We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

Mass consensus is a weird phenomenon. It suggests that what people share is more valuable than what each of us keeps close; it’s a Campbellian reflex that we haven’t shaken out of what we do here (primarily, tell you what we like and what we don’t.) Then again, perhaps this tendency, of seeing your joy reflected in some other body’s curled lips or bobbing head or twisting waist, demonstrates a rare kind of empathy that difference has difficulty climbing inside of. Perhaps we revel in shared intrigue, because it’s simply how we relate with one another, how we make friends or navigate space or get jobs; perhaps all of that is still important and worth discussing around a rectangle. Perhaps, still, it’s just how our faulty algorithms function. But y’all know that we like other shit too, right? That some of us don’t love James Ferraro or that more than a few of us still love Taylor Swift (both absent from this list)?

Every year around this time, there is a discussion among writers here at TMT (and readers too, I imagine) about what list-making really means, functionally and politically. We’ve been intentional about calling our lists “favorites,” subtly calling out publications that still publish lists like “Best Albums” or “Top Tracks,” but what does “favorite” mean? And how do we individually arrive at what we “favor?” How should we? How shouldn’t we? What does it mean when nobody’s Number 1 Album ends up our Number 1 Favorite or when one Flame outshines like a hundred other brilliant hues or when our favorite hits are made by shitty people or when perfect 5/5 albums miss our lists entirely or when modern classics drop in late December or when review & blurb completely clash or when NEARLY (with exceptional exceptions) every AOTY these past 10 years was crafted by a man?

These conversations that result in content are messy; if you’ve ever read a Tiny Mix Tapes list this decade, you can see these stains and holes all over. This is a list of stains and holes that missed our Main List of stains and holes. Some of them, familiar, remained preserved in time, growing sideways where they surface here with new perspective (Dawn Richard, Holly Herndon, Pharmakon); some were early-decade decadents that smoldered softly in our hearts as glitter burned around us (Sleigh Bells, WU LYF, Broken Water); some arrived here forgotten champions, untelevised or overshadowed (RP Boo, Niño de Elche); some were deeper cuts that averages just couldn’t crack (Motion Sickness of Time Travel, Michael Pisaro).

And yet, none of these were tangent, but embodied in our heart-shaped boxes where we keep our drugs and feelings, not print-outs of Pazz & Jop lists and safe MOR recommendations from our coworkers. These expressions are what shaped us when we went home searching for a laugh (The Lonely Island) or an “Audience of One;” they’re what made us feel unique when we needed that kind of confidence in self over solidarity. Still, in their mere materiality, all lists can feel deceiving or alienating or cheap or obvious or ostentatious or exclusive. This particular one was compiled from writers’ individual lists, and though it boasts no underlying consensus or narrative or corrective agenda, it’s still just a list. As such, it won’t change how lists are read or how they’re made, but I can assure you that our labor in presenting it here was pure (x) love for blabbering about what(ever else) got us through these past 10 heavy-ass years, and after enduring a month of torrential wordstorms about why stuff we already hate or love is important, we all deserve a reminder that sometimes you just need to shout out your favorite things. Here are a few of ours.

2 8 1 4

新しい日の誕生 (Birth of a New Day)

[Dream Catalogue; 2015]

HKE and Telepath spent the decade making some of the best ambient and dub techno to come out of the vaporwave scene, but 新しい日の誕生 was in a league of its own. For me — and because of that cover art, surely so for others too — it was the soundtrack to my first explorations of Tokyo, alone and lost and wondering about everything and nothing, caught in the July rain trying to find a place for myself in this crowded world. The jet lag had me pretty bad. At night, I would lay awake wondering when things in my life would start to make sense. By daybreak, I was exhausted, desperate to get out of my mind. As I listened to 新しい日の誕生 and wandered about, I never quite could. It was as if I watched the world from behind a screen. Still, however distantly, I could feel its warm heart. For years after I left, I craved the melancholy solitude of those long walks without purpose, form falling away, the world lost in a neon purple mist. The city, now more than ever, feels so big and unknowable. How many of these city dwellers were once caught in the rain, looking forward to a new day?

Ariana Grande

thank u, next

[Republic; 2019]

A theory of ghosts toward visitation as curative: that which haunts us wouldn’t if we didn’t tell its story. We author what lingers in the world by shaping the spaces that will house the haunt. This is not parasitism. This is memorializing in ectoplasm, the turning of memory outward. This is no mere metaphor either; in so much as we’re susceptible to being revisited by howling sensations (lust, grief, anger, melancholy), so too are we vulnerable to the shadows that inspire them. We twirl dissipated love ‘round spectral strands until a new want can be fortified with that which was, when loss becomes convex. We inoculate our futures in consideration with these apparitions, and we don’t decode ghosts: they unlock who we’ll be when we get to next. We carry so many phantoms in our bones and in our blood. We put them there. And sometimes we lean on the other fleshy bodies in our days to help us metabolize them and sometimes it’s the ghost alone who helps us heal. Don’t banish what came before, passed on, sought to reduce you, loved you in totality; cling to these things and render them — remember them — as shades that point to your now. And when you are able, sing and sigh and dance in fluorescence. Glean new ghosts. Live toward next.

Armand Hammer

ROME

[Backwoodz Studioz; 2017]

The American Dream Serpent choked on its tale. This was not a country in decline. This was the end. Did we laugh in the face of doom, or did we take the time to truly love ourselves, partners, and neighbors? ROME offered ample reason and opportunity for both. The album opened with a sonic embodiment of the cover art: a scorched-earth fiefdom overrun by a towering reaper rat. Elucid time traveled à la Black Quantum Futurism; billy woods traversed the diaspora, playing in the rubble. ROME was ultimately where the themes that these two clashing titans have unpacked through the decade — neocolonial strife, perpetual displacement, gallows-humor fatalism, inexorable autonomy — coalesced in a moment of entropic cartography. They talked that shit. The chickens came home to roost. The multiverse smiled back, and it looked like a pair of crowns. Armand Hammer’s era-defining effort yielded one of the best albums of all time, including the following bars of the decade: “Empire cycle, what a time to be sedated/ Narco haven, the lower the wage the bigger the gauge is/ With no regard to rising inflation/ Doubling down on shackling multiple generations in cages/ Free every goddamn body/ Free every goddamn body.”

Belong

Common Era

[Kranky; 2011]

“We are more than halfway done with another LP. It will be released on Kranky either later this year or very early next.” So said Belong’s Turk Dietrich to FACT when Common Era came out. Not sure what happened, but this third album sadly never came to pass. Dietrich resurfaced in 2016 in the experimental IDM duo Second Woman (with Telefon Tel Aviv’s Joshua Eustis) and this year with Duane Pitre as First Tone, but what became of Michael Jones is a mystery. Also in this interview, Dietrich had considered that fans of 2006’s October Language might be disappointed with this one. Could be they were, and perhaps that’s what stopped the project in its tracks. But, to some of us, Common Era became a resilient essential. And much like Helen’s The Original Faces, the album’s eventual one-off status has only added to its rarefied appeal. Without reinventing the wheel, this flawless collection of washed-out pop nonetheless felt innately essential. Though the distancing was intentional here, the pleasing effect was not unlike the happy (for us anyway) mixing accident of Akina Nakamori’s Fushigi. Common Era was an album of both numbing flatness and swaddling density, an opaque nightswim for the hyper-sensitive and gloriously aloof alike. We may never get another Belong record. However, especially having skipped the expectation merry-go-round of a larger discography, few go out this strong.

Blood Orange

Freetown Sound

[Domino; 2016]

The other day, I called my best friend who lives in New York to talk about my nervousness surrounding writing as a white author about an album centered on black grief. They tell me they don’t really want to listen to the album right now. “You don’t have to relive what I do.” They introduce me to Slave Play. We talk about Dev as behind-the-scenes in two of this decade’s best songs. I bring up my tendency to compare this record to nothing other than What’s Going On. After all, it’s a narrative of listening, a one-way dialogue with a weeping world. It’s “not even an album.” It’s an ode (they love living in New York). It’s an elegy (I hate that they live in New York). It’s a voicemail. It’s a sticky note left by the ashtray for when you wake up that says “I’ll be back soon.” But will you? The pain of Freetown Sound could not be bought or sold. The project was a death of etymology, a crying out not from the blows of the past, but from the infinite swarm of trauma from the present. Its strickenness sourced from simultaneous communal grieving. But it was also pop, it was love. It embraced and it gave thanks to the community that could just as well be two people as 42 million. Before we hang up, they tell me they love me, and I say “I love you too.” I realize that I miss them so much that my heart is breaking.

Broken Water

Whet

[Night People; 2010]

The Pacific Northwest — and the sound it bequeathed a tired nation nearly 20 years before — was a dormant force on mainstream and underground music this decade. The region wasn’t dead, mind you, but it had become a hotbed of tech startups and behemoths alike. The flannel that was once its battle flag was no longer flying but laying in gutters, tattered as a forgotten memento. Olympia’s Broken Water wandered those streets, found the once-fashionable tartan, and gave it new life. Whet was not emblematic of a discarded sound, but rather of a region that became as disposable to pop culture as the music and spirit siphoned from it in the preceding years. Yet, its muddled production and heavy crunch not only recalled the area’s subterranean pop past, but also the electricity of its forebears such as the Sonics, with its lilting jangle amidst the grungy production. Despite expanding their sonic palate until they quietly dissolved in 2017, the band’s production never abandoned the sound of Whet, a sound both of the area and of the band itself that went into slumber alongside Broken Water.

Burial

Rival Dealer

[Hyperdub; 2014]

Despite being contentiously received upon its release, Burial’s “anti-bullying” EP arguably set the tone for the most influential music of the decade, turning the former dub-stepper’s refined miserablist aesthetic inside out, embracing cut-and-paste editing, rapid emotional shifts, and schmaltz alongside techno, big beat, and house. Rival Dealer ended up as a sort of crux for the decade in electronic music, summing up its conflicts of affect/sincerity and loop/narrative in brilliantly knotted fashion. As “you are a star!” rang out over an ascendant sample, Burial crumpled past/future and irony/sincerity. Elegiac yet starry-eyed, this was the sound of temporalities collapsing into hope. For the first time, Burial moved past the melancholy of the hauntological to a sound in which those ghosts of lost futures finally ruptured and broke open the present through emotional heft and muscular verve. The cheese of his samples performed the same joyful reformatting of signs that vaporwave and PC Music did, but through different, more aching tools, through more overt time-crumpling. Knee-jerk transitions rammed us through stylistic and emotional shifts; sampled spoken words spoke clearly of a desire to exist; the body emerged out of ashes; its slapdash nature felt all too contemporary, the deeply-felt alongside the barely-there. Burial’s rupture was a yearning. In the end, a nearly comically earnest paean to being yourself left one of the biggest marks on a decade of electronic music’s furious integration of time and bodies. And why not? As freak bodies returned to the rave in ever-increasing numbers, Burial provided them with a future, a past, a hope, and a dream.

Chance the Rapper

Acid Rap

[Self-Released; 2013]

No longer encumbered by the Chicago public school system and its draconian suspension policy, the 20-year-old Chancelor Bennett finally ran free on the celebratory Acid Rap. Here we saw Chance hopped up on xans and lysergics, pummeling through dalliances of footwork, boom bap, and soul with the energy of a grade schooler and the stamina of a marathon runner. The drugs fueled him, of course, but so did the trappings of his childhood that lingered in his not-so-distant past. Yet the Rapper’s musings on Rugrats VHS tapes and D4L MP3s could only propel him so far. “Acid Rain” was the mixtape’s comedown, the moment Chance realized his heroes fell from grace long ago and that he’d outlived some of the role models who provided guidance through the violence and acrimony permeating his beloved Chicago. Still young enough to know where to seek respite, Bennett closed out his triumphant sophomore record with a loving voicemail from his father. Acid Rap captured a significant moment in Chance the Rapper’s life, one in which he had to reconcile the compulsion toward consequence-free adolescence and brace himself against rigors of adulthood. Every brat has to grow up some time; it can’t be all cocoa butter and grilled cheeses forever.

Dawn Richard

Blackheart

[Our Dawn; 2015]

“I thought I lost it all,” sang Dawn Richard in the opening seconds of Blackheart. And she almost did. Blackheart was a creative gamble of a record that the former girl group star struggled to even get made, but when it was finally released, it hit with the catharsis and ecstasy of winning a jackpot. The album overflowed with strokes of genius, from the tripping-over-itself breakbeat rush of “Calypso” to space R&B sprawl like “Adderall/Sold (Outerlude)” to the twin pop epics of “Warriors” and partial Danity Kane-reunion “Phoenix.” Richard nailed every moment with a commitment and confidence, only amplified by the label and financial setbacks she fought through. It was one of the most inspiring and genuinely transcendent moments in pop music, an artist reclaiming their story in the face of a skeptical industry and becoming the star they were destined to be.

Diddy - Dirty Money

Last Train To Paris

[Bad Boy; 2010]

Absent from the virtually non-existent critical discourse on Last Train to Paris was any mention of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. The two came out about a month apart and, in retrospect, have no business being considered independently of one another (oft-overlooked in discussion of the latter’s self-absorbed grandiosity is that it was the style of the time). They’re not so much comparable as they are equally beyond compare: the outros of “Your Love” and “Ass On The Floor” were not reminiscent of specific tracks from MBDTF but rather entirely impossible to imagine on any other album. Ostensibly, Paris’s narrative was more robust, but one could be forgiven for not realizing that the songs were in any way thematically connected. Instead, the album functioned as an alternative, show-not-tell approach to Kanye’s mildly over-appreciated point: fame’s not that tight. How, in 2010, could Diddy’s itch for recognition possibly have remained unscratched? No one asked, but Last Train To Paris answered.

(Justice for Dawn Richard, in this writer’s mind the essential artist of the decade, for turning her Dirty Money clean; justice for Shawty Redd, who was ahead of everybody).

Dragging An Ox Through Water

Panic Sentry

[Mississippi/Eggy; 2014]

With his lonesome, steady voice and idioelectric gizmos, Brian Mumford’s Dragging an Ox Through Water sculptured something of an eremite image. Alone only to tinker with chords and give expression to mercurial current, each of Panic Sentry’s songs felt like a rare visitation from the hermitage and a uniquely affecting document of simple, direct potency. These were delicate songs, as friable as the man and machines that made them. Squealing, swelling, burbling issuances from obstinate, jury-rigged electronics cradled and disrupted his low mumbled melancholia, his feral nature, his thirst for war. “I am turning into scum,” he crooned, as a violin grinded away behind him. Postures assumed with intelligent self-deprecation indulged in hopelessness and disintegrated under their own reflection. He was a wolf in disguise. He was a witch in the lowlands. He was ally to the rats and the weeds. Every element of these recordings converged toward this sense of being at the margins in a place pregnant, powerful, and wholly apart. There was beautiful, difficult life in the evil forest.

E+E

☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆

[Self-Released; 2013]

☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆ comprised some of the most delicate and refined works of Elysia Crampton. Back in the days of her E+E moniker, Crampton drew new boundaries for electronic music with her precise fusion of huayno, Afro-Bolivian saya, and cumbia. On ☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆, she laced vibrant rhythms and flagrant pulses of Latin America with foreboding ambient and choral music, which drifted and indented the impeccable tracklist that made this one of the most important releases of Crampton’s catalog. Even though ☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆ is near impossible to find — it was originally a SoundCloud playlist, with several of its tracks off Bound Adam — and indeed does not exist as an official release, it remains an impeccable piece of work and a testament to the creativity of one of this decade’s finest.

Future City Love Stories

Future City Love Stories

[BLCR Laboratories; 2017]

You and I have met before. Remember? We moved into an underground skyscraper, where Future City Love Stories rained down from the soul of the sprawl. They carried ambient lamentations and autobiographical elegies from the crowded interior, swept into the deepest and lowest gutters: graffiti-stained tunnels, gacha alleyways, arteries of black machine static. They throbbed in cosmopolitan aggregate: traffic vibrations, the heavy trickle of greasy rain, notes from an upscale hotel, advertising lingo in another language. Whose voices were they, again? I can faintly remember… They change in mood but not circumstances, almost like us. We used to talk different, feel different. Remember? But that light will never break again. Not down here.

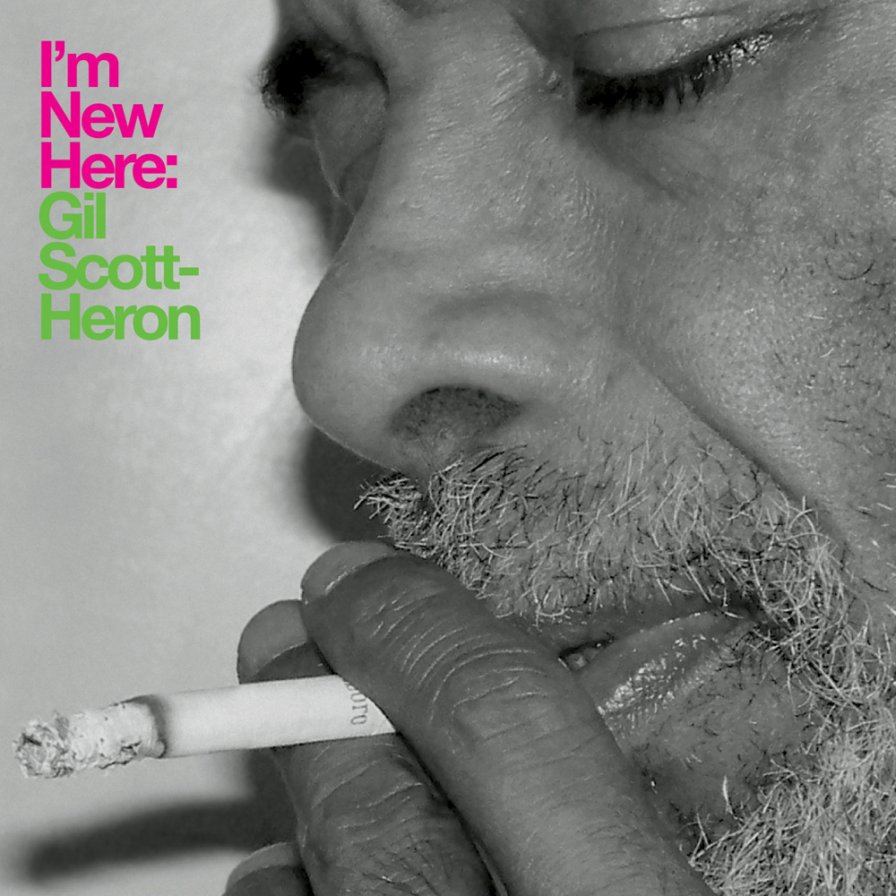

Gil Scott-Heron

I’m New Here

[XL; 2010]

After a legendary run of 13 albums in 13 years, from 1970-82, Gil Scott-Heron largely disappeared from public view. In the 2000s, he was in and out of prison on drug charges, in danger of letting his legacy slip away from him. To those in the know, Scott-Heron was the godfather of rap, but to many in the younger generation, he was remembered, if at all, solely for the 1970 track “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” By 2008, though, Scott-Heron was out on parole and planning his comeback. I’m New Here was a short album that borrowed its title track from Bill Callahan and featured just as many spoken-word pieces as proper tunes. Against all odds, it worked. The album sparked a Scott-Heron revival, helped along by Jamie xx’s remix album We’re New Here. Scott-Heron’s tired, smoky rasp was way up in the mix, his humor and his pain on full display, his sensibility hyper-modern, his musical chops sharp as ever. Scott-Heron died a little over a year after the album’s release, but he had achieved the nearly impossible act of crafting a comeback album that redefined his legacy. For some listeners, he was new here; for others, it was a pleasure to welcome him back.

Holly Herndon

Platform

[4AD/RVNG Intl.; 2015]

“It’s levels to this shit.” I can only assume that when Meek Mill said this, he was talking about Holly Herndon’s multifarious and prismatic “NSA breakup album,” Platform. There was a lot of lot-ness in it; there’s no pretending that it wasn’t dense, heady, and even a bit pretentious. Platform made IDM’s goofy acronym seem a little less ridiculous; if there were such a thing as “intelligent dance music,” this was it. What it wasn’t, however, was unaware of its aims and its affect, of its theoreticality and its materiality. Making distinctions between “club” and “academy” though is a tired and boring starting point for dissecting this kind of shit; Herndon’s reality is that she’s got one foot in both spaces, and Platform’s most visceral sonic tensions stemmed from this, in striking and bodacious ways. Hearing Herndon justify her project in her own voice was fascinating, but what was so special about Platform was that, despite its staggering profundity, it spoke for itself; like a Tolkien novel, its sheer awesomeness was only strengthened by its conceptual depth. There was still snippets of brilliance and power I’m finding in it, even as I dance to “Chorus” in my broken desk chair. So yeah, Meek, I agree: It’s levels to this shit, and Platform still succeeds on every one.

Ital Tek

Bodied

[Planet Mu; 2018]

A trend in the 2010s was an increasing tendency for electronic musicians to try their hand in scoring for film and video games. Ital Tek, having just written the soundtrack for video game Laser League, named his following album Bodied after a gaming term for death. Ital Tek’s dark dubstep roots continued to grow fainter as he explored the emotional depths of bass music, delving deeper into what he had established with the equally transcendent Hollowed in 2016. Relying less on thudding beats and leaning more toward melancholic, atmospheric excursions led to a record that was by far one of his most visual. Developing a language of skittering percussion and growling, arpeggiated bass lines kept the entire album injected with a dazzling, grandiose flavor that only grew more epic as it progressed.

Jim O’Rourke

Simple Songs

[Drag City; 2015]

Jim O’Rourke’s Simple Songs, popularly referred to as his third “singer-songwriter” album, was released almost 14 years after Insignificance. And it was just as brilliant: In a parallel universe, tracks like “End of the Road,” “Half Life Crisis,” and “Last Year” would be hit singles pored over and dissected by historians for their unique contributions to modern society and popular culture. But while Simple Songs was just as overwhelmingly creative and diabolically clever as its predecessor, it also found O’Rourke in a more subjective, winsome mood. He was still funny as hell — proving himself to be the king of one-liners and the greatest out-of-work comedian of the last three decades — but his lyrics here were more relatable and inflected with sadness. These simple songs were simply captivating. O’Rourke, working once again with high-caliber musicians and master masterer John Golden, delivered an album more than worth the nearly decade and a half it took to see the light of day. Here’s hoping he’s hard at work on number four.

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

なんだこれくしょん (Nanda Collection)

[Unborde; 2013]

I’ve read a lot of colorful, inflated stories about the Harajuku district, an epicenter in Japan for street fashion and youth culture. Then I visited, and while the streets did indeed boast wild outfits and concentrated pockets of fantasia, it felt tame compared to the hyperbolic descriptions of it. (Didn’t help that American Eagle was just down the street.) But while it’s easy to sell a simulacrum of Japanese culture through the frame of Western fetishism, it’s difficult to overstate the sensory overload and colorful aesthetics exploding from Nanda Collection. Even six years since its release, Nanda Collection — which translates, appropriately, to “What’s this collection?” — pushed further than many of today’s most experimental pop, finding itself drenched in highly-stylized productions that matched the outrageous exuberance and infantilized provocations of Harajuku Princess and fashion monster Kyary Pamyu Pamyu. Erupting with powerpuff melodies, sprightly syncopations, and a playful, almost cartoonish approach to genre, the album had the capacity to both overwhelm our senses and effectuate desire, every second of it brilliantly and obsessively embellished by mastermind producer Yasutaka Nakata. Nanda Collection was truly one of this decade’s great pop experiments, J-pop or otherwise, one that helped spark the internal conditions for pop’s own violent rupture, which we are still seeing play out today in all its grotesque, carnivalesque glory.

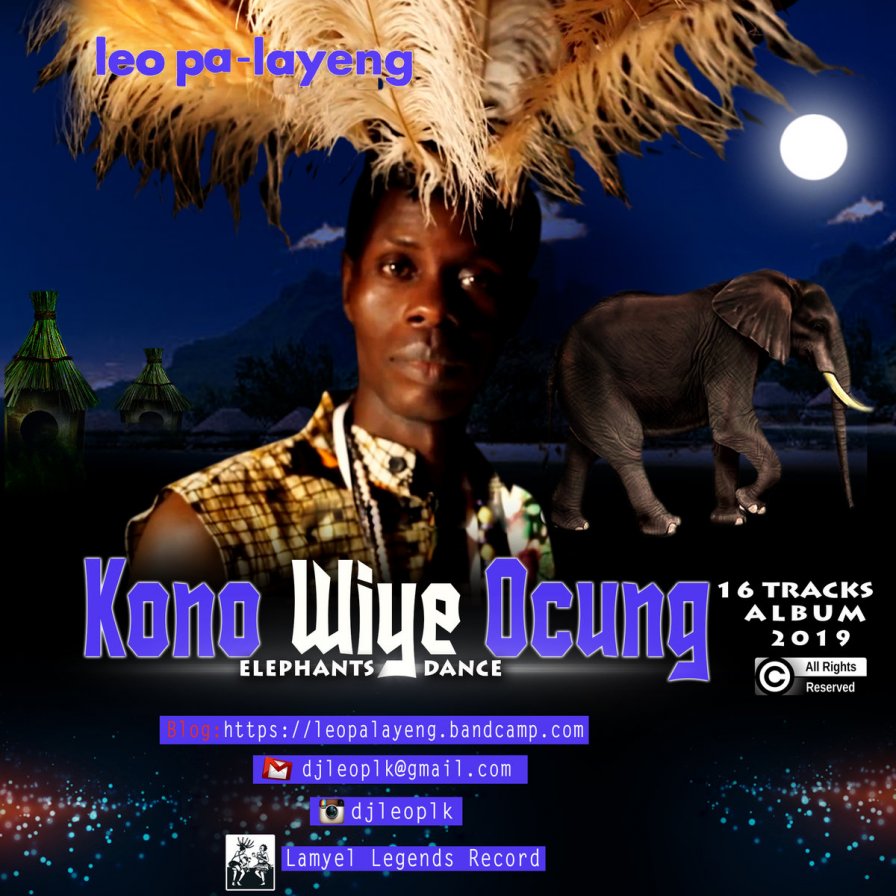

Leo PaLayeng

KONO WIYE OCUNG

[Lamyel Legends; 2019]

KONO WIYE OCUNG was unbridled excess: of tempo, of timbre, of sheer radiant joy. This was the electro Acholi kaboom, albeit one that seemed to completely outrun our critical apparatus altogether upon release (with regard to its relatively low profile in the nebulous world of Online). An altruistic narrative spirit pervaded here, as Leo PaLayeng Kenna weaved traditional folk musics, instruments, stories, and characters with electronic embellishments that provided a generous update on its highly localized source material. In fact, there was no need to compromise on the histories that coalesced here — the best testament to that fact came on “AWIDI LEGACY,” wherein Leo PaLayeng invited us to celebrate an Acholi princess whose dance “attracted many fragmented tribes,” an embodied “Super Cultural diversified, in the sunshine land of Africa.” That was precisely KONO WIYE OCUNG’s M.O., an album that pressed on with such a fundamental openness, grounded in its particularity, that it enjoined its listeners in irresistible communality and material release.

Light Asylum

Light Asylum

[Mexican Summer; 2012]

Before everyone started re-evaluating 1990s nu metal (which, all yuks/nostalgia aside, never got any more palatable than Faith No More), Shannon Funchess and Bruno Coviello were putting their heads together to breathe new life into the sounds of the previous decade, of which many of the less-heralded innovators have gradually reclaimed from its interminable, toothless wash of MOR security blanket nostalgia. Like the best darkwave acts of the 1980s, Light Asylum took the pleasing overtones of new wave and artfully blended it with unadulterated ferocity and anguish. Despite the gorgeous single “A Certain Person” having been slung on the end of this debut, song-to-song the listener was helplessly drawn in, making that 2010 highlight feel like an old equine friend once arrived at. The most confounding aspect of this group’s subsequent dissolution is how unstoppable Funchess proved herself at writing vocal hooks (perfectly complemented by her and Coviello’s muscular, richly accented instrumental arrangements). These songs embodied a tight, sing-along-inspiring quality that obliterated any reservations about lyrics (definitely on the hokey side at times). Her baritone vibrato was a thing of rare command and, for a moment, a distinctive voice in a genre that could still use one.

Kawabata Makoto’s Mainliner

Revelation Space

[Riot Season; 2013]

The unexpected reappearance of Kawabata Makoto’s Mainliner with Revelation Space marked a revival of some of the best things about the extraordinarily debased rock of their definitive earlier album, Mellow Out: production blown-out to the point where Makoto’s guitar — leads or riffs as raw as you could hope for — frequently disintegrated almost to white noise, from repetition to dissipation. Still, the vocals were one of the things that made Revelation Space far more than just a retread — Bo Ningen’s Kawabe Taigen (sometimes also to be found collaborating with TMT favorite Foodman) was an inspired replacement for the currently “inactive” Asahito Nanjo, similar and yet distinctive. But if this still sounds too much like a “reunion album,” worryingly close to nostalgia, well for my part Revelation Space was formed of a set of sounds that bypassed every supposedly higher faculty in me. It perfected that sound, distilled something uncanny and essential from it; whatever historical and physiological quirks led to our appreciation for foolish things like distortion and feedback, Revelation Space conjured a hidden necessity in them. There’s something to be said for creating new sounds in new combinations, but there is also something to be said for pushing the substrate to the point of dissolution, while the form stays just scarcely perceptible beneath the surface.

Michael Pisaro

the earth and the sky

[Erstwhile; 2016]

From Webern through Cage, Nono through Wandelweiser, the thread running through this century of composition — incidental but ideological, even spiritual — found its beginning and end in silences. No matter the slipperiness of the experience or even the form, silence is myriad but definite: you know it when you hear it. In many ways (especially the weirdly particular ones), my encounters with Michael Pisaro over this decade have adjusted my hearing and have attuned my sense. Because of his work, I now listen better. This is a gift for which I’m unspeakably grateful. This retrospective, the earth and the sky, which to me stands out among the others (least of all because of the great album art), is the perfect entryway into his art. Listen, now; it will only become more necessary.

Midnight Sister

Saturn Over Sunset

[Jagjaguwar; 2017]

Midnight Sister’s Saturn Over Sunset was something of a breath of fresh air for me. With a shock of pink and blue, the album vamped its way into the end of the decade, unwaveringly mature and self-assured for a debut from a duo, neither of whose backgrounds were in pop music. Although it was noted for its evocations of old Hollywood, it got there by way of the art pop of the 2000s and the glam rock of the 1970s. Rooted in the past without being derivative, it avoided pastiche in creating something at once alien, familiar, and altogether vital. Dramatic but understated, its indulgences and eccentricities felt not forced, but like the guileless product of creating something for the joy of making it. Delicate but chaotic, it recalled the sensibilities of Broadcast and Deerhoof without sounding anything like them. Haunting and mischievous, its charms were overt enough to seduce but with enough depth to continually surprise. The rare album that makes me laugh, it was a work of contradictions I’ll be revisiting for a long time.

Moonface

City Wrecker

[Jagjaguwar; 2014]

This one’s for the dragonslayer! For melodrama, romance, and devastation. When pressed, in my fantasies, where this sort of question gets asked, I told you that my Favorite Album of All-Time is either Nina Simone & Piano or Grouper’s Ruins. Or this. Ten years of music to pick from, and this embarrassing little companion EP picked me, all because, “A daughter of a dove keeps me.” Released on my hometown label soon after I’d moved to Chicago and long before I would move to Austin, City Wrecker remained the perfect score for transitions, which in my experience involve upheaval, wrecking self-doubt, and the ruins I left behind in myself, all this water. I’m grateful for it. For Gil and Paps, whose pianos captured my ear before I could write. For Swan Lake and Gumshoe’s pan of Beast Moans, the first Tiny Mix Tapes review I ever read. For Cokemachineglow, whose curtain call provided me a blueprint for music writing. For Sunset Rubdown, Wolf Parade, and Moonface. For Spencer Krug’s cigarette in 2006 and his long hair in 2016. This black-and-white piano sounded the spirituality I needed, the heartbreaking bravery it takes to split the difference between what I know deep down and what I pretend, between the things I do and the things I say, between you and me.

Motion Sickness of Time Travel

Ballades

[Hooker Vision; 2013-2014]

I’d always been someone in between. Someone who wouldn’t fit neatly into the demographic checkboxes people are fond of these days. Hell, been that way growing up. I didn’t live in the suburbs, but I didn’t live in the rural backroads that mark the western half of Rhode Island either. I lived in between. Many contemptuous people, their noses upturned, would call it the “edge of civilization.” But that’s been my life. It was never one thing or the other. In this rigid walled-up world of ours, that’s unforgivable. It made me “special,” a marking nobody should ever want though they crave it now. But what can I do? [Music reminds me of who I am.] The sounds that envelop me help me remember the places I’ve been, where I didn’t belong for one reason or another. Some might find this obstinate, but that’s simply because they fear the past. Of course, I’ve never indulged in nostalgia: Tragedies and rejection littered the timeline. Rather, I tried to understand my mistakes, understand the situation more, so I can do better. This can be the only way forward: Through the rural backroads, over the blank spaces of suburbia, past the battle lines of urban neighborhoods. [I will need to stand up for myself.] But that’s something I’ve always done, no matter the cost.

Niño de Elche

Antología del Cante Flamenco Heterodoxo

[Sony; 2018]

We were in the living room of my apartment in Cartagena trying to put together a desk chair, me & my cousin. I’d bought a mini boombox for the living room to play from my CDs, but couldn’t think of anything in my collection that my cousin in his early fifties could get into. So I connected my phone via Bluetooth… OK, “Recently Added”… hmm, I’m not sure if you’re gonna dig this — it’s, like, experimental flamenco. Just give it a shot. A few songs in: Wait, let’s skip this one — it’s a nine-minute organ drone piece. “No, no, it’s nice — leave it.” OK, not the next one though — it’s a collage of manipulated vocal samples. “Wait — let me see.” By the time we reached “Recitando de Eugenio Noel” we’d skipped nothing of Niño de Elche’s nearly two-hour, monumental double-record; some the most fascinating — no, fucking genius — music the decade produced. With the voice of Francisco Contreras Molina — which I refuse to describe as anything but imponente — rising into a crescendo over a polyrhythm of cajones, castanetas y palmas, the desk chair faded into a vague haze: Quiet, music is happening. When we woke up, we forgot where we’d left the screwdriver.

Oren Ambarchi

Audience of One

[Touch; 2012]

Maybe it’s too much to say that Oren Ambarchi’s Audience of One lays itself bare from its beginning rather than its notable, commanding centerpiece, “Knots”? But so much is made of epics, especially as this entire album flows seamlessly throughout. This album is full of retrospective consideration, even nostalgia, that you happen upon each track as though it is, itself, a phenomenology of its own inception, a gesture toward near-Proustian storytelling. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe Audience of One is a brute fact of growth; indeed, this album is like a hinge for Ambarchi, the work opening onto yet another phase of his art. It ends with a glorious, almost corny celebration of the matter of which it’s made. And yet: I should heed James’s words: “music. is. never. abstract.” It’s we who are abstract. I’m making too much of this, reading too much into all of it. Grasping. But sitting here, I remember my first encounter with this incredible album: I was out on a walk, and this music shimmered and shook the world. Seven years later, I’m still shaken and remembering. There is a desire to read too much into works like these, but they’re already smarter than us. They know who their audience is.

Pepe Deluxé

Queen of the Wave

[Asthmatic Kitty; 2012]

I started writing about music sometime after the millennium, but it wasn’t until Mr P took me on at Tiny Mix Tapes in 2004 that my Almost Famous dream became real. It’s been an honor to write for him over the years and a profound pleasure to see what this publication has become, often because and occasionally in spite of my own contributions. That said, though I am grateful for having worked with one of the most creative, humorous, and supportive editors I’ve ever known, I am willing to stake my entire career as a critic on Queen of the Wave by Pepe Deluxé.

No other album that I’m aware of has been as imaginatively ambitious yet so modestly funded. It took this independent Finnish collaborative art project, helmed by mad producer James Spectrum and ace tunesmith Paul Malmström, some six years to complete this three-part psychedelic surf rock Cirque du Soleil-in-a-sauna apocalyptic acid trip baroque pop opera, which finally saw the light of day in 2012. It featured nearly every organ ever created (including the world’s largest instrument, the Great Stalacpipe Organ), recorded with a gear list of incomparable eclecticism (from a cosmonaut mic and a wire recorder to a pneumatic rhythm machine and a Tesla coil synthesizer), while the whimsical libretto was based on an automatically channeled book about Atlantis. It”s insane.

The group subsequently sold a one-off original EP to legendary pornstar Ron Jeremy in order to fund a follow-up full-length, which they are still working on at the time of this writing, many years later. They may burn that record in the woods in tribute to Jean Sibelius for all we know. What is certain is that Queen of the Wave is not only one of the most incredible albums of this decade, but of all-time and in any conceivable dimension. I felt that way the first time I heard it, and, if anything, that feeling has only become stronger over time. If this is the hill that I must die on, so be it.

Perfume Genius

Learning

[Matador; 2010]

“No one will answer your prayers/ Until you take off that dress.” The album’s opening couplet captured in a knot of little words the long history of subjugation of gender otherness and otherness in general, chillingly set to a jaunty piano four-hands arrangement, victim and perpetrator together. “But you will learn to mind me/ And you will learn to survive me.” Mike Hadreas drew intimate, second-person sketches of suffering, his heart overflowing with compassion, cutting in snippets of narrative — a girl hiding the mouthwash from her mother, a teacher making a tape of Joy Division for the student whose “body kept him up at night.” The default setting was Hadreas alone at his Caretaker-timbered piano, but elsewhere there were majestic, billowing organs and lovely codas of distorted filigree, all around a core of darkly banging melodies. “Lookout Lookout” had a moment of black humor — “you carved out a name for yourself” referenced 11-year old murderer Mary Bell, who carved her initial into her victim’s abdomen — but that was an outlier in an album that did its best to stretch its slender arms around haunted cathedrals of pain.

Pharmakon

Abandon

[Sacred Bones; 2013]

Few artists spoke with the raw intensity of Margaret Chardiet in this decade, but it was her first statement that stands as the starkest and most brutal of her work so far. Abandon’s shattering vocals over a minimal, percussive noise formed the foundation for Chardiet’s imagistic lyrics, explorations of the vegetal, bestial body cast in the purifying violence of fire and hatred. From the initial scream that obliterated into a single tone, Chardiet manipulated her voice to merge with the violent industrial backdrop, obscuring the edges of embodiment and realizing the lyrics’ craving for separation from the body. On “Crawling on Bruised Knees,” a sputtering tremolo cut up Chardiet’s voice as she intoned that she’s “bound to a vision [she has] not yet created.” It’s difficult to imagine a vision surpassing Abandon, but we look forward to Pharmakon’s further realization in the 2020s.

Powerdove

Arrest

[Murailles; 2014]

Late one night in 2015, a few dozen music devotees communed in a small college classroom in Santa Clarita. The only light in the room was that of Annie Lewandowski’s headlamp and the twinning LED bulb rigged inside a plastic cone — a DIY sound-directing apparatus that the artist had fashioned to mute, expose, and direct the sounds coming from her synth, the only sound in the room besides her voice. This tool, when pushed against her stomach or leg, was simple, like holding a phone speaker to the mouth and manipulating shape and size to change the resonance of the sound moving through (something we learned when we were young, along with our early experiment with feedback: putting two phones on call, switching both to speaker, and holding them together, forcing them to bed one another in reckless din). In that classroom, the method was simple, but we all watched as she exerted technique, manifesting emotion and tenderness while drawing our attention to the strange miracle of sound.

Later, Powerdove’s Arrest became the sounds found under covers: touching, infatuated, and electric. Buzzes and chirps, drums that squelched, clarity in dissonance, desire prolonged. Here, whirring, harsh and frail, filled the corners that the songs couldn’t reach. These songs, often only a few chords, didn’t reach far; they didn’t need to. Each one was like an object, material and cooking, available, steady, allowing projection. Love letters, cosmic pleas, and personal myths relying upon oral tradition. Arrest was singular and private, one of a kind, a record only for the self and only for others. It was an incredibly important reminder that, “After dark, we couldn’t find the other/ We couldn’t see each other/ We couldn’t see.”

Prurient

Frozen Niagara Falls

[Profound Lore; 2015]

The 2010s were a decade of dissolution, of fits of anger and sporadic explosion, but ultimately it lacked the tidal energy to force the apocalyptic crisis the early parts of the decade seemed to promise. But few releases from this decade adequately situated the bathetic impotence of the mass of civilization quite like Prurient’s Frozen Niagara Falls, a towering monolith of ice and shattering violence. “The guillotine is sleeping,” Dominick Fernow spat into a haze of chaotic noise, launching an hour and a half of sublimated fear, bracing static, and powerful critique of the hedonism, inauthenticity, and depersonalization of the current moment. It was Fernow’s most profound statement of the decade, and few others matched its intensity or resolve in attacking the acidic nihilism that fed the darkness of the final stages of the 2010s. We’re left with a lasting image of a penniless, powerless messiah warming hands over a burning garbage can, denied an apocalypse, drunk, broken, trying to remember the prayers.

Pure X

Pleasure

[Acéphale; 2011]

Finally, when you press your palms deep into your eyes and you’re half dreaming, slouched with no wings, half alive, your shoulders wrapped forward with blades pointed toward walls, time seems to die like fruit flies in summer kitchens with windows open and beer bottles lined like school kids at bus stops. Life can be filled with such longing, such unfulfillable longing that certain moments become callbacks in your genes to be shared with yourself for no other purpose than inflicting pangs of circulation. Memories are always re-remembered, puffed and dragged into new/old dust. Parties thrown with yourself for the sake of new memories, being that they are old memories, new/old to you, forever. The moon sunk like butter in a pan. That shifting lover back from their trip but on the opposite edge of the bed now asleep, exhausted, alone, and crumpled while you wait for some form of touch and mouth and glass to see back with. Thoughts paced like rapids while you breathe at the ceiling: them at the bedframe. Direction swelled. A junction of impermanence, projection, misunderstanding, and profound love — like sweet, tragic music. You, still, masked with lipped innards. Replete with memory.

Roc Marciano

Reloaded

[Decon; 2012]

When I listen to Reloaded, I hear self-determination, dream realization, a DIY ethos that has nothing to do with starving and everything to do with taste. Marciano’s gift for imagery is such that it’s easy to get caught up on the material, to get snagged on the “Thread Count” and miss the line in that song that goes “my inner layers is the Himalayas.” When I listen to Reloaded, I hear “you make art because you have to, because you don’t have any choice, it’s not about talent, it’s about no choice but to do it,” and then I think about what goes into penning lines like “Crime ambassador/ My capturers channel my spirit through a shrine in Africa/ I fly past like a time traveler.” I hear Dave Jordan sample biting “76.” I think about the proximity of Garden City’s country clubs to Terrace Avenue and of Terrace Avenue to Nassau County District Court. With this in mind, it’s easy to place Reloaded in a tradition of Long Island Rap Records that includes The 18th Letter, Black Bastards, Symptomatic of a Greater Ill, and Stakes Is High — not necessarily the island’s best, but quite possibly our best representations. I listen to Reloaded and I feel pain, pride, and potential in a way that I can’t explain, except to say I feel home.

RP Boo

Legacy

[Planet Mu; 2013]

It’s probably good that this side of footwork never caught on; pity though, and humorous that RP Boo’s decade-spanning collection of trax, aptly titled Legacy, would eventually be usurped by a smoother sound of Chicago footwork. It makes sense, though, and pop music is better for Rashad’s pervasive influence, but there’s nothing like that steady percolating beat and throbbing bass on “Speakers R-4 (Sounds),” or those stuttering drumline toms on “Sentimental,” or that truly transmigrational cymbal crash on “Area 72.” For what was basically a compilation, Legacy flowed like a bedside pageturner, imbued with as much action as mystery. Legacy was my first footwork album; I didn’t like it at first, but I furiously kept listening, like a dorky white anthropologist, secretly searching for a higher truth in a foreign culture. When it finally clicked, after I bought the damn CD, I knew it was done for. “There’s no way this is carrying footwork through this decade, not with Jlin and Diamond and Traxman around.” It has since become like a secret recipe you later find out is just salt, but since I’m feeling generous this holiday season, I’m sharing this with you: Go buy a copy of Legacy on compact disc and put it in your car and crank it. Your Red Bull-drinking, FlyLo-bumping passengers won’t know what hit them, but you will.

Salem

King Night

[IAMSOUND; 2010]

Was King Night a laughingstock of try-hard cool, or was it really that cool? In the end, it was the latter, but maybe only because of the former. Salem’s bargain bin desolation and grandiosely skeletal angst was the peak of a certain mood. (It was also the peak of “witch house,” the microgenre that spawned the million micro genres that together would define the middle of the decade.) They tore everything from the concept of “cool” until there was nothing there but some lonely trap drums, some overpowered synths, and scraps of offensive vocalizing, boiled down to a handful of drugs and a few signifiers of malaise and misery. That, of course, was the peak of a certain “cool.” In crafting a sound that was pure affect and absolutely nothing more, they carved a way through empty posturing and into a new world where posture was more than enough, an art in itself. They hadn’t found a “use” to that art yet, and wouldn’t, but that was King Night’s particular power: the feeling of helpless, devastated cool with no outlet. Upsetting, seductive, overwhelming, achingly empty, and utterly pointless, it did exactly what it intended to and nothing more, and it was remarkable for it. It felt like shit, it felt cool, as purely as possible, and that, certainly, was a mood for the decade.

sIngs

Hells

[Self-Released; 2010]

The Lord, he exists — just not in Texas. You can’t sleep outside in the summer because of the heat, and the cicadas are so loud there’s nothing to do but listen. I’m ungrateful. There is exhaust from the semis and the hum of ribbons of highway in various stages of torsion and elongation. Serrano’s out of town again. No, it’s not a dry heat in Houston, and the humidity feels like fetid cellophane in the windpipe. But at least it keeps the St. Augustine carpetlike until rapacious July stains it ochre. You might cherish the brief walk from home to your 2002 Jetta that you totaled on the day of your high school graduation, because it is the only time you will taste the petrichor before the air conditioning or the fucking mosquitoes brutalize its faint suggestion. No, there won’t be anyone outside, either, except the men in scrubs pushing meth outside Shepherd Plaza. And so you did what there was to do in the muggy lurch, and you drowned it out to Brett Taylor screaming his guts out and Pam Cantú and Colin Hedrick harmonizing and Chris Wise slapping the fuzzy bass and Jason Willis shredding and Justin Terrell keeping time. You were just the kid then, unendearingly reserved and guileless and feckless, stagnant like the people who own it. Well, it’s bad news from Houston: half my friends are dying. No, there is more to hear than the cicadas.

Sleigh Bells

Treats

[Mom+Pop/NEET; 2010]

Revisiting contemporary reviews of Treats reads, now, like a crash course on internet Crit. 101, with the distant hyperbole and de rigueur “X band meets Y artist” calculus. That’s not to say the reception was off or disingenuous — who the hell am I to say so? — but more that it was a maybe forced product of its cultural context: namely, the collapse of the late-2000s’s “blog-o-sphere” ecosystem. But, like, can you really blame anyone for maybe feeling like they had to get it? The music itself offered no easy metric by which you could weigh its influences, and the record’s noisiness (and sheer catchiness) obfuscated any cheap augury of meaning. Treats was hardly without precedent, but, still, nobody really knew what to call it, so they, to varying degrees, made shit up. That, to my ears, is partly what earns Treats a permanent place on the shelf. It’s a testament to the absurdity of the critic’s position in the culture market, reminding me of how ridiculous I was then and telling me how ridiculous I am now. A record that contains the will to surprise and confuse, especially in debut format, is something to cherish. And so, for me, the songs on Treats were, and always will be, exactly what the title suggests.

Sun Araw

Belomancie

[Sun Ark/Drag City; 2014]

The word “psychedelic” gets tossed around a lot to describe sounds that, ultimately, are fairly commonplace and predictable. Throw a phaser on it, heavy on the delay, sick guitar solo, “their Coachella set was amazing, bro.” But “psychedelic music as an active principle,” as Sun Araw would have it, is a much deeper concept than just tie-dye and shrooms. On Belomancie, the California lo-fi jammer stripped away the dense reverb that had previously shrouded his neo-tropical dub improvisations, allowing the silent space between each individual sound to stretch out into infinity. Abandoning his circular 4/4 loops, Belomancie’s constantly tumbling rhythms contracted and expanded at will, forcing us into a liminal zone where the only way to get ahold of our footing was to accept the lack of any floor at all. Listening to it was like staring at a plain white wall until the individual atoms between each stroke of paint started to fall into a strange half-step of their own. While Sun Araw’s earlier, more traditionally trippy releases like On Patrol and Ancient Romans were certainly potent, Belomancie was the album where he fully proved himself to be a master of shifting our perspective, using the barest of elements to rearrange the world around us into something totally new and unrecognizable. In other words: Belomancie was truly psychedelic.

The Austerity Program

Backsliders and Apostates Will Burn

[Hydra Head; 2010]

This fucking life, it’s a misery. A thing to be endured. You can face it with the stoic resignation of the grieving fisherman of “Song 25” or rage against it like Buzz the Bunny, locked in an endless cartoon hell. You can even crawl the earth in an evangelical fervor like the debased prophet of “Song 26” in the hope of finding some way out. But in the end, it’s all the same. You end up torn apart, “something forgotten in the ocean.” With their breakthrough EP, The Austerity Program gave us four perfect songs: soaring, crushing, snarling mini-masterpieces that spit in the face of this cold, indifferent universe. It was a record to be listened to loud and often, a brutal, majestic reminder of all the joy and horror of existing.

The Babies

Our House On the Hill

[Woodsist; 2012]

Oh Lord, have mercy on my soul, as it crumbles into the wind and stains the whole sky a shade of barbecue gone bad. Have mercy on my demon ass, jittering until I bruise, like a shattered animal with a shit heart. I know I said that every day makes me want to howl, but I learned to throw my face toward heaven and cackle while wandering into the void. Remember when I screamed that I would fling my corpse off this fucking mountain. What I meant was that I craved the sun bleeding onto my face and that I would jump into my car and drift toward the desert as soon as I chopped my hair like I have always been threatening. Promise me three things before you scuttle off the edge, promise that you will do my hair like you do it, promise that you will shake your hips, and promise that you will pour one out for the goddamn Babies.

The Brave Little Abacus

Just Got Back From the Discomfort—We’re Alright

[Self-Released; 2010]

You know that feeling when your heart is this close to breaking and you’re about to explode from cranial pressure and your eyes well up but you can’t find the words so your face strains and puffs out like a sea urchin and you really really want to explore different modes of being outside a human body but there’s no accounting for corporeality so you just have to deal with it because hey so is everyone else might as well connect through dread? You know that feeling, right? Just Got Back From the Discomfort—We’re Alright is that feeling: straight, undistilled, without restraint.

The Lonely Island

Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping

[Republic; 2016]

Shame on all of us for making this film a box office bomb. Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping is the best music documentary since This is Spinal Tap and perhaps the premier pure comedy of the 2010s. In terms of laughs per minute, it’s off the charts. “Wait a minute,” you, a heathen who has never seen this movie, ask impatiently, “isn’t this a list about music releases?” Guess what, hotshot? The soundtrack for Popstar was legit, positively ripe with hilarious parodies of pop music clichés that were also catchy as all get out. “I’m So Humble” beat Kendrick to the punch by a year, and no one ever talks about it. “Incredible Thoughts” dared to ask deep questions, like “What if a garbage man was actually smart?” And here was a stone cold fact: the hardest I laughed this entire decade was when I heard Andy Samberg as Connor4Real sing, “Knew she was a freak when she started talking/ She said, ‘Fuck me like we fucked Bin Laden’” for the first time. “Finest Girl,” a perfect song. Truly — and unlike the Mona Lisa — Popstar was far from an overrated piece of shit.

Tim Presley

The Wink

[Drag City; 2016]

The Wink was a breakup album for frantic romantics — bitterness and tears were mixed with hot colors and flung at the canvas or cut up into Syd Barrett word collages in a pacy state of regret, arousal and disbelief, “in an ostrich elevator and a book with dog-ears.” Producer Cate Le Bon stripped Tim Presley’s White Fence down to the gnarled wood and helped reassemble it into spiky abstract sculptures dusted with real rock flavor. Presley’s citrusy guitar scraped against old-time dance hall piano arpeggios, as his ecstatic recall of how “love was in his eyes” disintegrated into a sigh of “I know what you are…” The album’s showstopper was the gorgeous, purple-bruise ballad “Morris,” where Presley finally sat down with a cocktail or several and cut loose on his qualifier. “You could be excellent… if you don’t know,” he crooned, before narrowing his eyes: “Make the most of it / When you tell me that I’m ugly / Don’t ever put me on the moon again.”

TREE

Sunday School

[Gutter City Ent.; 2012]

In fall 2012, I penned my first feature for Tiny Mix Tapes, a would-be year-end essay Mr P rejected so kindly that I thought he’d accepted it. He published and paid me for it anyway; that’s how nice P is. On Sunday School — one of three subjects of that essay — TREE presented an ideation for hip-hop so unique, prescient, and polarizing that the genre’s biggest stars spent the rest of the decade struggling to reiterate it. That’s how nice TREE is. Yet, for all its genius — mining nuggets of golden-age gospel from pre-trap gang culture, syncopating beats and rhymes in ways rarely heard hitherto or since, taking rap music in an organically fruitful direction, etc. — Sunday School’s appeal was never academic. I got into it because I could play it over and over and over while heading to the beach, lying in the sand, and coming home. Technically, it’s not even a summer mixtape, having dropped in March, but I still find myself returning to it around that time of year, every year. With each one that passes by, I catch things I’d missed on previous listens, while radio rap creeps closer and closer to approximating its sound. If part of “aging well” is making more sense in light of what’s come to pass, Sunday School might have done the impossible in somehow actually getting younger. It’s miraculous. It’s… TREE!

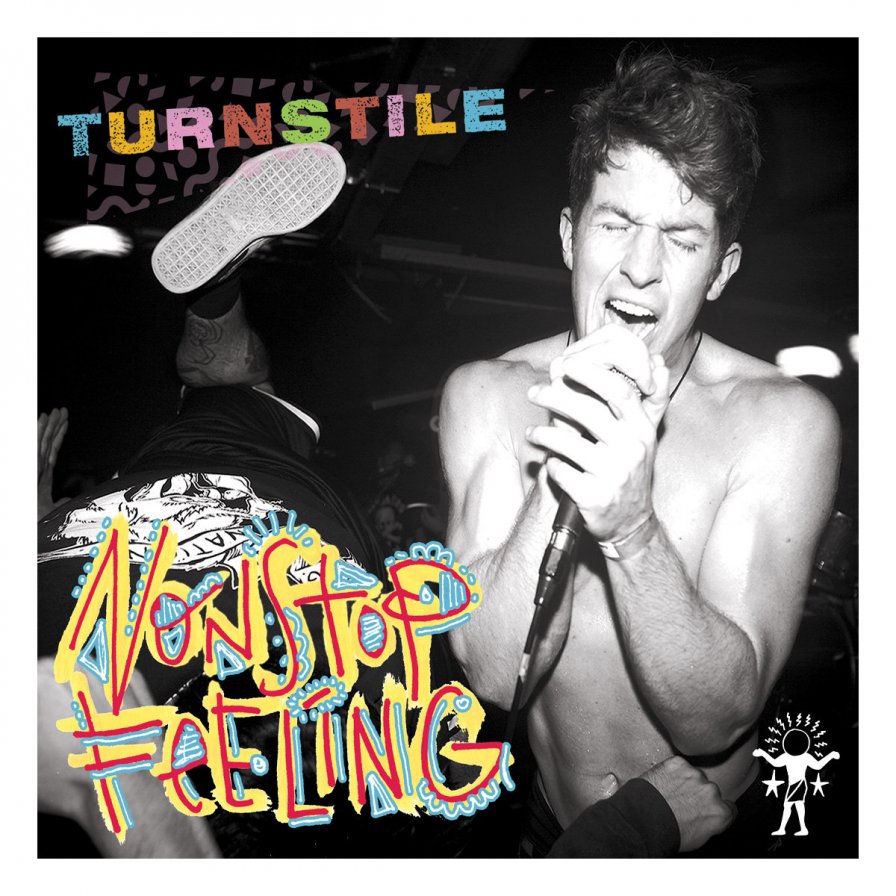

Turnstile

Nonstop Feeling

[Reaper; 2015]

A debut album can be a tantalizing promise and its simultaneous fulfillment. That’s doubly true in a volatile genre like hardcore, where bands frequently make one record and pop like balloons. Turnstile didn’t do this. They went on to sew their jumble of ideas into a more coherent sound instead, but their first album remains captivating for its ramshackle hotrodding of a bunch of shit together — they reminded you Rage Against the Machine was a kind of punk band; they put simple, pretty backup vocals behind Brendan Yates’s yelling throughout; they put a pit shot on the cover but topped it with multi-color scribble. The beauty of Nonstop Feeling was its lack of integration, its splatter of genre signifiers. I won’t say Turnstile started this decade’s trend of hardcore bands reclaiming parts of the 90s’s most maligned jock-rock subgenres, but they will be looked upon as emblems for it. The closeness to rap-rock made them a conversation piece, but moments of contradictory softness made the album three-dimensional: The surging power-pop of “Blue By You,” the contemplative, almost-surfy “Love Lasso.”

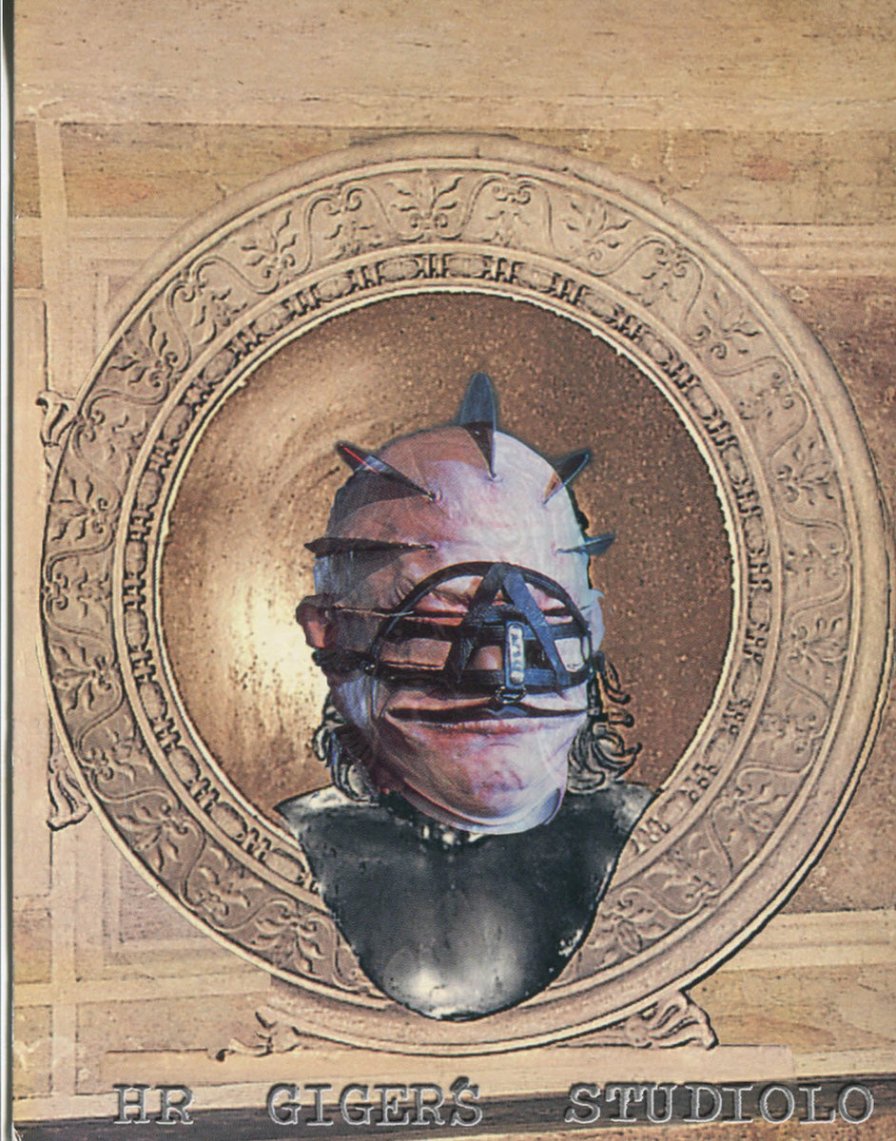

TYPHONIAN HIGHLIFE

H.R. GIGER’S STUDIOLO

[PACIFIC CITY SOUND VISIONS; 2014]

Sometimes there is no reason to describe such deep sensations, because the reflection will never do justice to the feelings. But the feelings put positivity and pressure on a need to gesture and to explore and to revel, because the magic within the sounds create too much connection. Heavy-set tubes from one brain plug into the brains of others, connecting them with joy and puzzlement and distillation, showing you a new way and keeping you completely informed. Never before has this experience been so real, because it props you up and stands you on a cliff edge overlooking your own body; you can take that journey because you have been given permission.

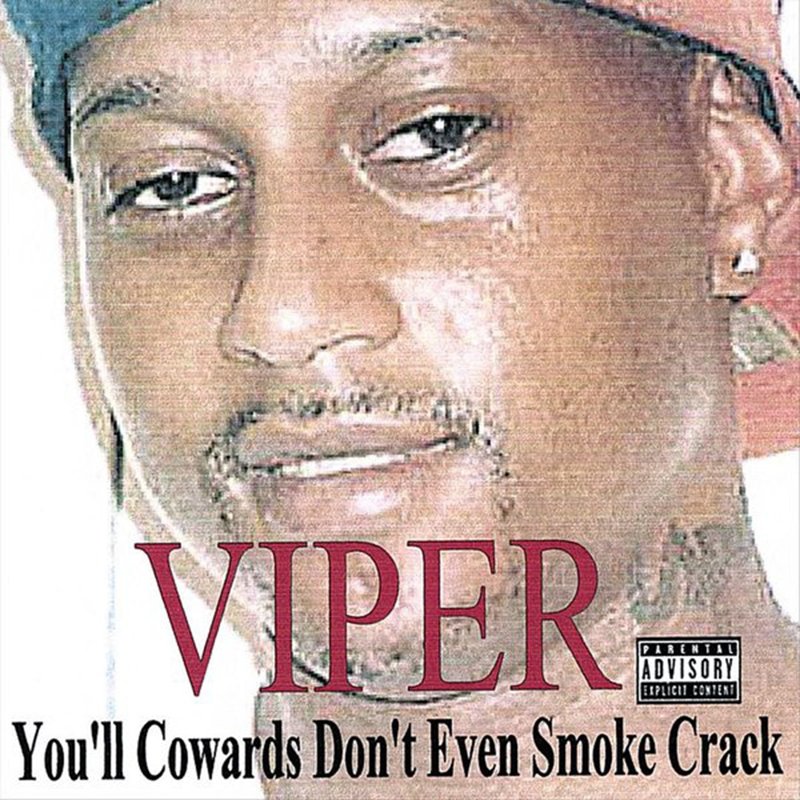

Viper

You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack

[Rhyme Time; 2008]

Two icons to frame this decade’s rap hustle: Viper and Kanye. Superficial distinctions aside, their careers followed mirroring paths. From man to myth to meme, from pop culture figure beyond good & evil to derided reprobate to, ultimately, an inscrutable creative force whose divisiveness couldn’t negate their cultural cache.

To be sure, while in the 2010s Kanye was in his second decade as a music industry luminary, Viper emerged from the entrails of the internet as much as a curio as an artistic visionary. Whereas avoiding every detail in Kanye’s life was often impossible, most people probably first encountered Viper as a viral sensation. In late 2013, “You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack” started to pop up in YouTube feeds, boards, and social media. From the title onward, the track had the discomforting rawness of outsider art, though it was not exactly that. It was old but not the latest Japanese synth-pop rarity spat-out by an algorithm. It was meme-worthy, but also the work of a serious artist. It was not too far from what Yung Lean, $uicideboy$, BONES, or many other SoundCloud rappers were releasing then; hence, half a decade ahead of its time. It was just tacky and unselfconscious enough to generate interest. It sounded good, and there was a lot more where it came from. And considering the hundreds of albums Viper has released since, that’s quite an understatement.

Then, what let You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack, a five-year-old record, capture the zeitgeist? Vaporwave, hypnagogic pop, the impish humor of Hype Williams, Lil B, and the meme rap scene provided the context for a weirdo who milked the presets of his cheap gear like a master, married chill beats with a mumbled flow, and boasted about the most ludicrous stuff while doped out of his mind to be right at the peak of the wave, even if for just an instant. With bangers like “Parlayin’,” “Merciless,” and the title track, Viper can claim to have made a dent in (online) pop culture in the 2010s. Influential? Transcendent? Who’s to say. As the decade nears its end, Kanye and Viper continue to be reliable sources of outrage and fascination. Perhaps their careers finally diverged on a hospital bed, where Kanye landed after a prolonged mental breakdown and Viper because of the pneumonia he developed from trying to shrink his torso using a harness. Upon recovering, Kanye remerged a Christian. Viper, to further complicate his already problematic relationship with fans, emerged to crowdsource content and try to force himself into meme-relevancy by claiming responsibility for 9/11 and Epstein’s demise. Such is the burden of genius.

Waak Waak Djungi

Waak Waak ga Min Min

[Efficient Space; 2018]

A pall of smog falls across the window of the air-conditioned office building from which I write, obscuring buildings no more than a few meters away. Despite the chilly air inside, I can still smell the smoke. In Australia, cities are choking while the country burns. In my country, our rainforest is going up in flames and our precious water is siphoned off by the megalitre to rapacious corporations. As an Aboriginal man, I’ve wondered whether we might respectfully borrow from Afrofuturist imaginings to understand what is happening — to seek ways to represent the intermingling of nature and technology under colonialism, and to sing of despair, but also of hope, of unfolding possibilities and the ways we can reclaim our stolen land both in art and in actuality.

In doing so, Waak Waak ga Min Min has been a touchstone — imagine, fingers brushing the smooth warm surface of a pebble pregnant like an egg with history and the promise of renewal, even if only in an (eternal) moment. Waak Waak Djungi are songmen from Yolngu country, far from my home, but their rough-edged, spiraling chants, interspersed with electronics and field recordings, speak to me deeply. But, for me at least, this is a “personal” engagement, where nonetheless, as a listener, one does not take in to the self, cultural appropriation-style. Instead, the self realizes its own littleness in its connection with landscape, history, and futurity, both recognizing otherness and how it refracts through one’s own circumstance, able to relax completely in the knowledge of being held without having to let go of either the fear of annihilation or the seed of resistance.

WU LYF

Go Tell Fire to the Mountain

[LYF; 2011]

WU LYF was a difficult band to talk about. Pronouncing their name out loud sounded like “Woo! Life!” which didn’t hold quite the same weight as World Unite Lucifer Youth Foundation. And their sound was equally difficult to elucidate — Ellery Roberts’s distinct lead mumbles were like a drunken Tom Waits slurring his words and trading swigs with an over-smoked Samuel Herring. Their guitar and drums crashed and hummed like an Explosions in the Sky track operating within traditional song structures. The band self-labeled their sound as “heavy pop,” which was a buzzy genre tag, but it didn’t actually mean anything. The fairest description might be that they played a sort of gospel music for a post-apocalyptic world, equal parts hope and cynicism. Besides a farewell song and a few remixes, Go Tell Fire to the Mountain was the entirety of the band’s output. Their sincerity and authenticity were eventually questioned, but that didn’t matter to me. My connection was real enough that I tattooed the WU LYF cross down my arm to memorialize a time of emotional upheaval in my life. Of course, WU LYF was also an acronym for World Unite Love You Forever, so maybe it was a celebration after all. Woo life, forever.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series