We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

05. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

05. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Dir. Apitchatpong Weerasethakul

[Strand Releasing]

Leaving his traditionally bifurcated structures behind, Apitchatpong Weerasethakul plunged even further into the realm of tropical surrealism, tapping into parallel realities and past lives with a delicate restraint that was all his own. There may have been a talking catfish and laser-eyed monkey ghosts, but these were fantastical only in theory. Onscreen, the abstractions were merely an extension of the mundane reality of Uncle Boonmee slowly fading from existence. The tropical setting, a mainstay for Weerasethakul’s films, once again provided a perfect locale for the director’s melding of animism and the mystical, the material and the spiritual, and the ordinary with the otherworldly. Boonmee operated on its own internal logic, modestly inviting the viewer to enter its world on its own terms, never offering any guidance through traditional narrative structure or action. Instead, Weerasethakul blurred the line between past and present, living and dead, and man and nature to achieve a remarkable spirituality that retained its quixotic, enigmatic form as it dealt, quite touchingly, with memory, death, and lost love.

• Strand: http://www.strandreleasing.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2dq3

04. Melancholia

04. Melancholia

Dir. Lars von Trier

[Magnolia]

How can one convey devastation? You can’t cry enough. You can’t scream enough. And you suddenly remember how comfortable boredom was. With Melancholia, we desperately shored up our aphorisms and metaphors like armchair embraces from phantom limbs. We went and paid to feel ‘more-than’ for a couple hours, basked in the vulgar rendering and sour aftertaste of countless bubbling milky melodramas. And then, all of a sudden, it was no sinking feeling, but a pure red-eyed state of fixed attention on the end of the fucking line. Exhilaration never felt so —— AAAAHHHHH!!! All because of yet another movie. A resplendently photographed depression-case stinkbomb designed to hurt. How could I possibly praise Melancholia as a distraction? I don’t need to. People will see it, and they will be affected if they can get past the unpleasantness (us Bergman and Cassavetes folk have a leg up). To what end you say? To the end. Somebody went and made a truly satisfying tome about it. There was a refreshing freedom in the harshness employed here. Whatever Roland Emmerich might think, no one need take in this subject in a well-rounded, side-road-providing way. It surely won’t be taking you in this fashion.

• Melancholia: http://www.melancholiathemovie.com

• Magnolia: http://www.magpictures.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2gxm

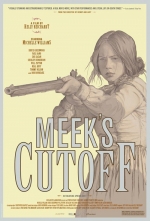

03. Meek’s Cutoff

03. Meek’s Cutoff

Dir. Kelly Reichardt

[Oscilloscope Pictures]

With her fourth feature and first period piece, Kelly Reichardt maintained her position as a major talent in American cinema with Meek’s Cutoff. She and writer Jonathan Raymond applied the stark aesthetic of their previous collaborations, Old Joy and Wendy and Lucy, to a frontier tale that refused to settle into conventional rhythms or permit easy identification with its characters (played, without a trace of egotism or self-consciousness, by a small cast led by Michelle Williams and an almost unrecognizable Bruce Greenwood). Instead, the snatches of overheard dialogue and shots of pioneers dwarfed by desolate landscapes was like peering through a peephole at the Oregon Trail in 1845. Meek’s Cutoff was a demanding film — it risked boring audiences, and in many cases, it did. But patient viewers were rewarded with a rich experience that built tremendous intensity as it progressed. By the ominously uncertain finale, the film’s title had assumed endless and paradoxical meanings involving power dynamics and sudden endings and divergences. With mythical, Biblical suggestiveness, Meek’s Cutoff placed Manifest Destiny within the whole history of human hubris and greed, but this haunting film’s avoidance of nostalgia and anachronism made its sexual, racial, and political implications all the more powerful and complex.

• Meek’s Cutoff: http://meekscutoff.com

• Oscilloscope Pictures: http://www.oscilloscope.net

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2er3

02. The Future

02. The Future

Dir. Miranda July

[Roadside Attractions]

Miranda July certainly took her time to present us with a new feature film, and, love it or hate it, The Future was filled with all the eccentricity one has come to expect from a filmmaker who manages to stir bouts of rage and cries of praise in equal measure. Paw Paw, a soon to be adopted stray cat, was the improbable catalyst for the personal crisis that will have the thirty-something couple Sophie (Miranda July) and Jason (Hamish Linklater) delve into a bizarre personal journey once they’re faced with the fear of the responsibilities that the new animal promises to bring. Despite the typical July cuteness (there is a narrating cat, after all), The Future had a remarkably different tone than her 2005 debut (Me and You and Everyone We Know), constructing itself as a far more serious, darker, and grimmer experience. The director’s mannerisms here all seemed to serve a higher purpose and did a great job of conveying the film’s central conflict between the desire to fully explore life and the inevitable anguish of being confronted with such overwhelming freedom. The Future certainly made for a bleak and cerebral experience, and if you could look past some of the annoyances and excessive quirkiness for which July has come to be known, you’d find one of the most thought-provoking and narratively ambitious films released this year.

• The Future: http://thefuturethefuture.com

• Roadside Attractions: http://www.oscilloscope.net

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2go5

01. The Tree of Life

01. The Tree of Life

Dir. Terrence Malick

[Fox Searchlight]

Like many filmmakers, Terrence Malick likes to ask big questions. But unlike most of his contemporaries, he’s really, really upfront about it. A major proponent of voice-over narration, the director often layers the voice of one or more characters over a montage of fleeting events, a life in constant motion, eschewing conventional exposition to present human beings in uneasy transition. And in The Tree of Life, Malick made a grieving Mother (Jessica Chastain) whisper, “Who are we to you? Answer me!” as we watched a scientifically accurate rendering of the formation of the cosmos. At that point, it was enough to make a lot of people walk out of the theater. Maybe they hadn’t seen Malick’s other movies, which are some of the most palpably transient narrative films ever made, where moral uncertainty is always ameliorated by spiritual harmony, emphasizing the preciousness of moments when perspective is still open-ended. Or maybe they realized this wasn’t just some movie about a family living in 1950s Waco, Texas.

Indeed, though they took up most of its running time, The Tree of Life wasn’t entirely about the O’Briens; their surname isn’t even mentioned in the movie. In fact, we only learned where they live about halfway through the film, labeled on the side of a moving truck, spraying clouds of DDT over neighborhood lawns, a dozen children dancing and laughing in the white smoke. It’s one of many images in the film both ethereal and unsettling, not just because of its aesthetic rush, but because of the fantastical images that immediately preceded it: a boy hiding in an empty grave, a mother laid to rest in a glass casket in the middle of the woods. The reciprocation of life and death, of memory and imagination, are hardly new themes for Malick, but they were never as variegated or as fluidly depicted as they were here. In his fifth film, the director gave us not just another celebration of human experience, but a thoroughly detailed, impressionistic, uncanny portrayal of how that experience forms into long-term knowledge, often transcending it in the process.

By elevating one man-child’s story to cosmic proportions, Malick’s film was so thoroughly, unabashedly self-absorbed that it dared us to return to childhood ourselves. It recreated a time when one sees and hears many things, mostly forgotten or saved unconsciously to rediscover later. In miming this process, Malick began with an explanation of the ways of grace and nature, only to transmit them through various voices and guises, splintering and interweaving through long, often fragmentary sequences. With aggressive and elliptical editing, Malick created a dialogue of associative imagery: certain characters appear for minutes or mere seconds, or hang in the background as if in peripheral vision; many small incidents occur that occasionally seem plucked from whole other movies themselves. It’s almost fitting that the film ends stumbling through the gates, ladders, and paved paths of an alternate reality — Malick’s first foray into the supernatural — threatening to derail everything that came before it. (As if the rest of the film wasn’t set on confronting objective reality.)

By interrogating the universe, The Tree of Life proved to be Malick’s most profoundly anti-cynical and vulnerable film yet, a combination that doesn’t sit well in our increasingly self-conscious, jaundiced culture. As a result, no other film this year was as fiercely debated or scrutinized. Yet the film stood out in an incredibly strong year for movies overall, not simply for its ambition, but for its generosity. At once kaleidoscopic, personal, and unhinged from convention, Malick’s unwieldy epic consistently rewarded our imaginative sympathy.

• Tree of Life: http://www.twowaysthroughlife.com

• Fox Searchlight: http://www.foxsearchlight.com

• TMT Review: http://tmxt.es/2g7u

[Artwork: Keith Kawaii]

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series