2008 was a strange, frustrating year for movies. Just as major studios were shuttering their "indie" and art film subsidiaries, the simple storytelling and strong characters that animate low-budget cinema created the year's most memorable theater-going experiences. From the fucked up family in Arnaud Desplechin's A Christmas Tale to the desperate friends in 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days to the girl-and-dog bond that powers Wendy and Lucy, this year's strongest films were driven by people and relationships, not exploding cityscapes or CGI animation (Wall-E being the exception that proves the rule). In the past 12 months, Charlie Kaufman made his triumphant directorial debut, as two old greats -- Woody Allen and Jonathan Demme -- got their grooves back. Even the most effective documentaries of the year, like Man on Wire and Dear Zachary, focus on personalities rather than politics or intrigue.

Who knows what the future will hold for the film industry? It's a shame to watch independent film lose the patronage and visibility of the studios. But if our favorite movies of 2008 make anything clear, it's that the best aspects of cinema sell themselves without costing a thing. —Judy Berman

----

----

----

Synecdoche, New York (Dir. Charlie Kaufman)

Synecdoche, New York (Dir. Charlie Kaufman)

[Sony Pictures Classics]

by Stabish

How do you represent through a concrete, visual medium something so nebulous, unpredictable, dizzyingly profound, and maddeningly mundane as life itself? In Synecdoche, New York, a two-hour film that felt like a lifetime in the best possible way, Charlie Kaufman responded to this challenge by displaying with painstaking detail one man's spectacular failure to do so. Philip Seymour Hoffman's bewildered yet determined portrayal of theater director Caden Cotard pointed to the essential human truth that his character sought vainly to realize on stage: life is painful and confusing, dictated largely by forces outside of our control, and punctuated seemingly at random by fleeting moments of such transcendent joy that we continue living until we lose the ability to do so. Typical Kaufmanian inventions like the comically massive scope of Cotard's play and a house perpetually on fire aside, Cotard's life was quite ordinary. He loved, lost, desired, had children, got sick, went to work. Kaufman's directorial debut secured its place among the year's most worthy films by rendering this life into a statement both fantastically simple and truly astounding, showing us how the sheer amount of ordinariness packed into a single life is itself extraordinary beyond comprehension.

Synecdoche, New York - Sony Pictures Classics - Review

----

----

----

A Christmas Tale (Dir. Arnaud Desplechin)

A Christmas Tale (Dir. Arnaud Desplechin)

[IFC Films]

by Derek Smith

Arnaud Desplechin's formally audacious, hilariously vicious take on the annual home-for-the-holidays reunion film was a wolf in sheep's clothing, merely a guise for the director's pet themes of family, surrogacy, and the ways that the blood lines that tie us together can strangle us if we try too hard to tear free from them. As in his equally masterful Kings and Queen, Desplechin's deft handling of the widest range of emotions -- often within the same scene, occasionally even within the same moment -- and the variety of overt stylizations, from irises and chapter titles to direct addresses to the camera, imbued the proceedings with a buoyancy and boisterousness as the pure, unadulterated cinematic verve carried us magically, gleefully from one scene to the next. Desplechin's ability to mine the comical from the dramatic, and vice versa, so naturally and effortlessly makes other director's attempts to do the same come off as comparatively hackneyed and forced. That this profound sense of realism and truth in the character's relationships with one another worked so seamlessly within a stylistically elegant and smartly constructed film makes it equally effortless for me to claim A Christmas Tale as my favorite film of the year.

A Christmas Tale - IFC Films - Review

----

----

----

Sukiyaki Western Django (Dir. Takashi Miike)

Sukiyaki Western Django (Dir. Takashi Miike)

[First Look Studios]

by Dustin Luke Nelson

If the jury was still out on Takashi Miike in America, Sukiyaki Western Django ought to provide some clarity. Miike is undoubtedly a master of the genre film, and Sukiyaki may be something of a generic masterpiece. Shot as a western, with an all-Japanese cast, speaking awkward, phonetic English, in a small town in Nevada -- where all the signs are written in Japanese -- the film is hysterical, gruesome, and challenging in ways that Tarantino (who cameos) could only dream of. Sukiyaki is the story of a man with no name (Hideaki Ito), wandering into a town divided by a post-gold rush gang war that tore the town apart. Most of the residents have fled. The Red Gang and White Gang continue their violent battle for the gold they are convinced still exists. Sound familiar? It should. This is the plot of Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, which was later adapted to become Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars. Miike has re-adapted this story, using its history as an artifact of both Western and Eastern culture, to create a richly layered commentary on the appropriation of culture -- only Miike's version is far more bleak. This time, it's more difficult than ever to find your protagonist amidst the deluge of blood.

Sukiyaki Western Django - First Look Studios - Review

----

----

----

Frozen River (Dir. Courtney Hunt)

Frozen River (Dir. Courtney Hunt)

[Sony Pictures Classics]

by Katie Rolnick

When Courtney Hunt's debut feature, Frozen River hit theaters in August, we were living in a dream world. The election's energy buoyed our spirits, the economy hadn't yet revealed its depth of ruin, and we held hope that life would improve on January 20, 2009. We can still hope, but we can no longer deny the desperation of our situation -- and that makes Frozen River all the more searing. Melissa Leo, who won Best Breakthrough Actor at the Gotham Independent Film Awards (where the film took Best Feature), plays Ray Eddy, a mother of two in financial straits who resorts to smuggling immigrants across the U.S./Canadian border. Her partner-in-crime, Lila Littlefoot, is lived and breathed by Misty Upham, whose bare honesty was awarded with a Spirit Award nomination. Lila, a Native American, smuggles to earn money to regain custody of her child; to help her, she recruits Ray, whose white skin is less likely to arouse suspicion from border police. Their relationship begins under tense circumstances, an alliance of need, not generosity. As the film progresses, their characters warm to one another, slowly revealing the moral bargains a mother must sometimes make. They convince us that, if tested, we might find a way to survive with both our conscience and our families intact.

Frozen River - Sony Pictures Classics - Review

----

----

----

Man on Wire (Dir. James Marsh)

Man on Wire (Dir. James Marsh)

[Magnolia Pictures]

by Hatchet

Look up! Philippe Petit has laid down on a wire between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. He is where no person will ever be again, and there is no going any higher. For a high-wire walker, that is everything. Man on Wire, a documentary by James Marsh, skillfully chronicled Petit's quest to cross the two buildings, from the dream's inception in a drawing of the unbuilt Towers to the meticulous training, planning, and eventual completion. It is a heist movie. There is no motive besides the visceral -- to ask why is obscene, to witness is perfect beauty. Before that walk, Petit is a king in waiting. As the Towers are built, he builds. First, he walks Notre Dame, then the Sidney Harbor Bridge. These events are juxtaposed with lavish black-and-white reenactments of Petit and his team in the WTC, hiding from guards under tarps and clandestinely rigging the wire in the middle of the night. Marsh deftly balances the quest with its inspiration. His interviewees meticulously recount every detail, giving it a seemingly inflated importance, but this is where Man on Wire strives. It becomes crucial and stunning if one desires and a reckless stunt if one does not. The movie, like the event, is a gorgeous high-wire act.

Man On Wire - Magnolia Pictures - Review

----

----

----

Charlie Bartlett (Dir. Jon Poll)

Charlie Bartlett (Dir. Jon Poll)

[MGM]

by Paul Bower

Gustin Nash is a man with his finger on the pulse. For reals. His screenplay for Charlie Bartlett encapsulated much of what the Me Generation has felt about itself for decades, and we have to pat the guy on the back for nailing it so succinctly with his quirky, off-beat, and often illuminating script. The story was a timely one, featuring a 17-year-old hero fulfilling the role that his parents never could — namely, caring for mixed-up kids. In a nation where divorce and latchkey children have become the rule rather than the exception, Anton Yelchin's achingly quaint portrayal of the titular character only served to reinforce the underlying drama of parental abandonment that permeates this hilarious film. If anything, Charlie Bartlett was an effective reminder that even a touching coming-of-age story about high school(!) could still be rewarding and stimulating if carried out by capable, original hands. Not since Andrew Bujalski's Mutual Appreciation have we seen a film that treats a generation with as much compassion -- and genuinely gust-busting humor -- as this.

Charlie Bartlett - MGM

----

----

----

JCVD (Dir. Mabrouk El Mechri)

JCVD (Dir. Mabrouk El Mechri)

[Peace Arch Entertainment]

by Andy Lauer

Before Britney got all weepy and introspective on For the Record, there was... Jean Claude van Damme? In JCVD, The Muscles from Brussels lays it all out, using his own life and personal problems as fodder for this propulsive and inspired head-trip. Van Damme plays himself in a film that follows the international action star as he negotiates everyday problems like bad credit, a custody battle, and, oh yeah, a hostage situation. With its meta-narrative structure, killer action sequences, and an oddly affecting, Brechtian monologue delivered point-blank to the camera by a disarmingly vulnerable van Damme (about his childhood, drug addiction, and the price of fame), the film somehow manages to simultaneously bolster and explode the mythos that surrounds its star's celebrity. Walking a fine line between action and art film (think John Woo by way of Jean-Luc Godard), the movie actually pulls off its daring conceit, in large part because of its sincere allegiance to the man at the center of it. The biggest surprise of all, though? Van Damme can actually, sorta, kinda act. Who knew?

JCVD - Peace Arch Entertainment

----

----

----

WALL·E (Dir. Andrew Stanton)

WALL·E (Dir. Andrew Stanton)

[Disney•Pixar]

by Alex Preiss

Matching their penchant for seamless wit and execution with seemingly insurmountable scope and ambition, the savant-like folks over at Pixar pushed their ever-reliable formula to astounding new heights with WALL·E, the timeless, placeless, everything-less li'l robot love story that captured the hearts and minds of moviegoers all summer long. In other words: We knew these guys were good, but seriously? Their brilliantly synthesized use of dated pop cultural artifacts -- silent comedy, space-age gadgetry, old-fashioned romance -- to create a story that takes place hundreds of years in the future lends the film an oddly intoxicating feeling of reverse nostalgia ("future-retroism," if you will), which is why it feels like a classic even while it's still unspooling through the projector. WALL·E demonstrates the almost frightening potential of commercial cinema, were Hollywood not so concerned with remaking or adapting every semi-worthwhile film or book or play that we really didn't need to experience a second time. At the very least, let's just hope that our modern meditations on human existence need not always be framed as robot cartoon tales for children. Otherwise, the apocalyptic vision that WALL·E so boldly presents may come sooner than we think.

WALL·E - Disney•Pixar - Review

----

----

----

4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Dir. Cristian Mungiu)

4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Dir. Cristian Mungiu)

[Mobra Films]

by Amber Waves

4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days takes place over the course of 24 hours in 1987 Romania, when college students still had to buy cigarettes, birth control, and -- in extremely unfortunate cases -- abortion on the black market. Cristian Mungiu has created a bleak landscape of desperation tinged with solidarity at a time where women were forced to act on instinct (note: that time hasn't passed). Mungiu tosses sentimentality out the window, with his unflinching portrayal of two roommates (played flawlessly by Anamaria Marinca and Laura Vasiliu) as they go through the motions on the day Gabita (Vasiliu) has an abortion. What needs to be done is done. There is no discussion, no moralizing, no bullshit. From the moment Otilia (Marinca) is forced to have sex with the abortionist (played with extreme creepiness by Vlad Ivanov) to the moment when she wraps up the fetus on the bathroom floor and slides it down a garbage shoot, the two women obey only their instincts and obligation to one another. It is a friendship like no other; they have learned to live in a world without rights, and this creates a special kind of bond. But don't expect any tears. In the final scene, Otilia glances directly at the camera, directly at us, as if to ask, "What would you have done?" And the genius behind Mungiu's approach is in our answer: exactly the same thing. Because there was no other choice.

4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days - Mobra Films

----

----

----

The Class (Dir. Laurent Cantet)

The Class (Dir. Laurent Cantet)

[Sony Pictures Classics]

by David Harris

Haven't we seen this one before? A white teacher enters a class of multiethnic ruffians and wrangles them into shape in the space of two hours' screen time. Soon enough, the low-income kids are digging on John Milton and no longer trying to strangle one another. Thankfully, The Class doesn't turn out to be one of those films. Instead of resorting to forced story arcs, director Laurent Cantet (Time Out) lets his camera observe the drama of everyday situations. In this commentary on the state of public education, Cantet follows a class through a term in a junior high school, as a young teacher contends with the massive meltdown of France's burgeoning immigrant population. Winner of the Palme d'Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, The Class is exciting and realistic. It is easy to identify with the teacher's plight: everyone is overworked and no one knows quite what to do. François Bégaudeau, who stars in the film, which is in fact based on his novel about his time as a teacher, is in survival mode. When he does slip up, it is hard to hold him accountable. Anyone would crack under such conditions. Unlike the majority of films that take on similar subject matter, The Class is a rare, thoughtful statement on the current conditions of global education.

The Class - Sony Pictures Classics

----

----

----

Woman on the Beach (Dir. Hong Sang-soo)

Woman on the Beach (Dir. Hong Sang-soo)

[New Yorker Films]

by Keith Kawaii

The only way Joong-rae (Kim Seung-woo) can comprehend women is through twisted logic and the drawing of shapes. His object of affection, Moonsook, reveals she dated foreigners (apparently a taboo subject in South Korea), and Joong-rae can't bear the image. So he draws a shape for her, an amorphous, squiggly blob. This is Moonsook as she really is, he says, in all her beauty and complexity. Her experienced life is something he has, up to this point, been unable to come to terms with. No one can retain the big picture though; the shape is too unfamiliar. So Joong-rae draws three bold points of a triangle around the blob's curves. An immediately recognizable image. An image that recurs in society, and in his mind. "Like you having sex with foreigners." he says. The first point of the triangle represents Moonsook's face, the second the strangers phallus, the third is a collection of weird, porn movie positions. Joon-rae can't help but connect the dots, and we can't stop seeing the triangle. "But let's say, this point here is your happy face after those spicy rice cakes," he says. And Joong-rae marks another dot on the blob, this time forming an unfamiliar shape. "Here is your nice face worrying about a sick friend, and here is your face sitting on the toilet." He connects the dots, and their shape is awkward, but closer to the whole picture. Such is Joong-rae's struggle with reality, the only way he can catch a glimpse of Moonsook's humanity and the experience of women in general.

Woman on the Beach - New Yorker Films

----

----

----

Paranoid Park (Dir. Gus Van Sant)

Paranoid Park (Dir. Gus Van Sant)

[IFC Films]

by Chris Norton

Paranoid Park starts out as frustrating and hard to relate to as the kids it portrays, but those qualities are ultimately the film's great strength. Rarely are teenagers ever captured on screen as real, true-to-life teenagers-in-themselves, and the amateur actors that populate the film stand before the viewer in all their self-centered, awkward silence, budding before the bloom. They're posing and acting for each other, not the director or the screen. And though it might sound clichéd, we rarely see moments like this once we leave the high school halls, skate parks, and malls where Gus Van Sant's characters stalk some ultimate vision of themselves, forever out of reach. Yes, there are too many grainy, Super 8 skate-video montages. But as Alex struggles through the implications of one unthinking act of violence, his adolescent sense of tragedy is transposed into a grander frame. He is forced to account for an event finally worthy of the hormonal confusion and fear rushing through his ganglia. Bearing witness to his efforts, the viewer is given a rare chance to tap back into that long-gone feeling that no one -- no one -- could ever know what you know.

Paranoid Park - IFC Films

----

----

----

Slumdog Millionaire (Dir. Danny Boyle)

Slumdog Millionaire (Dir. Danny Boyle)

[Fox Searchlight Pictures]

by Mike Berlin

One of the strongest images Slumdog Millionaire imparts is its main character, Jamal Malik (Dev Patel), as a young child, locked in a makeshift porta-potty by his older brother. Outside, Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan (Ferroz Abbas Khan) is signing autographs for his adoring fans, and Jamal is not about to miss it — even if the only way out is down, into a poop-filled swamp below. Which brings us to the next scene, in which Jamal, covered head-to-toe in feces, wades through a gradually relenting and appalled crowd, scores the idol's autograph, leaps into the air, and screams in glory. Though somewhat inconsequential plot-wise, the scene captures what made Danny Boyle's take on one of the world's cheesiest game show franchises so affecting: It's an ecstatic, long-shot story, equal parts tragedy and triumph. Sure, the film follows three orphaned kids as they hustle and steal to survive, trying to escape child enslavers, gangsters, and all sorts of other dangers along the way. But the sense of unalienable destiny that lands Jamal in the country's most famous hot seat — paired with Boyle's knack for comedy and panache in the direst of situations — made this epic journey to the 20 million rupee question both robust and fun.

Slumdog Millionaire - Fox Searchlight Pictures - Review

----

----

----

Pineapple Express (Dir. David Gordon Green)

Pineapple Express (Dir. David Gordon Green)

[Columbia Pictures]

by Josh Dzieza

Like so many comedies produced by Judd Apatow, Pineapple Express incorporates a slew of expected elements: male bonding, orgies of destruction, Seth Rogen, shaggy dog plots that verge on feeling underdone, and women who threaten male groups that left to their own devices would use said devices to get high and to blow things up. The overall effect is a juvenile, at times misogynistic fantasy. But by making Pineapple Express a satire of action films — a genre built out of the adolescent male fantasy — Apatow was able to transform his weaknesses into strengths, or at the very least treat them from the safe distance of satire. Directed by the historically artsy David Gordon Green, Pineapple distills the Apatow comedy into a more palatable, self-aware, and therefore funnier form. But it's the rapport between Rogen, Franco, and McBride that really makes the film. Lines like Franco's dopily enthusiastic, “We can watch crazy stuff on the internet” and Rogen's sputtered, “Why are you bearing arms?” are awkward and surprising enough to be funny, yet believable and specific enough to humanize the characters. Sweetly dumb Franco and acerbic Rogen are hilarious without either offering themselves up for mockery or celebrating their own stupidity — walking a line that studio comedies rarely bother to tread.

Pineapple Express - Sony Pictures - Review

----

----

----

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father (Dir. Kurt Kuenne)

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father (Dir. Kurt Kuenne)

[Oscilloscope Pictures]

by blane

Since seeing Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father, I have been engaged in my own grassroots campaign to get everyone to see it. I have basically spent every conversation waiting for someone to say, "Seen any good movies recently?" so I can spew forth my practiced pitch about how everyone needs to see this movie because it's one of the most unique and amazing films I've ever encountered. Director Kurt Kuenne began the documentary as a way to show Zachary, the son of his murdered best friend, a little bit about the father he could never know. But the film immediately took some dark turns. The themes of the movie — life, death, happiness, grief — are oft-tread artistic territory. Somehow, despite that, Kuenne has made a documentary that, for all its heartbreak and sorrow, is life-affirming and optimistic in the way that witnessing a car crash reminds you that you're still alive and more thankful to be here than ever.

Dear Zachary - Oscilloscope Pictures - Review

----

----

----

Let The Right One In (Dir. Tomas Alfredson)

Let The Right One In (Dir. Tomas Alfredson)

[Magnolia Pictures/EFT]

by Jafarkas

It's either the most wholesome love story this year to feature graphic

dismemberment or a sly argument for the parasitic nature of love. In

Tomas Alfredson's clever twist on a familiar coming-of-age story,

12-year-old Oskar is the victim of bullies, a broken home, and his own

peculiar interests, until Eli, 12-going-on-120 with a taste for

hemoglobin, moves into his apartment complex. But it's not the

star-crossed lovers that make Alfredson's film the best of the Great

Vampire-Human Romances of 2008 (see Twilight, Alan Ball's True

Blood) or one of the year's best films in any genre; it's Alfredson's

clinical take on the subject matter. By stripping the vampire

mythology of its theatrical trappings and using the bleak landscape of

Stockholm's wintertime suburbs to his advantage, Alfredson presented

us with a simple truth -- the overwhelming nature of necessity. Then,

he contrasts this with the film's moments of subtext: a montage of

Oskar at his father's farm, interrupted by a visit from a strange

caller; Oskar peeking at Eli while she changes, turning a

coming-of-age cliché into a horror film's homage to The Crying Game;

the mystery of Eli's "father" -- could he be Oskar's predecessor?

Together, the uncertainty concerning human relationships and the

emotional and physical necessity of living leave us with no choice but

to conclude, as the film's title suggests, that love can never be more

than a gamble.

Let The Right One In - Magnolia Pictures - Review

----

----

----

Reprise (Dir. Joachim Trier)

Reprise (Dir. Joachim Trier)

[Miramax Films]

by M. Molloy

The past is always the past. Once a time is gone, it cannot be resurrected. The same goes for filmmakers; Antonioni, Bergman and Altman's styles all went to the grave with them. Filmmakers are advised to follow the late David Foster Wallace's advice to look within, rather than to, others for inspiration. The giants of cinema can never be duplicated. Or can they? What Reprise director Joachim Trier has accomplished here is nothing less than the resurrection of the French New Wave, in all the playfulness, experimentation, and precocious gravity of its high period. The story of two young, aspiring Norwegian writers, and their loves, hopes, and disappointments, Reprise is a shadowy cloudburst of a film, awash in European literature, lush blue cityscapes, taut editing, and rigidly structured yet expressive photography. With this film, Trier (Lars von's distant cousin and cinematic superior) takes his place amidst the giants of contemporary cinema. The only question that remains is, Where to next?

Reprise - Miramax Films

----

----

----

Still Life (Dir. Jia Zhang-ke)

Still Life (Dir. Jia Zhang-ke)

[New Yorker Films]

by Derek Smith

Jia Zhang-ke's chronicling of China's transition to free market capitalism continued with the playful mysteriousness of Still Life. His unique ability to weave personal stories of loss and reconciliation into the web of a city that is rapidly losing its identity and history puts this film in the rare position of capturing cultural transition not on a broad, epic scale, but on a mundane, experiential level. It was not interested as much in conveying the aftershocks of social and political change as it was in capturing that change as it occurs, a cultural shift in motion as opposed to a series of snap shots. While his previous film, The World, was perhaps more adept at stressing the effects this has had on the younger generation and in particular the difficulty of communication, Still Life more successfully produced a palpable sense of loss on a human and communal level, adding touches of the surreal to punctuate the disorienting effect of having one's hometown and national culture coldly dismantled and given a facelift in an attempt to bring it up-to-date. This tragedy is carefully balanced against the small-scale struggles of the two protagonists as they attempt to find their place amidst the confusion of this burgeoning new world. Jia's dexterous convergence of these personal and political concerns into a sustainable narrative, with more levity and humor than you might expect, accounts for the film's unique ability to be insightful and mesmerizing in even the most minor of gestures.

Still Life - New Yorker Films

----

----

----

Vicky Cristina Barcelona (Dir. Woody Allen)

Vicky Cristina Barcelona (Dir. Woody Allen)

[Mediapro]

by Dustin Luke Nelson

How does the saying go? If I had a dime for every time Woody Allen tried to "reinvent” himself... With Vicky Cristina Barcelona Allen, maybe, devolves. His first film shot on location in Spain (with only a couple of cuts back to New York) seems to have more in common with his early comedies, the classics like Annie Hall or Manhattan, than his more recent thrillers. Allen does with Vicky what he does best: turn something overly familiar and potentially cliché into something wholly fresh and distinctive. The love triangle at the center of this film begins with the friendship of two Americans, Vicky (Rebecca Hall) and Cristina (Scarlett Johansson), who, the omniscient narrator lets us know, are polar opposites. Cristina is a free spirit, who is attracted by the shameless artist and sex addict Juan Antonio (Javier Bardem). Vicky is engaged to be married, socially awkward, apprehensive, and more interested in Barcelona's museums than its party scene. Surely these descriptions could produce the most yawn-worthy film of the century, yet Allen makes this one work beautifully, twisting the clichés and coming out with a film that is pleasurably surprising. While the characters may be formulaic, the plot trajectory is anything but.

Vicky Cristina Barcelona - Mediapro - Review

----

----

----

My Winnipeg (Dir. Guy Maddin)

My Winnipeg (Dir. Guy Maddin)

[IFC Films]

by A_1000_Plateaus

Somewhat unfairly dubbed the “Canadian David Lynch,” director Guy Maddin's imagination remained maddeningly fresh in a year without much risk taking. Described by the director himself as a “docu-fantasia,” My Winnipeg connected Maddin's experimental cocktail of German Expressionism, agitprop, and playful referentiality to a slightly new style. But to reduce My Winnipeg to a semi-autobiographical account of Maddin's childhood in that city would be to miss the point. While certainly Maddin-esque in style, what made My Winnipeg unique in content was the seamless interweaving of self, memory, fantasy, and city. Throughout the film, Maddin simultaneously remembers, reports, and invents Winnipeg, his childhood memories becoming fragments of a puzzle. The payoff for us, as his audience, is the opportunity to witness the creation and dissolution of the director himself at 24 frames a second. In the end, Maddin made a film that is as much about perpetual artifice as it is about authenticity. Luckily, Maddin doesn't force us to choose one over the other.

My Winnipeg - IFC Films - Review

----

----

----

Tell No One (Dir. Guillaume Canet)

Tell No One (Dir. Guillaume Canet)

[Music Box Films]

by Evan Jordan

After he met Alfred Hitchcock, director François Truffaut was so star-struck he walked onto a frozen lake without noticing, falling right through the ice. Guillaume Canet's Tell No One, shares Truffaut's uniquely French adoration for the Master of Suspense. But Canet keeps to his own vision, avoiding the pitfalls that trip up so many thrillers. Eight years after the murder of his wife, Alexandre Beck (the stone-faced François Cluzet) receives an email saying she is alive. Scene by scene, his personal drama slowly evolves into a tangled mystery. Then, without a smirk, it breaks into a straight-up crime thriller: chases, crashes, the works. Just when everything is about to spiral out of control, Canet tightens the reigns. He keeps the pace even, giving a brilliant supporting cast time to flesh out their characters. Tied together by Cluzet's stoic energy, this cast breathes life into a labyrinthine plot. They keep us holding on through all the twists and turns. Then, when we're too tired to go on, it all pays off, not with a bang, but a whisper.

Tell No One - Music Box Films - Review

----

----

----

The Dark Knight (Dir. Christopher Nolan)

The Dark Knight (Dir. Christopher Nolan)

[Warner Bros. Pictures]

by The Friz

Since Summer 2008, The Dark Knight has grossed one of the highest U.S. box office totals ever -- second only to Titanic. While the latter revisited a tragedy nearly a century old, The Dark Knight conjured history much more recent. As a blockbuster, the film is, in some respects, more of the same: a seemingly unstoppable villain; a hero rife with self-doubt; the universe in the balance. But more so, The Dark Knight explores the potential of cathartic cinema on a national scale by revisiting the last seven years more effectively than any dramatic film thus far: the Bush years, intrusive wiretapping, the rise of the ambiguous enemy combatant, and us, culpable somewhere in the middle. When Batman stands defeated next to the smoking debris of a warehouse, ashes mingling with those of his loved one, no one mistakes the shot for anything but an analogy to Ground Zero. The film's lackluster second act -- rooted in an attempt to rationalize the anarchy up to that point -- is both the reason the film fails and the reason for its success (both with audiences and in attaining a PG-13 rating). At close, the moviegoer, most likely an American on a sunny July afternoon, is cleansed to return to normal life. That so many found it a compelling exercise is extremely telling. In what ways, I'll let you decide.

The Dark Knight - Warner Bros. Pictures

----

----

----

Snow Angels (Dir. David Gordon Green)

Snow Angels (Dir. David Gordon Green)

[Warner Independent Pictures]

by Paul Bower

We have come to expect great things from David Gordon Green. Since George Washington was released in 2000, the director has steadily piqued the interest of indie connoisseurs, and his latest film, Snow Angels, certainly justified our great expectations. Sam Rockwell and Michael Angarano were a joy to watch, and Amy Sedaris was an added bonus, taking an unusually dramatic turn in Green's small story about a small town. Olivia Thirlby, possessor of the most indie cred in Young Hollywood, broke our hearts with the understated sincerity of her performance as a nerdy highschooler crazy into -- of all things -- photography. The story was über-compelling, and the dialogue felt so consummately natural we almost forgot we were watching a movie. I think those of us who got a little scared when Green's Undertow came out last year can all breathe a collective sigh of relief. He still has it. And how.

Snow Angels - Warner Independent Pictures

----

----

----

Rachel Getting Married (Dir. Jonathan Demme)

Rachel Getting Married (Dir. Jonathan Demme)

[Sony Pictures Classics]

by M. Molloy

Although, Rachel Getting Married is best described as the story of Kim (Anne Hathaway), recently released from rehab and returned home for her sister's wedding, there is a second story here as well: the preparation for, and execution of, Rachel's wedding. Director Jonathan Demme renders both astonishing. Kim's story is all acting and characterization. Kim is a troubled woman, and her family has been deeply affected by her mental illness. Indeed, in three tumultuous days, Rachel Getting Married illuminates vast expanses of human emotion to a degree rarely seen outside (or even inside) the theater. Throughout the film, we find the camera constantly drifting away from Kim, surveying those around the bride and groom, the wedding itself, capturing what must be hundreds of extras in hundreds of beautiful little moments of intimacy, sorrow, and joy. The formal virtuosity of Jonathan Demme's direction, combined with his astonishing ability to summon a living wedding out of fiction and extras, is a wonder to behold.

Rachel Getting Married - Sony Pictures Classics - Review

----

----

----

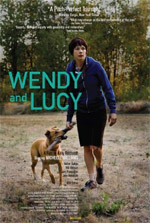

Wendy and Lucy (Dir. Kelly Reichardt)

Wendy and Lucy (Dir. Kelly Reichardt)

[Oscilloscope Pictures]

by Carla Pisarro

With a plot revolving around a hardscrabble young woman and her lost dog, Wendy and Lucy might have been relentlessly sentimental. Thankfully, director Kelly Reichardt and star Michelle Williams, collaborating seamlessly, delivered something more surprising. Wendy, whose mutt goes missing after being detained in Oregon, doesn't seem like the kind of person who'd even like dogs: she's prickly, self-contained, and, with only a few hundred dollars to her name, poor. But as embodied by the masterful Williams, Wendy is as alert and alive as her canine companion. The actress' feat is even more impressive given how little Reichardt leaks of Wendy's history. We learn next to nothing about where she's coming from or why she left, but her single-minded focus keeps us absorbed in her every move. By turns funny and sad, Wendy and Lucy is especially transfixing in light of its timely echoes. With many of us now on the verge of living hand-to-mouth, Wendy's decision to cast her lot on the prospect of finding work at an Alaskan fishery seems more pragmatic than romantic. And as funding dries up, independent filmmakers should take heart from Reichardt's example: the director and company crafted this haunting parable on a shoestring $175,000.

Wendy and Lucy - Oscilloscope Pictures - Review

----

----

Click [here to return to the 2008 Year-End Image Map]