We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

STATE OF THE UNION

This was the year of girls on American television. There was the literal Girls, New Girl, and Two Broke Girls, as well as The Mindy Project. These all boast women as showrunners and creative driving forces: Lena Dunham, Liz Meriwether, Whitney Cummings, and Mindy Kaling. If the shows themselves range in quality (guilty pleasure? critical darling? ugh?), the force of their presence in 2012 was undeniable. But where are the American films directed by women? Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty makes a late entrance in December, but otherwise they’ve been few and far between this year. Those television shows all happen to be comedies, and three of the four above-mentioned women are also actors. It seems that room has been made in entertainment for self-propelling dynamos who write, direct, and star in their sitcoms. But what about the women who’d rather be behind the camera? Why aren’t more women directing films?

In summing up the year’s “best,” I try to include women directors whenever possible, but scarcity is an aggravating fact. It’s a bright year when Nicole Holofcener (Please Give) or Lisa Cholodenko (The Kids Are All Right) release a film, and I’m eagerly waiting on whatever Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone) and Kelly Reichardt (Meek’s Cutoff) will do next. There were a few strong releases this year, including Sophia Takal’s Green, a woozy drama about jealous lovers, and Lynn Shelton’s clever sibling rom-com, Your Sister’s Sister, with Emily Blunt and Rosemarie DeWitt gamely matching Mark Duplass’ improv skills. Both of these films made brief appearances, but unfortunately, neither ignited attention or conversation the way I hoped they would.

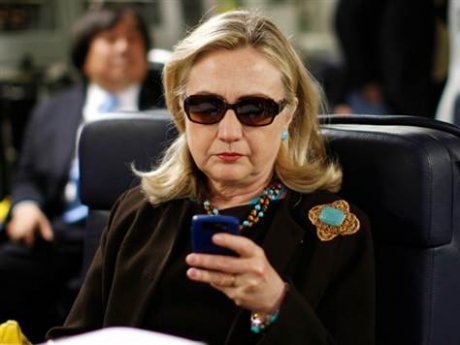

The end result is that, in this pissing contest of an election year, the most iconic images of powerful women came from politics. Television can keep its girls; I’ll take Hillary Clinton texting and Michelle Obama flexing her Linda Hamilton guns. These images tell a much more interesting story about women and power than girls eating cupcakes in a bathtub.

THE A WORD

Auteur theory comes initially from the French critics, most famously François Truffaut, who wrote for influential film journal Cahiers du Cinéma. From their mid-century vantage point, they had an at-the-time novel perspective on American and Hollywood directors, arguing that some of those directors, rather than being commercial cogs in the machine, were actually the film’s authors, overcoming the industrialized, mechanical nature of filmmaking to imprint their work with a distinct style. Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris (who died this year, RIP) brought auteur theory stateside, elaborating on it in essays and in his book The American Cinema. This kicked off a debate about auteurism that still continues, but auteur theory has always resonated with me. I respect experimental filmmakers who work in the margins, but I’m fascinated by directors who work within the system. That takes a very different, almost Darwinian, skill set. Sarris puts it well when he writes, “the auteur theory values the personality of a director precisely because of the barriers to its expression… The fascination of Hollywood movies lies in their performance under pressure.”

I’m not arguing that women rising in the ranks of television isn’t exciting. I love a lot of the work that’s being done in television right now, especially some of the writers and actors who are emerging in that medium. The cinematic language of Breaking Bad can rival vintage Scorsese for visual storytelling (see: the Crystal Blue Persuasion montage from season five). Television also seems preternaturally built for social media platforms like Twitter. If you didn’t watch Breaking Bad, Downtown Abbey, Louie, The Walking Dead, or, yes, Girls, you couldn’t be a part of the conversation. Can I really say that about any film from this year? Film arguments seem to be increasingly for the converted — e.g., fanboys and critics scuffling over The Dark Knight Rises reviews — while I had to go full ostrich on nights when my shows aired (hint: avoid Diplo’s Twitter feed). This doesn’t change the fact that the hunger for good movies is still there. I get something from films that I can’t get from an episodic television show. Bending a character to the conformed arc of a feature film yields a kind of potency of character and a distilled sense of transformation. To borrow from T.S. Eliot, films “have the strength to force the moment to its crisis.” The elongated timeline of television, while immersive and addictive in its own way, doesn’t have the force of an epic film.

While women directors remain underrepresented, the 1990s boy’s club of talent is still going strong, proving remarkably resilient to the slings and arrows of Los Angeles. This year saw the release of new films by the Andersons (Paul Thomas and Wes), Steven Soderbergh, and David O. Russell (with the Don, Quentin Tarantino, unveiling Django Unchained in late December). In other words: long, flourishing careers. Although the dissonance in opportunity for women directors is frustrating, it doesn’t change the fact that I really liked the new work by the old guard. Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike, and Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master were notable films in terms of marrying visual style with narrative content. I don’t have a very good memory, and these are films I remembered specifically, and continued to feel something for, long after I had seen them, their imagery and characters impressing themselves upon my memory.

If these worlds are dominated by male characters, there was something surprisingly, but unmistakably, vulnerable about them. These directors have created insular, self-referential worlds, with narratives that don’t thrust as much as they rise and fall. While the girls on television have a glib, modern sort of toughness (despite their quirky, perky, and snarky fronts), the “heroes” of these auteur films seem more unsure and conflicted about who they are. A closer look at these films reveals interesting differences in their depictions of manhood.

• The Boy

From Wes Anderson’s “Moonrise Kingdom”

From Wes Anderson’s “Moonrise Kingdom”

The rhythms of life in Paris seemed to have gotten under Wes Anderson’s collar. Moonrise Kingdom had a certain Gallic je ne sais quoi, and the film shook off some of Anderson’s prim tendencies. This wasn’t immediately on display in the opening scene, where we were introduced to Suzy Bishop (played by newcomer Kara Hayward). Suzy was Margot Tenenbaum redux, glaring at us from under eyelids heavily shadowed with blue. In collared dresses and saddle shoes, Suzy lingered on the divide of girlhood and willful womanhood. She met orphan Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman) when he wandered backstage at a performance of Noyye’s Fludde, or Noah’s Flood, an opera by English composer Benjamin Britten (along with Hank Williams, Britten’s music comprises a prominent chunk of the score).

Sam and Suzy’s inevitable choice to run off together sent the adults into a kind of slapstick panic, revealing more about their own fears than about any real danger the young innocents faced. Suzy and Sam forded small rivers and hiked up cliffs, like Adam and Eve searching for Eden in reverse, and Anderson lit these scenes with golden sunshine. But like most boys, Sam fumbled at his good luck: once he had Suzy, he didn’t know what to do with her. I wasn’t initially sure where Anderson was going with this sequence, and its length made me a bit impatient, but when Sam and Suzy finally reached their destination, an idyllic cove by the sea, the film’s tone completely changed. In retrospect, Anderson’s pacing is what built the tension and allowed for the payoff.

Like a budding Jean Seberg, Suzy brought along only music and books, which she laid in front of Sam like an offering. Between the French yé-yé pop and the rolling waves, Sam and Suzy’s relationship veered from childlike innocence to frank sexuality. From the cutaway to a swan, to Sam piercing Suzy’s ears with fish hooks, the whole sequence had an erotic charge, consummated as they kissed in the water. The frazzled parents arrived by boat the next morning to find Sam and Suzy in their underclothes, locked in each other’s arms.

This sequence by the sea was by far the film’s loveliest. From there, the film moved along at more of a clip, driven by the approaching storm and the film’s plot. Like all of Anderson’s recent films, Moonrise Kingdom occasionally had the fussiness of a meticulously designed tableaux. The film equated Sam and Suzy’s adolescent love with the force of the storm, and in the third act, the film gave itself over to this metaphor. By externalizing the sturm und drang of Suzy and Sam’s passion, the device of the storm had a chastening effect on the film. The adults of New Penzance had a melancholy, curiously sexless quality, which was what made the lust and desire of Sam and Suzy’s first kiss feel so startling.

In the final scenes of the film, Anderson’s tracking shots again revealed the Bishop house to us. As with its opening, the film ended with a piece from Benjamin Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, this time defining a fugue. Childrens’ voices cued the various instruments as the music built in intensity. It was a fitting finale, perfectly recalling the storm of lust that engulfed Sam and Suzy. “Sudden unexpected travel away from home”? “Confusion about personal identity”? What is adolescence but an extended, dissociative fugue state?

• The Beefcake

From Steven Soderbergh’s “Magic Mike”

From Steven Soderbergh’s “Magic Mike”

I love Steven Soderbergh for giving a damn about what the ladies want. How else can you explain Magic Mike, a film with a trailer so relentlessly corny that I thought it was a joke? That’s because the trailer cut out all of the depressingly measured realism that tempered the film’s supposed glamour (hint: we’re in Tampa). Whatever bizarro motivations actually drove Soderbergh toward Tatum’s gyrating torso, I applaud the choice. And so did the theater full of women who turned up for the film when I saw it. Like over-caffeinated fanboys to the flame of The Avengers, these ladies swigged wine and hollered at the screen, ready to be entertained.

Magic Mike turned out to be not only a good movie, but also an insightful one. Between chances to show off irrepressibly suave moves on stage, Tatum’s stripper Mike’s life was glumly mundane. His biggest aspiration was to run a small business — Mike’s Custom Furniture Concepts — for which he’d build original, handcrafted furniture. We saw Mike wielding his tools in both his roofing business and most obviously on stage, but never in a workshop. The evidence of his talent was a futuristic chrome-and-glass coffee table that made for some nice morning-after chatter with the threesome partner he had on speed-dial. Mike claimed the table was built from debris salvaged after a hurricane, but the hulking metal looked distressingly like an airplane propeller.

From Steven Soderbergh’s “Magic Mike”

From Steven Soderbergh’s “Magic Mike”

Mike was a self-professed entrepreneur, the manager of several cash-only businesses, but no suit and tie would get him a decent loan from the bank (Why doesn’t he try Etsy?). But his talent on stage was undeniable. The funnest part of the movie had to be the choreographed stripper routines, where the athletic dancers of Xquisite Male Dance Revue aped every traditionally masculine career in the book: firemen, soldiers, construction workers, cowboys, boxers, Tarzan. A hilariously campy Matthew McConaughey played the club’s owner Dallas, and when he asked the ladies to “make it rain,” they couldn’t empty their clutch purses fast enough. Along the way, Mike picked up a protégé Adam (Alex Pettyfer), whom he called the Kid. All it took was one night out with Mike and Adam’s converted. There was even an ersatz baptism, as Mike and the Kid flipped off an overpass into the waters below. The lifestyle offered “women, money, and a good time,” according to “stripper wisdom.” What’s not to love about that holy trinity?

Magic Mike was a strange hybrid, a dull script shot by a talented director with visual precision. Soderbergh had a great eye for the spaces he was in and how to move in them, especially the muscular dance sequences in the club. But for all of his charm, Mike was a bit slow on the uptake. He practically walked himself in circles trying to talk to the Kid’s civilian sister Brooke (Cody Horn, who appeared to be chewing a mouth full of marbles for most of the film). It took him most of the movie to realize that Dallas was hustling him out of money on a new club in Miami. In the end, what made Magic Mike so interesting was its failure to give its hero a triumphant ending. What does it mean when “the Sexiest Man Alive” tells you to lower your horizons? There is the suggestion that, beneath the orgiastic partying and superficial good looks, stripper wisdom isn’t such a good time after all. But Magic Mike was a recession movie, and its arc was driven by economics rather than morality. It revealed Mike’s reality for what it was: a stucco jungle with palm trees, not the promised land.

• The Captain

From Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master”

From Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master”

For all the talk of Scientology, P.T. Anderson’s The Master wasn’t a religious film. The cult it deconstructed was the cult of manhood. Anderson had distilled two essences of masculinity into Joaquin Phoenix’s drifter Freddie Quell and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s sect leader Lancaster Dodd. Women hovered on the edge of the frame, but the film was about the intense bond between the two men at its center.

The opening sequence of the film recalled Freddie Quell’s final days at sea during World War II. We saw Freddie hack coconuts from a tree with a machete, all but castrating it. A beat later, he talked about shaving his testicles to rid himself of crabs. A shirtless group of men wrestled on the beach. They built a woman out of sand, nipples erect and legs spread, and Freddie groped her like a prostitute. And this was just the first few minutes of the film. When a V.A. psychologist examines him, Freddie saw only genitalia in the Rorschach inkblots. Yet despite their reservations, the authorities loosed him upon the world, and Freddie disappeared into the stream of broken men returning from battle.

Freddie found work as a portrait photographer at a department store, where he distilled his poisonous homemade spirits in the darkroom. But he had a restless, brawling quality, an untrammeled instinct that pushed him into conflict. It was unclear whether Freddie was traumatized, mildly psychotic, or both, but that job didn’t last long. In a gorgeously shot sequence, Freddie accosted one of his subjects, a husband sitting for a portrait for his wife. They wrestled in the store, sliding on the marble and smashing crystal into shards, while the camera tracked alongside Freddie, following him as he made his escape.

From there, Freddie drifted West and ended up harvesting cabbages in dusty fields. The first shot of this short sequence showed Freddie slicing cabbage from the root, recalling the earlier castration of the palm tree. Freddie’s liquor sickened an old man, and he was accused of trying to poison him and run off the farm. As Freddie flew through the cabin’s door and into the fields, the camera stayed framed on the doorway, as we watched him recede in our view. The film then cut to a marvelously kinetic tracking shot that followed Freddie as he ran for his life along the furrows of the earth. The Master was full of such beautifully composed images. As has been widely noted, it was shot on 70mm, a large-format film stock. Whatever complex technical mastery contributed to it, the film was luminous, the colors rich and unbelievably nuanced, lit like a Rembrandt painting. It was easily the most visually stunning film I had seen this year. Sure, the story skittered to a close, without the hellfire confrontation of There Will Be Blood, but I still found it enthralling.

From Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master”

From Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master”

Adrift once more, Freddie wandered by a dock. He saw a boat lit in the darkness and went onboard. This vessel turned out to be carrying a group of believers and their leader Lancaster Dodd, and Freddie awoke to find himself on his way to New York. The first words he hears were soothingly uttered to him by a beautiful woman: “You’re safe. You’re at sea.” This could’ve been a mantra for the film, which found richness in the emotionally unmoored state of its men. Freddie was brought to meet Dodd, who we immediately see was his opposite. For all his wiry aggression, Phoenix was diminutively thin, his lined face all angles. In the sequences between the two men, the film cut repeatedly from one face to the other. Anderson saved his closeups for the topography of their forms, Freddie’s dark edges versus Dodd’s well-sated pink flesh.

Through the course of this first journey, Dodd began to submit Freddie to processing, which was a probing, psychological form of questioning. Under Dodd’s intensely intimate gaze, Freddie cracked open, spilling tears as he remembered his mother and first love Doris. It was the first we really learned of Freddie in relationship with another person, and it humanized his character. Dodd became fascinated with Freddie and his “flask of secrets,” and enlisted him as a sort of companion, despite the protests of his wife and daughter. Dodd called himself the captain of the ship, a designation that’s echoed throughout the film. He began to steer Freddie into the movement he leads, named The Cause. The creed was vague, but gatherings of Dodd and his believers involved group therapies and discussion of past lives. They eventually forced Freddie to submit and try to teach him to tame his impulses.

In their final meeting, Freddie visited Dodd in England, where the persecuted group had settled. If Dodd was the captain, then Freddie was what he called a “sailor of the seas.” Dodd was wistful when he told Freddie to “go to that landless latitude,” though the freedom he ascribed to Freddie’s life was a delusion. The captain-sailor dynamic was the fanciful way that Dodd would like to imagine the two of them, the twin poles of savage darkness and civilized light. But the scene that best encapsulated Freddie and Dodd was far more basic than that. In an earlier scene, Dodd was charged with fraud, and Freddie, roguely acting as Dodd’s muscle, attacked the police officers who came to arrest him. Both were taken to jail and locked in adjacent cells. Freddie went ballistic, throwing his body around the cell, breaking the toilet and swearing at Dodd, who eventually shouted back. Anderson framed the scene behind bars, showing us both men at once: intellect and impulse raged at each other on either side of the wall, but they were both locked in the same cage.

THE VESSEL

In a trend that revives every few years, there was a spate of critical writing predicting a sort of end-days for film as an art form. They are laments, funereal dirges for the talent and artistry that once was. I don’t entirely disagree: I will miss film stock, which seems to be going the way of the dinosaur. But filmmakers are resilient, and if they are driven to extinction, they’ll at least put up a good fight. In a recent article in the mournful vein, New Yorker film critic David Denby issued this tepid encouragement: “There is enough talent sloshing around in the troubled vessel of American movies to keep the art form alive.” While the establishment will hopefully soon also include women directors prolific enough to be canonized as auteurs, this year that sloshing talent includes the established male auteurs I’ve discussed, who made incredibly relevant and deeply memorable films in 2012.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series