We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

40. Lil B

White Flame

[Self-Released]

My favorite quote of 2012: “Underground music, n****. I don’t want to make it.” The lyric completely outlined the composition of Lil B’s White Flame as a vessel of himself. Mariah Carey became a fine-tuned human-musical instrument, and Lil B has become the perfect 21st-century artist. Mixing satirical rap, self-deprecation, hyper-aesthetic marketing, trans-lyrical personification, and digital-deep emotion brought White Flame to that level of “I’m so self-conscious about my art work I’ll make it exactly about that. Oh, and hide it in the cheesiest pseudo-spoof mixtape, but keep it completely nostalgic on a Based level. And now I’m talking as Lil B the BasedGod as C Monster. It must be all that BasedEnlightenment I’ve been experiencing while listening to White Flame on random through three different media players.” Yet, it’s really hard to describe Lil B without quoting him — err, his work. So here’s the skinny: for TMT’s Chocolate Grinder section, I usually listen to a single track anywhere between five to [feels like a milli] times a day, but I can listen to White Flame on repeat forever. Thus, this stamp in the Lil B timeline, I feel, was his most important in 2012. “White Flame ain’t no joke.”

39. ahnnu

pro habitat

[WTR CLR]

Conceptually and musically, ahnnu’s pro habitat created its own environment, one that depended heavily on preserving the habitats of his decaying sound sources (vinyl crackle, tape hiss) alongside orchestral crescendos, broken soul samples, and slurred jazz noises. While many beatmakers seek to isolate the parts of sound that they wish to use in order to repurpose it for their own music, ahnnu took a step back, analyzed the way the multiple layers of a song or sample existed together as a complete habitat, and boldly used all of it, suggesting an unbroken flow of similarities spreading between genres, locations, and time periods. The result was so smooth, so natural that it was impossible to imagine the size of the spectrum of varying musical habitats from which the source material was pulled. So, when “canopoli” rang in and a sampled voice suggested that “the music should be barely noticeable… and non-distracting,” it was like ahnnu was imagining a future of sample-based music portrayed by a smooth, painted landscape, rather than one assembled from puzzle pieces.

38. Ian Martin

Mechanical Rain

[Further]

From the very first moment of “Moving Activity,” I felt a chasm open up within me, gut-wrenching, head-sinking, chest-thumping. In all honesty, this hadn’t happened to me in six or seven years, back when I first heard “Everyone Alive Wants Answers” from the album of the same name by Colleen. As did that album, Mechanical Rain started from perfectly configured initial conditions and spun inward, onward, unfolding, it seemed, according to nothing less than absolute necessity. It made me feel alone, but in a way less sentimental than plainly truthful. It wasn’t exactly easy to listen to the desolate intricacies of Ian Martin’s two synthesizers, but it was a lot harder to not listen. I found the album demanded my attention without forcing my attention. It lay me out supine and closed my eyes, yet it refused to let me fall asleep. Call it “meditative” as long as you understand meditation as a discipline of the attention, as the ability to follow the objects of your mind without encouraging any of them to mislead you. Mechanical Rain was un-ambient: it didn’t sink into the background but rather became the background so that the background could become foreground. I listened to this music not to look at rain as weather, but to see rain as (strange, mechanical) rain.

37. Tame Impala

Lonerism

[Modular]

Kevin Parker has fully dispelled any lingering pretenses to the low-pass production filter de rigueur by so many of today’s psych revivalists. Lonerism’s purchase on solitude, what with its superabundance of reverb and wealth of manicured synth banks, owed more to Rick Wakeman sonic excess than Erickson angularity. Still accessible but short of anthemic, Fridmann’s maximalist hand on the stern suited Parker’s preference for texture over linear progression. Lonerism presented a giddy mood of teenage exceptionalism, that die-cast sense of me-apart-from-the-world. And yes, it was one to be indulged in, whether it was shamelessly air drumming to the flanged fills à la Steven Drozd or giving a quarter crank to the volume knob as “Music to Walk Home By” recapitulated its forward momentum. Maybe Tame Impala’s abiding anachronism lied beyond their retinue of driving pentatonic riffs, boutique fuzz pedals, and Beatles-esque psych ramblings; Parker’s latest embrace of studio wonkery and overdub indulgence hinted at an ideal of bedroom isolation predating our impulsive connectivity. In those moments, when we were caught chewing on the crumminess of the world, there were worlds to be lost in — not networks or directories. Lonerism is one to pull from the stacks 15 years down the line after pulling your dad’s speakers out of the basement.

36. The Men

Open Your Heart

[Sacred Bones]

“Evolved,” “changed,” or even “softened” might be words you had heard/read regarding The Men’s Open Your Heart, but their MO is the band’s driving force, and that for all intents and purposes was what had truly improved. Beyond their sound, quotable approach, and penchant for direct riff-rippage (Stiff Little Fingers, The Buzzcocks, and Sonic Youth, most notably), Open Your Heart showed a band in a classic state of personal and professional growth, while also showing that rock ‘n’ roll’s traditionalism could be just as exciting and sincere as the bands and moods they had appropriated. From the addition of slide guitars and an acoustic ballad, The Men looked to rock’s past in order to find an outward reflection of themselves and their intentions. Open Your Heart was not about reinvention, revivalism, or bringing back punk to the masses. It was about how playing with repetition, the past, and the present shapes meaning. The Men aren’t saviors; punk rock can save itself. Or as they put it: “We’ve never been a band that was part of anything.” Indeed, Open Your Heart was about something bigger than rock ‘n’ roll’s life status.

35. Burial

Kindred [EP]

[Hyperdub]

Burial likes to shroud himself in secrecy, the better to spin those threads that comprise his all-consuming worlds of sound, those little miracles that conjure up your most dangerous, most secret emotions. Such was the dark magic of February’s Kindred EP. Deeper and more textured than any Burial release before, Kindred not only captured the essential isolation and beauty of city life, but also made you want to wallow in it. Second track “Loner” immersed the listener in a soundscape where hope was twinned with despair, and once its seven and a half minutes were over, you were genuinely surprised to look out the window and see sunshine and palm trees rather than rain streaming down the windows of a junker car parked beneath a bridge near the docks. Critics drooled over the fact that tracks like “Ashtray Wasp” and opener “Kindred” came closer to dance-floor staples than any Burial release before, and why not? It’s only natural that, after Burial guided you into the heart of darkness and out again into the light, you’d wanna throw your hands up and celebrate the sensorial wonders of the human experience.

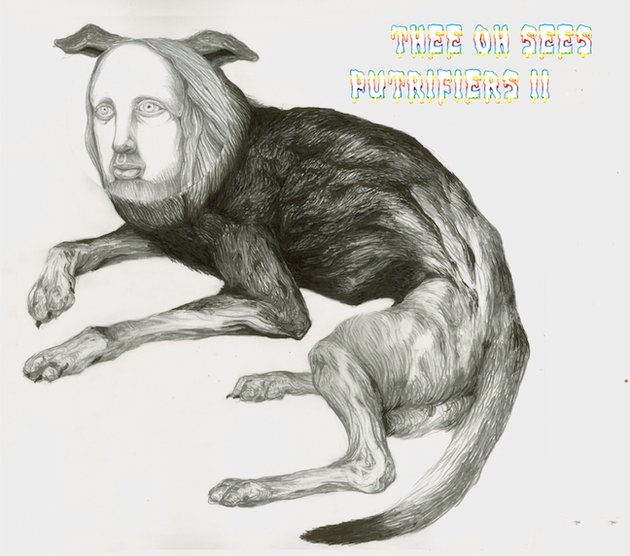

34. Thee Oh Sees

Putrifiers II

[In The Red]

Rather than putting his energy into coming up with a new genre or pushing some crazy personality to generate hype, John Dwyer unashamedly focuses his Thee Oh Sees project on 1960s garage psychedelia. Although perhaps not adding much to the critic repertoire of genre prefix and suffix shuffling, what he and his collaborators presented with Putrifiers II was a shining example of how to channel the raw garage power of The Monks, The Sonics, and the experimental composition of The Velvet Underground while maintaining that glint of newness, of a clear and present danger that made garage rock so compelling to youth and scary for adults the first time around. This album was not a mere anachronistic exercise. Bolstered by a renowned ability to perform live, Putrifiers II had a sense of immediacy to it that could not be faked with all the Pro Tools tweaks in the world. Awash in distorted guitar lines and heavily processed vocals, the pure jams of “Lupine Dominus” and the opening track “Wax Face” could make believers of anyone willing to listen. Sure, its forms may have been familiar — parallels could be drawn from “So Nice” to VU’s “Venus in Furs” or “Wicked Park” to Syd Barrett — but the energy that fuels Thee Oh Sees burned as hot upon their 2012 release as it ever could have.

33. Farrah Abraham

My Teenage Dream Ended

[Farrah Abraham/MTV Press]

Hoping to spark a critical debate on what exactly makes a piece of art good, former director of the Tate Modern Will Gompertz recently wrote an editorial making a plea for a major museum to stage an exhibition of works from its collection that it deems to be bad art. Just let them try to acquire Farrah Abraham’s My Teenage Dream Ended on behalf of The Museum of Bad Art; Abraham’s disorienting album fearlessly confounded every playlist and exhibition into which it was dropped, even as debate among critics continued and The Museum of Outsider Art came knocking. There was so much here: tortured echoes of tabloid sound-bytes, reality TV confessionals, and pop’s faked climaxes, but as Abraham said, “I can only put so much in a song.” For us, it wasn’t how much she had put in, but how deep she had buried it — all of it ratcheted by Auto-Tune and ribboned by churning bass riffs, both dramatizing and plowing under the album’s tortured backstory. The year’s most compelling narrative, sonically and otherwise.

32. Motion Sickness of Time Travel

Motion Sickness of Time Travel

[Spectrum Spools]

By design, free-form drone music usually doesn’t come packaged as a big statement. It’s usually doled out little by little on CD-Rs, cassette tapes, and 7-inches. This kind of experimentalism seems meant to be absorbed in small bites, each one a beta test of a still-evolving sound. Although her sound is still developing, Rachel Evans achieved something of a watershed moment with this record. As she mentioned during an interview from May, the album’s gestation period saw it develop into a surprisingly self-sufficient statement. It is self-titled, it’s a double LP, and, as she told Jonathan Dean, ” I felt like the finished product was a good representation of where I’m at right now with [Motion Sickness of Time Travel]. In that way it is a definitive statement…” In terms of pure aesthetics, the album was a blanket of bliss. Evans had the courage and patience to allow moods and moments to develop at a glacial pace, clearly feeling the freedom to stretch out over nearly 90 minutes of recorded material. She also had the compositional ear to create beguiling layers of twinkling arpeggios and shimmering oscillations. These served as ripples within the vast waters of her sound, until the listener felt totally enveloped beneath the waves. What remained was a picture of an artist totally in love with her synthesizers, totally in love with the process of methodically building her tracks, and totally in love with drone.

31. Jason Lescalleet

Songs About Nothing

[Erstwhile]

Cynically designed and morosely brimming over with sooty diamond-crusty apathy, Jason Lescalleet’s Songs About Nothing nonetheless thrilled and enticed as one of 2012’s most euphorically ear-opening experimental works. The mastery of a suspenseful atmosphere drove each of its 13 environ-peeping sections before it dropped you square in a glorping body-high bog of eternal squenche. In addition to it being the masterpiece of queasy abstract voyeurism that it is, there was a radiance-imbuing quality to this album. It was like a ratty old blanket you pull over yourself and dream roving desert dreams of a reckless peace and an ever-changing light at the bottom. You sense it’s there, but you are too terrified to look and take stock. Such was the way of it here. Songs About Nothing was the best horror film of the year, for years. It was a well-curated museum of breaking down, a murky stand of mottled black windsocks whipping about between two receivers. The sample circled arguing with the microscope. Time squeezed tight and flexed.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series