The Red And The Black. Tensions were reportedly high during the band’s stint with producer Brian Eno on Remain in Light. The band produced the next Talking Heads album with all songs credited to David Byrne/Chris Frantz/Jerry Harrison/Tina Weymouth. In the book Talking Heads by David Gans, Frantz explains that, “[On Speaking in Tongues] we [didn’t] have the extra aggravation of Eno always trying to make something weird or saying, ‘That’s too ordinary. We have to do it this way to make it weirder.’”

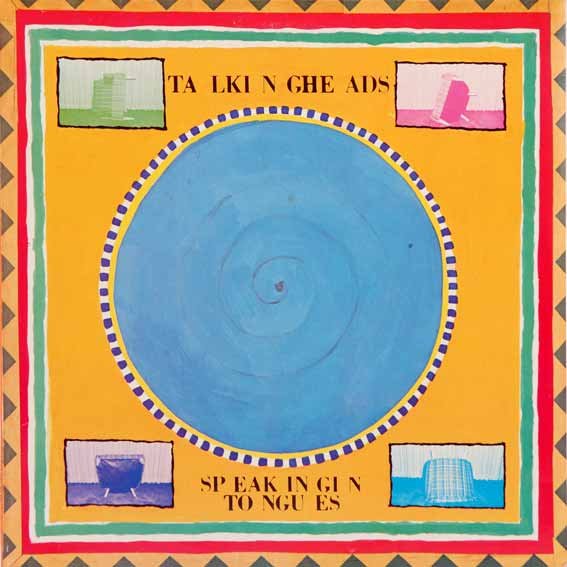

From its album cover to the music, Speaking in Tongues presents itself as a looser and more fun record than its predecessors. Limited-edition copies of the album featured plastic envelope packaging with clear discs designed by artist Robert Rauschenberg while the standard edition was painted by Byrne. Painted onto old white sleeves from test pressings, Byrne’s design is a whimsical swirl of pastels with four photographs of what he called a “drunk chair.”

Once the listener opens the packaging and plays the record, the true experience of Speaking in Tongues is revealed. The opening track, “Burning Down The House,” drifts in from silence and declares Talking Heads’ commanding presence. Seeing as the album was the band’s commercial breakthrough, it is fitting that it begins with their first and only American top 10 hit. The song inspires letting go, while a curious mix of synthesizers and guitars make it both strange and appealing. It is also the premier funk crossover song for suburbia. Byrne lifted the chant from Parliament Funkadelic and with it came the “Tear the Roof off the Mother Sucker” attitude.

The rest of Speaking in Tongue’s first side builds off of the energy of “Burning Down The House.” The preeminently silly “Making Flippy Floppy” and slippery “Girlfriend Is Better” infuse more distinct synthesizers and characteristically new wave solos. Byrne’s distinct vocals carry fractured melodies with style and swagger — it’s difficult to hear the lyrics “stop making sense” without envisioning Byrne’s slender frame enveloped in a giant white suite. However, on “Slippery People,” Byrne shares vocal duties with The Staple Singers, who play the roll of congregation for a gospel-style call and response. “What’s the matter with him?” Byrne demands over and over. If, at this point, it feels like madness is beginning to swallow the record, the choruses’ promise that “He’s all right” may offer comfort.

On Side Two, the songs are more varied and, ultimately, more comforting. The album closes with “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody),” a beautifully simple yet effective love song. The title’s origin refers to the fact that everyone apart from Frantz plays instruments on which they’re not proficient, repeating a “naïve” melody. Though it lacks a cohesive narrative, isolated lines are poignantly intimate and honest. It is touching to hear Byrne croon, “Home — is where I want to be/ but I guess I’m already there.”

Between fits of ecstasy and moments of reflection, Speaking in Tongues lives up to its name. One can ruminate on the album’s lyrics, but ultimately the group matches mode and function to make an impression. And as far as the music is concerned, Talking Heads’ expansion on new wave and funk is as inventive and catchy as anything in their catalogue. To dissect specific meaning from Speaking in Tongues is to separate the album from its inherent message: stop making sense and start listening.