We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

10

PC Music

PC Music x DISown Radio ft. A. G. Cook, GFOTY, Danny L Harle, Lil Data, Nu New Edition and Kane West

[PC Music/DIS Magazine; 2014]

In 2014, on a front porch in the Blue Ridge Mountains, I read DIS Magazine almost everyday through a pair of Oakley sport sunglasses. Cloud chasing and trick vaping in a faux motor-cross-style shirt with an emblazoned “No Tears” logo (a blatant appropriation of the lifestyle clothing and energy drink brand “No Fear”), I favored a particularly “apocalyptic” electronic music. This music gained ground through DIS’s prime cultural coverage and creative output during the early and mid-2010s. The sinister tremor I feel looking back on the fashion feels like my generation’s “80’s hair moment,” a mixture of nostalgia and wincing self-consciousness that hits like the syrupy tang of butterscotch vape liquid (dripped onto a modded-out lightsaber premium rig). But through the gross, sweet-smelling clouds, genius music emerged.

The cultural convergence of DIS Magazine and PC Music was an inspired cross-Atlantic synthesis. In a crass way, the collaboration felt like the coming together of allied powers, a hilarious exaggeration with all the hubris of the “special relationship” between American and British relations. Suffusing NYC’s downtown scene and fashion week demonology with the futuristic, polyglot globalism of London, the houses of Solomon Chase and A. G. Cook merged at Red Bull Studios’s gallery space in Chelsea, New York in March, 2014. The cultural influence erupted like the 1981 NYC debut of New Order playing to a No Wave-loving East Village audience at the Ukrainian National Home: an inspired urban alliance formed that changed the course of musical history.

PC Music x DISown Radio stands as the definitive statement of the PC Music oeuvre and a masterclass in the collective MIDI sound that was prosthelytized widely across the decade. This was a technological crusade that used the genetic code of pop music in a way that allowed bedroom artists everywhere to proclaim their own reciprocity with the decade’s most high-definition forms of capital. It also helped popularize the mix as a new kind of album, one that audaciously premiered and distributed completely original new music and “exclusive content” with an effortless surplus value that has become increasingly hard to locate at the close of the 2010s.

The mix had savant-level composition, it had brilliant ingenuity, it had swing. Most importantly, it had legendary ambition. Then it’s gonna be PC Music signing a deal with Columbia, then it’s gonna be GFOTY touring with Animal Collective, then it’s gonna be Danny L Harle producing for Carly Rae Jepsen, then it’s gonna be Number 1 Angel, Pop 2, and Charli. A. G. Cook was 23 years old.

09

Frank Ocean

Blonde/Endless

[Boys Don’t Cry; Def Jam; 2016]

I was blonde when I was a boy, but I am not blonde anymore.

Brunette, they say now. Dirty blonde, others begrudge. Which is to say, I know what it’s like to stand on the anonymous tile floor of another man’s bathroom, knowing I am not the man I once thought I was. And I too know what it’s like to find solace in a bottle of cheap dye, to massage a myth back into my scalp. But myths have minds of their own. The bottle calls bullshit. The dye job fucks up, turns your fragile locks rust green. And you know you can’t hide that color. The color of a bluff finally called.

So you cry in the shower. You cry in the shower because boys don’t cry, and at least in here you can admit to yourself that is not what you are. You cry because you’re alone and no one is looking. You shield your eyes because you’re alone and everybody is looking.

Our mothers tell us, “Be yourself and know that that’s good enough.” The artist f.k.a. Prince Rogers Nelson warned, “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.” By the end of 2016, Prince was dead. “Indie music” had been reduced to a tag in a Spotify algorithm. Our president was blonde, and so was Kanye. Forty-nine people had sublimated into doves on a dance floor in Orlando, and our blood could not save them.

But Christopher Breaux had juked his way out of a broken record deal, and he had bought back all of his masters. He had dipped free hands into a pool of mother's wisdom and pulled out two versions. He had dipped his hands and pulled out twooo versions, when one would have more than sufficed.

“It’s hell on earth and the city’s on fire / In hell / In hell / There’s heaven.” They told Stevie that heaven was ten zillion light years away, but for 100 minutes, Frank wound those light years so tight that we could see the other side. And when we finally saw it, who could have imagined heaven to overflow with so much tenderness, so much velocity, and such boundless waves of ecstasy? At its best, this was love.

And how far is a light year, anyway?

Physics teaches us that a light year is 300 million meters per second times 31 and a half million seconds. It’s the distance that a particle of light dances across the pages of a wall calendar. But I’ve plotted a route on the broken GPS in my parents’ old Volkswagen, and I’ve confirmed that it’s also the distance between fingers on a keyboard in December 2019 and the cold glow of a computer monitor in February 2010. A light year between us now, I think about myself at 17. I think about a boy who is still blonde and doesn’t yet know which of these two things he’ll lose first. And I remember myself, huddled around that monitor, religiously counting down 100 versions of a decade I had survived but barely even knew yet.

We need lists like we need drumbeats and albums and staircases, because they break endless things into pieces small and finite enough to wrap a body around. A light year ago, I was still blonde and endless. But even then, I sensed that someday, when the breaking finally came and I was at last made finite, maybe this music shit might give me something to wrap my body around.

It has.

In 2016, in a golden decade, in a golden country, in the midst of a golden election, Frank Ocean emerged from a shower with hair the color of failed copper and built a spiral staircase up out of this motherfucker. Some of us have been climbing that staircase ever since.

08

Charli XCX

Pop 2

[Aslylum; 2017]

I spent the decade writing about music and bodies. I came to decide that bodies and music were pretty much the same, sensuous objects that held poses and draped themselves luxuriantly in images and signs and asked to be fucked and to move alongside other objects. I tried as best I could to map beat movement onto my body, to let rhythm and repetition and yearning become a tool for change.

Kanye did his part to rip apart the seams of popular music with Yeezus, a busted-seams shriek of auto-destructing rage and futility that tore into the body of sound, but it was perhaps Charli who best brought that template to aching fullness. She, too, sliced holes into the fabric of pop histories and stitched them up with surgical precision. But where Kanye found helplessness and isolation, Charli found a future beyond words in the love-sick swirls of popular music. Collecting a dizzying cadre of collaborators — A. G. Cook, SOPHIE, CupcakKe, Pablo Vittar, Carly Rae Jepsen, and seemingly everyone else on her wavelength — Pop 2 gleefully built a sonic world where all were welcome, where identity and gender and sexuality and, yes, luxury and consumerism seemed open to all and endlessly mutable. And so each of Kim Petras’s sweet nothings urging us to “Unlock It” wrote themselves on our bodies, became ours, were a door unlocked, flung open, while we re-wrote ourselves through these pop ditties.

It’s not that Charli engaged with the tired tropes of any specific “utopia” or anything like that; no, she simply worked on the assumption that every listener is one who fucks or is longing to be fucked, and that every listener becomes the specific vocalist fucking or longing. And so she gave us countless specificities, where the identity categories lose their rigidity but maintain their milieu, culture, and possibilities. The governing principle was the feminine. The feminine was sneaky, evasive, calculating, but relentlessly pretty. It was a principle that let Mykki Blanco weaponize his feminine body and cadence as a means of conquest and overcoming, where Carly’s lovesickness was both loneliness and a tender embrace with Charli.

Affect, posture, vocal quirks, vocal fry, and vocal mutability — Charli dug into all of them and pulled out the future, in the very literal and simple sense that she used what sounded like the future and made it sound even more like the future through joyful stacking and recombination. The “future” as sonic signifier is simply an affect, but for Pop 2, that was a means to building a future, not an obstacle. Charli emptied the present-ness and the past-ness of the present and made a sound that let us make new selves and affects. She killed retromania without losing the pop lessons of the past. She took all the tools of pop, all the forward urges in it, sliced them delicately open into their constituent sonic parts, and seamlessly soldered them into a glittering series of peaks. It was a crest that carried us into new bodies, new ways of fucking, and new loves, which were instantly recognizable because they were always with us, in our emotional maps and in our musical histories — except Charli made them new. If this sounds complicated, all I mean to say is that her music sounded very, very cool and very, very shiny, and that was a perfectly good way to get us to sing along and to think about what might come next.

Pop 2 was a high. We cue up a song and let it rush into us, let it move us, let it rip us through to the future. We hit it again. Finally, the future was feminine, not female, open, pure, not without sadness, ruptured with joy and friendship; the simple pleasures of moving a body next to another body made a whole new world. We blamed it on our love because she told us we could; we loved so much that we disintegrated and became new.

Pop 2 gave us “pop 2,” a sequel, an escape that played by all the algorithmic rules of contemporary pop with such fervor that it broke through. We played in the algorithm, in the playlists, in the choruses of digits and money, said fuck it and let ourselves shift. How many times did I dance naked in the bedroom in my mutating body with a lover or a friend while Charli crooned and it felt like pop was mine again? Fuck it, love wins. Cue A. G.’s sparkling coin drop. It’s pretty; we can be pretty in whatever way we please. We’re all here, we’re all there, we’re in it.

07

Oneohtrix Point Never

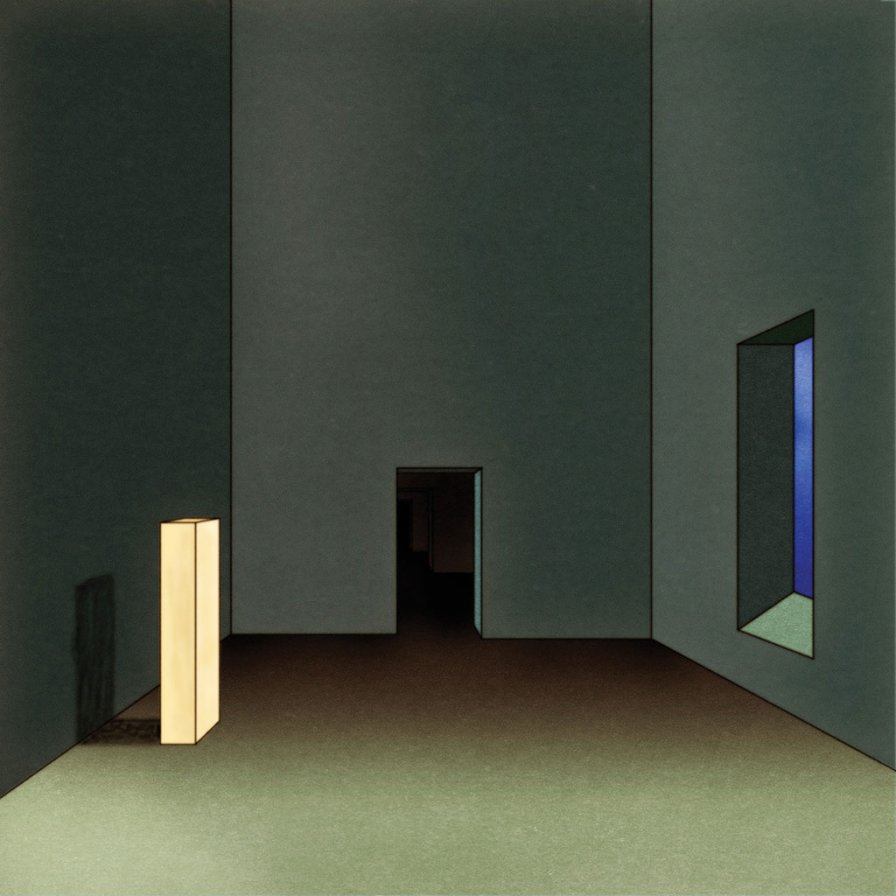

R Plus Seven

[Warp; 2013]

There are 10 pieces here which open up quite unexpected vistas of the richness of realistic effect that may be obtained with sound. Never, for example, has the northern daylight in our apartments been rendered with the realistic power contained in “Boring Angel.” Never has the seething life of the street, the teeming of the crowd on the asphalt and of vehicles on the roadway, the waving of the trees on the boulevard in dust and light, the elusiveness, the transience, the immediacy of movement been captured and fixed in all its prodigious fluidity as it is in the extraordinary and marvelous “Americans.” From a distance, this stream of life (“Inside World”), this great shimmering of light and shade (“Problem Areas”), spangled with brighter light and stronger shade (“Zebra”), must be saluted as a masterpiece. As you approach, everything vanishes; all that remains is an indecipherable chaos (“Chrome Country”). Clearly, this is not the ultimate statement of art in general, nor of this art in particular. But what a clarion call for those who have a subtle ear to hear, and how far it carries into the future!

These words, I admit, are not my own, but modified excerpts from a translation of “Le plein air, Exposition du boulevard des Capucines” by Ernest Chesneau, an 1874 review of the First Impressionist Exhibition. But this doesn’t make them any less true of R Plus Seven, Daniel Lopatin’s 21st-century “impressionist” masterpiece. It would be a fair interrogation that using words written over 100 years ago in a blurb about an album less than 10 years old is ahistorical, that it sours any profession that Lopatin is terribly revolutionary. But if Oneohtrix Point Never is as “intransigent” as Manet, as “dazzling” as Degas, as intimate as Renoir, it is not out of mere imitation; rather, without directly referencing anything (but recalling everything), OPN’s output this past decade incidentally shared with these early dissidents of form not a distinct goal, but a proclivity for capturing “Still Life” from unusual angles, shedding light, as it were, along forgotten windowsills, exposing that “sinister” beauty that lurks in every nook and cranny of our crappy lives like floating dust that only refraction can reveal.

Later on in Chesneau’s review, he worries that Manet has opened a door for “inept painters” and “laggards;” he warns that embracing this trend invites “the kiss of death.” People would later say similar things about vaporwave, about what Lopatin was doing with arpeggiators and sequencers and samples of infomercials, but it was R Plus Seven that exhibited what really made early critics of “Impressionism” wary of backing a new school: that is, what had emerged from realism’s ashes was threateningly beautiful, a phoenix that ignited our guilt-wracked hearts before rekindling itself inside us as awe. Its magnanimity enveloped us entirely, inspired bloated words and eccojams, and ultimately freed us all from criticism’s clammy, historicizing, pen-fondling hands. No wonder critics were scared of it. “And how far it carries into the future!” Even grander how it rendered time right off its bones. We would never be the same again.

06

Macintosh Plus

Floral Shoppe

[Beer on the Rug; 2011]

Very few records come to define a genre in the way that Floral Shoppe has. For many of us here at Tiny Mix Tapes, the first part of the decade was spent listening to and thinking about vaporwave. And in the years since its original release in December 2011, Floral Shoppe has steadily become the genre’s best-known document, vastly exceeding what any of us expected of it — of any vaporwave, in fact — even as we were championing it.

Floral Shoppe was nothing short of a phenomenon. By 2018, its most famous track “リサフランク420 / 現代のコンピュー” (“Lisa Frank 420 / Modern Computing”) had amassed more than 40 million views on YouTube before being removed, apparently at the request of Sony, owners of that famous Diana Ross sample. The track was quickly re-upped, of course, and is currently sitting on a cool 8 million. These are simply not the kinds of numbers normally achieved by experimental or underground artists. Nothing by James Ferraro, Oneohtrix Point Never, Holly Herndon, SOPHIE, Laurel Halo, or Mount Eerie — not even Burial — gets remotely close. Not on YouTube anyway.

What’s striking with hindsight is that when vaporwave “landed” in 2012, part of the attraction was the presumed impossibility of it ever going mainstream. Vaporwave, we said, was democratic at the level of production not reception. Because its appeal was always conceptual at least as much as it was sonic, because it relied so heavily on appropriation, because in the most radical cases it was in fact nothing but an act of appropriation (such that the comparisons with plunderphonics and other sample-based musics missed the mark), it just never seemed like the kind of genre that would attract much of an audience outside the communities making and writing about it.

How wrong we were. Floral Shoppe confounded expectations because it married vaporwave’s characteristic critical distance with a more direct sensual pleasure in a way that few others managed or attempted. Compared with Ramona Xavier’s other releases under the New Dreams Ltd. faux-corporate umbrella — as 情報デスクVIRTUAL, Laserdisc Visions, PrismCorp Virtual Enterprises, and Sacred Tapestry — Floral Shoppe was much easier on the ears. But there was a paradox here. Tracks like “ODYSSEUSこう岩寺「OUTDOOR MALL」” by 情報デスクVIRTUAL or “By Design” by INTERNET CLUB were so “easy on the ears” they were grotesque. In fact, the deeper vaporwave dredged muzak and easy listening’s frictionless depths — i.e., the less the artist-corporation revealed themselves at the level of production — the harder it seemed to listen, such that the critical work required to keep tuning in was always also a kind of masochism. Vaporwave’s pleasure was often perverse.

Not so with Floral Shoppe. The grooves it sampled — especially from Diana Ross, Sade and Pages’ “You Need a Hero” — were all undeniable. And when the record turned to the German smooth-jazz/synth duo Dancing Fantasy in its second half… well, it turns out that Dancing Fantasy were in fact pretty good! Whatever else she may be, Macintosh Plus was an impeccable (digital) crate-digger. And the production, light as it may be, is artful throughout. The artist is present. Unlike other artifacts from this era of vaporwave, this record always felt composed.

Floral Shoppe is not vaporwave’s most radical release. Even Xavier has sometimes questioned its disproportionate success. Like pop art or rave before it, one of vaporwave’s more important interventions was precisely to put into question both the cult of artistry that demands and is sustained by lists like this one and its complicity with the affective economies of capital. But these structures are desperately hard to dislodge, doomed to return like some pitched-down Diana Ross: “It’s all in your head / It’s all in your head,” looping back again and again, each time a little less stable, before finally breaking down altogether.

With the second iteration of 100%ElectroniCON already behind us and as the scene moves increasingly from URL to IRL, I can’t help but wonder whether vaporwave’s apparent success has depended on it becoming a “sound” or “style” in a way that betrays the more radical possibilities that seemed available on its arrival. Nevertheless, Floral Shoppe served as a metonym for and gateway into a genre that — from its design a e s t h e t i c to its queer/trans roots to its unexpected and much-contested forking into genres like fashwave and trumpwave — proved surprisingly resilient across the decade and continues to defy expectations.

05

DJ Rashad

Just A Taste Vol. 1

[Ghettophiles; 2011]

Bear with me [one last time]: Mr P once told me that Mortal Kombat II helped him discover the internet, because of

SMASH CUT TO 1994,,,,

,,,,And it’s Keith’s ninth birthday at Putt Putt Golf. Unlimited arcade tokens in an infinite screen-to-game ratio. Mortal Kombat II popping off in the back corner. Enter: a new eternal battle of life.

The precedent DJ Rashad set in Just A Taste Vol. 1 started a whole new battle.

Everything Mr P wrote about DJ Rashad became literature. And in my Fusion, I chose to boil it all down to Just A Taste Vol. 1. This was a new war zone for listening.

Most times, footwork after Just A Taste Vol. 1 felt like imitations. Few times, footwork after Just A Taste Vol. 1 matched various bits of it, but never in total. At best, Rashad’s footwork post-Just A Taste Vol. 1 was doing his best LucasArts impression: reworking the masterpieces for international audiences.

But Just A Taste Vol. 1 was the genesis to this decade’s evolution of recorded footwork, and listeners couldn’t help but Pledge all floors, buffing ‘em with a pair of fresh socks

You’ve no idea what Mr P has to go through to edit my content for this website [editor’s note: here’s just a taste]. I only try to be THE most extra in my TMT posts, because I compete with Mr P. Whether I was trying to out-weird, out-extra, or out-genre him in content, Just A Taste Vol. 1 was the initial adrenaline rush that he provided (in writing and recommendation of flavor) that made me go all out. All this content

website [editor’s note: here’s just a taste]. I only try to be THE most extra in my TMT posts, because I compete with Mr P. Whether I was trying to out-weird, out-extra, or out-genre him in content, Just A Taste Vol. 1 was the initial adrenaline rush that he provided (in writing and recommendation of flavor) that made me go all out. All this content  has always just been a silly afterthought of who can waste more time in their life. Or secret letters of admiration. Or testing Mr P with literal nonsense I deem intentional. I am eternally in battle with Mr P because of Just A Taste Vol. 1.

has always just been a silly afterthought of who can waste more time in their life. Or secret letters of admiration. Or testing Mr P with literal nonsense I deem intentional. I am eternally in battle with Mr P because of Just A Taste Vol. 1.

DJ Rashad set an expectation for nearly all electronic music in the past 10 years when Just A Taste Vol. 1 was released. Footwork found life outside Chicago. Club music expanded, vibrantly. Sound collage became rhythmically glitched. The line between DJ and producer continued to blur. DJ Rashad planted seeds this decade that haven’t even begun to sprout. The hybrid continues to mix genomes with Just A Taste Vol. 1.

04

SOPHIE

OIL OF EVERY PEARL’S UN-INSIDES

[Future Classic; 2018]

We exist under a regime that forgets — because it’s afraid of — the flesh. Under this regime, human bodies are assemblages of symbols that fit together & interrelate not unlike the component parts of a machine. Indeed, they’re subjects in a system of normative biopolitical imperatives — quite often enshrined in the Law — which would conduct conduct to maximize the productivity of our bodies. It’s not just self-help books & motivational speakers; these are just symptoms of a discourse that alienates us from our bodies, constructing the human as above & beyond nature.

Within this discourse, each appendage fulfills a particular role, often determined by one’s gender assigned at birth. HEAD represents reason, which sets us apart from “nature” (i.e., the non-human) & is seen as the epicenter of the human being; it’s no coincidence that reason is constructed as the domain of men. HANDS are the conduit through which we effect action out in the world, reflecting a narrow understanding of “action” in terms of work, which is masculinized by the representation of physical power in the fist. HEART, of course, hosts the human capacity for Love, yet is often seen as encumbrance rather than asset, despite our extreme altruism underwriting assertions of human exceptionalism — a conception surely buttressed by misogynistic tropes of women overly moved by emotions.

Strangely, it’s the genitals — repositories of sexuality & desire — that determine how hegemonic discourse imagines & constructs the rest of the body. In a discursive sense, the genitals are the appendages nearest to the flesh; sexual desire, indifferent to the attributes that make us human, “grounds” us through its reverence to the flesh, namely via the “private parts,” which, in fact, cast quite a wide shadow over the public sphere. Hence, the regime’s fear of the flesh ultimately zeroes in & flares around the genitals, through which the flesh draws attention to itself, abating the distinct attributes of our “humanity” & undoing the estrangement from the flesh that enables the regime to optimize the body & maximize productivity. Sexual repression is therefore the regime’s way to escape that to which we are inevitably drawn back.

Here we arrive at the threat of the queer body, which doesn’t choose the object of its desire or identify according to the dichotomies of the regime’s imposition. Of course, it’s no coincidence that queerphobic voices constantly assert that sexual expression is a choice; that is, that reason can trump it. Because, as far as the regime is concerned, the queer body is a terrifying example of the failure of reason, of the “human” succumbing to the flesh, to animality, to nature.

Among many, many other things, OIL OF EVERY PEARL’S UN-INSIDES was a celebration of the flesh, which the regime ensures remains for the queer person a significant source of dysphoria. Even further, it was a reclamation of the body & its doings. SOPHIE was preoccupied not only with the desires of the flesh — although that was in there (“Ponyboy”) — but with the possibility of its deconstruction & reassembly (“Faceshopping,” “Immaterial”). Not to mention, by pairing her subversive discourse with production that shifted between industrial plasticity & bubblegum pop, SOPHIE disaggregated the correlations of strength-masculinity & frivolity-femininity. If the regime sought to conduct conduct, SOPHIE’s was an exercise in misconduct. Which is to say that, this decade, SOPHIE was the regime’s worst nightmare.

03

Kanye West

Yeezus

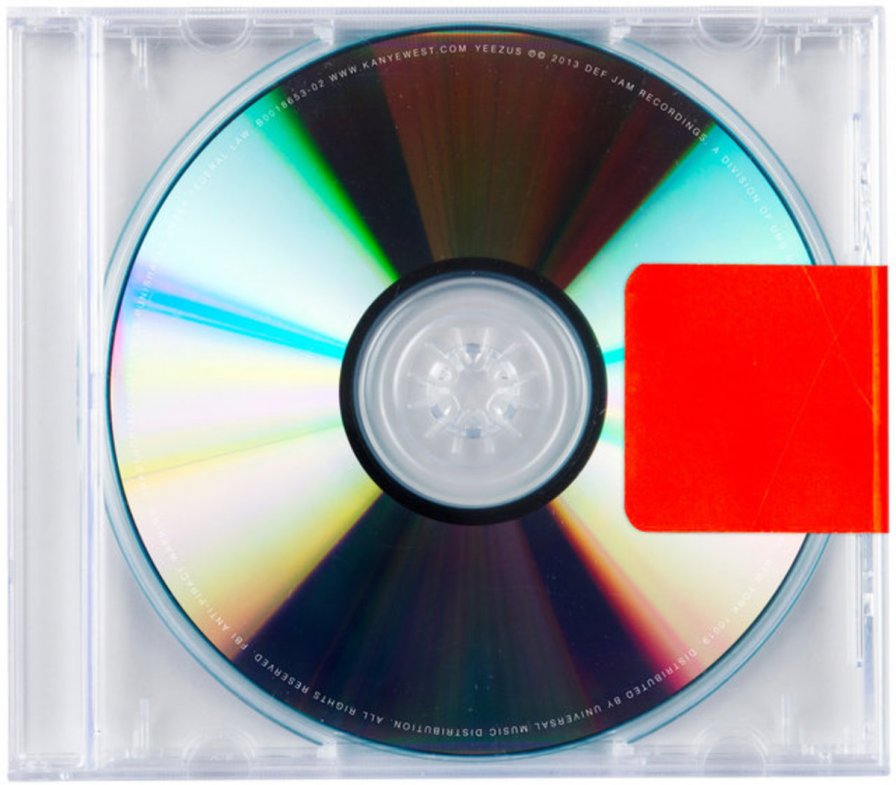

[Def Jam/Roc-A-Fella; 2013]

Uh-huh, honey. In its own particular way, Yeezus was where the decade in Kanye began and ended. It zeroed the opacity and goodwill generated by My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, clearing the site for every last provocation that would follow hereafter; it was built on the scaffolding of former glories (most notably the urges and inclinations of Cruel Summer), before being gradually torn down bit by bit, as Ye turned his iconoclastic tendencies upon himself and his image. To be sure, even as we spent good chunks of the decade in adoration, revulsion, or downright indifference toward Kanye West, Yeezus was evidently one of the shining beacons of the 2010s according to Tiny Mix Tapes. Both upon its release and in our present moment(s), it felt, still feels, like a particularly enigmatic entry in the catalog of one of popular music’s most prominent enigmas, Bound up as it was in second guesses and internal logics. And yet, it truly stood apart in Kanye’s oeuvre in its total commitment to transparency and in its clarity of vision; a forthcoming, completely airtight expression of intent that now stands as the prism through which his life and work is best examined.

Really, Yeezus has heretofore said all it has needed to say of itself. We can safely presume the relatively quick turnaround in its recording, including some 11th-hour tinkering by Rick Rubin, as well as its austere palette pace the luxurious MBDTF, because that’s what it sounded like: triumphantly, pointedly minimal in its construction, engineered for a fullness of affect in a heartless world; the sui generis anti-masterpiece, encased in a plastic outer that featured little more than a lone, dispassionate red square for identification. On the mic, Ye was alternately on acerbic form — not deigning to niceties (certainly not to basic decency), not cowing to the overbearing arm of corporate America — and in a more measured, lucid mode; a kenotic God pared down to his rawest base instincts. This was hardly the first time Kanye had given himself pause, but the tussle with himself and/or his demons was more pronounced than ever on Yeezus, a monster that would come alive again, again, and again throughout the slippage of the decade. Moreover, it exposed the dangers and pitfalls of projecting an entire philosophico-politico worldview onto the biggest rock star on the planet, a purported billionaire no less; this isn’t to disavow both the latent and overt politicking on the album, given Kanye’s continued commitment to social justice, but rather to highlight the Void at the heart of culture, of celebrity, and of capital, a Void that Yeezus bore full witness to. If Kanye sounded at the peak of his powers here, it was patently lonely at the top.

Oh, yeah, the music. One could write entire paragraphs, theses even, dissecting every last skree and skronk between the beats (or lack thereof) that make up the architecture of Yeezus. From that initial blast of distorted warehouse acid, right through to the stark, unvarnished sampling from No I.D. that closed proceedings, the album operated with a contrarian logic that nevertheless excited and reviled; it really did “pop a wheelie on the zeitgeist,” so much so that no other major label rapper dared to make a return to its indignant pith. It was a melting pot — of voices, statures, and sonics — that gave Ye the munitions to craft some extraordinarily memorable (read: memeable) set-pieces. Isolated flashes of brilliance include: the gospel flip that punctured “On Sight,” the Malefic-in-a-coffin screaming and gasping in the Justin Vernon-featuring coda of “I Am A God,” and “Guilt Trip’s” effervescent synth work, wafting atop hollowed-out kits and terse sub-bass, to reductively pick out but a few. Elsewhere, entire tracks stole the show, as Kanye cornered sports advertising forevermore with a genuine anthem (“Black Skinhead”), desecrated “Strange Fruit” by way of TNGHT histrionics (“Blood on the Leaves”), and best approximated what Tricia Rose or Robert Beckford term “Black noise” in utterly indomitable style and phrase (“New Slaves”).

The devil, whose apparition apparently defined and informed an entire life’s work until very recently (“I been workin’ for ya my whole life”), was well and truly in the stitching of Yeezus. It seemed, for example, more than coincidental that Yeezy’s auto-tuned voice was typically preserved for his most cogent interrogations of Self, as on “Blood on the Leaves” and “Guilt Trip,” as if he could only humanize himself by way of effect and affect. A number of years, cold(est) winters, countless listens down the line from the 256kbps leak that still resides on my iTunes, and Yeezus can only continue to delight, to intrigue. Kanye West rarely made overtures to anyone or anything in the 2010s, but this was one of them: a properly beautiful, dark, and twisted fantasy that convulsed between our fried synapses and rattled us to the core; the zenith of a stratospheric career, the twilight of Kanye’s fading star.

02

Dean Blunt and Inga Copeland

Black Is Beautiful

[Hyperdub; 2012]

Black Is Beautiful, one of a few crests in the imposing Hype Williams wave of the 2010s, was recorded and released in a year of uncertain but likely apocalypse, and when held together in the mind on a list like this, it still judders and quakes with the possibility. Somewhere between career culmination and business as usual, Dean and Inga and co.’s final major offering maintained their day 1 promise of a certain form of honesty-if-nothing-else (a bizarre claim from such skilled and relentless mythmakers, but for fans of the group the very essence of what could be delivered), this time possessing a strangely charged sense of purpose, a series of movements in crisis that squeezed into any number of musical molds of the day while only ever sounding like themselves — whatever that was — “in-betweenness” somehow honed to a fine point.

The obvious stunners were the result of a locked-in and keyed-up pop sensibility in full flower, production miracles made more so in their permanent “demo” form, but the rest of the album could almost be tasted with enough concentration — interludes that reintroduced themselves on repeat listens as main tracks, exploratory and unpredictable to the very next note even as they traced the edge of recognizability; melodies so curious that the instruments producing them quickly slid out of mental view, only sub-bass and sensation left in deep (red) focus. There was a constant profundity to it all, even sometimes a profound stupidity (try to make it through “14’s” chicken-dance dead end with a straight face). Fairly new genres developments were “played,” like they’d already been drained by time, now just rows of atmospheres to rent and remodel. “History [was] inhaled and exhaled,” more than an accretion of what came before, neither in thrall to the past nor ignorant of its lasting afterimage, only a generously employed soft focus keeping everything from turning upside down.

Much has been made of Dean and Inga’s endless trapdoors and obfuscation; not nearly enough has been written about the rarity of their work ethic, their real-time risk-taking, their determination not to close themselves off from the world. In doing so, they commanded an unmatched emotionalism and intuition, fostering a kind of dignity in chaos. That music like Black Is Beautiful exists at all is a serious blessing.

01 (∞)

Chuck Person

Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1

[The Curatorial Club; 2010]

Last night, I dreamed I made the perfect eccojam. You were there, and you were there, and you were there, and you, and you, and you were there, and you were there, and you, and you, and you were there, and you were there too.

What were your favorite 50-(something) minutes of the decade?

It took a long time to get here, a lot of scrolling, at least. And after 10 years, we’re finally wise enough to make the wrong pick for our favorite release of the decade. A pick that could melt in the sun if you left it out on the passenger seat. Can you smile about it? Nod knowingly, maybe, happy. Or yawn. Did this wave crash predictably?

I believe The Caretaker or DJ Rashad or Grouper or Laurel Halo could very easily occupy this position, though I can hear in Eccojams variations of each of these artists’ adaptations to the physical constraints of time. I also believe our staff wishlist of personal favorites from the 2010s might’ve (and should’ve) effectively made this choice obsolete! But it’s a choice “we” made, and it’s one I believe in, like I believe in ghosts.

“Be real, it doesn’t matter anyway/ No, it’s just too little, too late/ Be real, it doesn’t matter anyway/ No, it’s just too little, too late”

In some respects, this list meant nothing. In others, it meant the world, to the community behind Tiny Mix Tapes, to me personally, and hopefully to you.

I believe Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1 is our #1 not because nostalgia won our decade, whether reflective or restorative. We did not spend our decade drowning in the deeps of our miserable desire for endless summer nights and the eternal loop (for nothing). We haven’t all of a sudden been gifted a deeper appreciation for the afterglowing lineage of the Eccojams limited cassette release, its belonging to the purer internet, or even the premature and constant death of vaporwave.

I believe Eccojams is our #1 because we at Tiny Mix Tapes couldn’t get enough of music. And Eccojams, of music, begat more music.

Made music in us, made us make music.

Made us listen better. With every Pang and its Mutant child of rage, every mixtape sequel, every deleted SoundCloud track, every Liz Harris moniker, Instagram story snippets, Dean Blunt — through music, we learned how to love this decade.

How much of that time was spent wandering the internet? It’s hard to imagine wanderlust about the frontier internet anymore; it has been so assumed into everyday life as to make that observation null, but in 2010, when Eccojams was released, there was a little more magnetism in the links, before torrents trickled into streams, maybe a searching that had been a little less, say, streamlined for easy listening.

And so a reworking of easy-listening pop music sounded a special kind of project, not quite They Live glasses, but at least a message in a bottle: “Hey, listen!”

The most popular “lo-fi beats” background-listening livestream’s artwork is a swipe from Whisper of the Heart, one of my favorite movies, its original title literally translated as, “If you listen closely.”

Maybe Eccojams was our favorite because we wanted to save it from interpretation that would reduce it to the one reading — the understanding that it was a performatively unflattering and grotesque reflection of broken culture. We’d heard more than that. We heard in it instructions, lesson plans, accidents, tools, and effects. We heard a hundred different ways to say the same thing, a thousand ways to listen. As much as Eccojams was about casting a revelatory light on the material circumstances of this decade, it was also about our audition: our fidelity to hearing. To listening, which is the beginning of community, of creation.

“Did you make this?”

If you weren’t paying attention, or toiling away on something else, you could mistake anyone’s eccojam for one of Chuck Person’s. The creative process was an algorithm, the Swedish directions for a remembering-machine. It wasn’t a genre of classical nuance; it was about tapping into a feeling, drawing from your own archive, laying bare the beautiful abundance of your “hidden resources.” Like folk music.

In a Reddit AMA, Lopatin referred to eccojams as folk music, and in doing so suggested a hybridization of the polar organizations of composition laid out in Brian Eno’s “Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts.” Eno references the “hidden resource” of folk music, which are the valuable idiosyncrasies of the individual performer, as compared to some classical music’s more rigid commitment to algorithmic formality that bows to hierarchical value systems.

Eccojams were a charged program, then, in their strict/open process: run a looped sample of radio music through a simple filter. The contradiction was how this rigidity transformed our ability to appreciate the smallest moments of MOR songs, make them as unnerving or thrilling as laying in the middle of the road. There was more than you thought possible, and now nothing felt impossible.

Ultimately, we arrived at the not-always-forgone conclusion that “changing environments require adaptive organisms.” Another not-always-foregone conclusion: if you find yourself overly dependent on a coping mechanism, it must not be working well enough anymore.

This was a decade that pressured us to play it cool and/or self-manifest as Homo superior. Nowhere could this desperate adaptation be seen like it was in memes. By virtue of its archive and fried architecture, Eccojams became the premier musical representative for meme culture — stacking levels of awareness, repetition as the medium, the message unfolding forever, like the scroll of The Caretaker, an edited collage of Pablo, a language of infinite collaborative possibilities, of mutually unknowing interconnectivity via parasitic networks, self-modifying code, and lairs of referential knowledge — all drawing from the most popular well, the well of loneliness.

And so, vaporwave was a genre and an internet meme. Chuck Person wasn’t a sole author.

“Where’d you get that information from (from)?/ Where’d you get that information from (from)?”

Before Eccojams, there was sunsetcorp, Daniel Lopatin’s YouTube channel channeling YouTube surfing, which included the best-ever eccojam, “END OF LIFE ENTERTAINMENT SCENARIO #1,” to be found nowhere and everywhere on this release. These media meditations prefigured the more unsigned emotional rummaging of Replica, which was our favorite album of 2011. Yet there was even more to love here, in Eccojams, maybe because it seemed to be made with us in mind, the way a friend who’s only a couple steps ahead of you can recommend affordable therapy, or provide a listening ear. What a gift, to be able to let go of what doesn’t work, and to hear something that does.

What are some songs that you love, that you could share with your friends? What makes you want to make an eccojam? What are some things you don’t like about eccojams?

These were labors of love, tracing the footsteps of the Screwtapes. As in DJ Screw’s chopped-and-screwed mixes, there was the idea that these song choices might be invitationals, appeals to recognition that get you thinking of the potential in songs, your own potential. That Daniel Lopatin modeled Eccojams, and indeed took his moniker, after a soft-rock radio station, Magic 106.7, speaks to his sentimental attachment to this music. Realizing this project is about channeling a connection to the radio, that this is not only a restaging of cultural detritus to reflect the heartbroken smoothness of capital and mass culture, meant the world to me, and I think you could hear it all along.

Chuck Person was a sincere YouTube commenter from 2012, an avatar that revoked the “supremacy of the original over the derived,” to invoke Adorno’s precious contempt for the impossibility of genuineness, writing about bourgeois moral gold. This love opened the door to so many possibilities for the derivative, the incidental, the illegitimate, the usurpers. I believe these songs could wear their bent-edge color Xerox unoriginality on their sleeves without hating themselves, without being statement pieces, perhaps just posing in front of the mirror, wearing themselves out like makeup or magnetic tape. Feeling themselves.

It’s not mere critique, it’s a love letter. It’s so head over heels, it repeats itself.

Like history. Getting not funny: a man who has somehow managed to corrupt the grossest seat ever, utter ecological catastrophe, multibillionaire space races, police-state terrorism — it’s the same Billy Joel or New Radicals or whoever song — echoes and continuities of crises from decades past, no less important or crucial. In fact, with increasing, additive importance, we’re in crisis mode — indeed, a crisis ordinary. It would be easier and not unsurprising to seek refuge in exhaustion, nostalgia, denial.

We looked at the brokenness of the decade, itself a post in a feed, though riven by towering fixtures and ideological fixity, and we heard the relentless, un-unchanging repetition of Eccojams and couldn’t help but remember, in the words of Marvin Lin (our Mr P), writing on Eccojams for 33⅓, that “nothing is truly fixed and everything is ripe for transformation.”

We heard a tension for the decade: the radical possibilities of the ever-unfolding and rapturously enfolding loop, and the conservative impulse to hole up in exactly what we already knew we loved and preserve it forever at any cost.

“I (I) know (know) that (that) door (door)/ That shuts (shuts) just (just) before (before)”

When I was at my worst, I loved riding out the spins. The looping of Eccojams made sense, in the way ad nauseum and ad infinitum could feel part and parcel of going in and going out and going in and going out.

It was Eccojams that I stuck my head in, and it was eccojams that pulled me through. In the lamentable years (years of my life, years of this decade) that I spent alienating myself from those I loved most with my drinking, I could at least attach myself to the feeling of memory, of missed connections, of another chance — somewhere on the horizon was the sunrise, where my salvation lied, at the edge of tomorrow.

It was Zech who introduced me to OPN (then pronounced, “Own-ee-oh-trix”) and Eric Copeland and Brahms and all manner of other shit, and it was in his room where we would just sit and listen. And drink, yes, with abandon. His bedroom had a door in each of its four walls, one to the kitchen, one to the bathroom, one to his roommate’s, and one to the street. I spent many nights trying to convince him how if you stood at the center of the room and spun 90 degrees repeatedly, you would be faced with the exact same wall at each turn. Over and over. I was not listening to myself. I was obviously not paying close enough attention. But I hoped he would get the gist. It was Zech who told me to get a grip.

Advice for the young at heart, soon you will be older.

When not much else obviously presented itself as an option, eccojams were a coping mechanism with few moving parts, little mystery, yet somehow still full of little mysteries.

Like years later. Years after throwing up on Zech’s floor and falling asleep in doorways, waking up in a hospital hallway the morning after my patron saint’s holiday, only to be told I wasn’t the only one, hours after I’d been listening to “Only One.”

A salve for the repetition of addiction found in the repetition of loops, these loops I made not only out of self-destructive habit, but prayerfully, with half-empty optimism, for my own ears, for no good reason. Eventually, I started listening. Actively listening.

Daniel Lopatin was a good teacher, in this sense, thanks to humility. Before the worldbuilding and world premieres, when he was clothed in Chuck Person, there was an intentional practice, founded in the belief that rudimentary tools and a simple ritual could create cosmopoetic compossibilities for listening, which instilled in us at Tiny Mix Tapes the belief that these fucked-up little songs could become gateways.

Door to another, door to another, door to another, door to another, door to another.

As soon as you’re listening for the echoing words in between, listening to “B1,” when that parenthetical turns into a portal, you find the door in the back of the wardrobe, and there you find not yourself, but yourself-listening for the sweet relief of that bass swell, the cooing hum that reliably zooms into the mix before “never,” the softly winding pan-synth that uncoils around “proud” — artificially bound by your relation to the music, into presence.

In the presence of each other, we found no stickier drama than the planetary entanglement of our relationships, coincidentally or however bound we found each other in the tidal-locked orbit of Tiny Mix Tapes, where we had your readership, and more and more writers who weren’t writers, but historians and web designers and teachers and parents and students and friends.

Our listening brought us closer together, into the belief that through listening and the music itself, we wouldn’t achieve actualization or revolution, but that if we listened closely, we would become unafraid and nothing would be unthinkable. Maybe we’d be sensitized to the possibility of each release, remembering that just about anything could make us exclaim, EUREKA! And then we’d repeat ourselves, listening for the call and response of our love, the deep in me calling the deep in you, Side A, Side B.

We learned a lot from a few seconds of that song, Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel, now nothing more or less than Chuck Person, a mantra and a close read, a wave of sound crashing whatever meaning was transmitted, now transmuted into the choppiness of the sea itself, like the water covers the ocean.

So Eccojams is a stand-in, for everyone and everything, the memories that looped in your head, the memories you wish did, the songs you dreamed of making, the times and time you wish you had.

A part of me wanted to write this whole thing without mentioning Daniel Lopatin at all. This release belongs, after all, to YouTube uploaders, Audacity users, and Chuck Person: carelessly thrown together, a cut of meat used for stewing, an individual, one of the triune components of God.

No goodbyes, no goodbyes, just hellos, just hellos.

In the fade-out song on Eccojams Side B, a resplendently remade loop of “Woman In Chains” by Tears For Fears, the shimmer (a freaky chorus effect, I think) keeps approaching and receding over the sample, never not there in the mix, until it overtakes the words, transforming the song and the tape into the glow. The loop opens up into a slow fadeout that transitions into your life’s sounds (as long as you turn off autoplay).

In the last song, maybe you felt the rush of recognition, or maybe you felt held by the sureness of the synth returning again and again, and, if the song connected, if Chuck Person echoed your feelings, you heard your heart beating.

We couldn’t have made it this decade without you. I believe that’s why Eccojams is our favorite.

Our favorite music release of the decade is something you could’ve made.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series