We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

Truculentus, Evermore

Death has always been both simultaneously feared and celebrated. Despite its impending, indiscriminate nature, death grips the imagination and manipulates social norms, reshuffling furniture inside the mind, toppling concepts of awareness on a plethora of existential levels, and realigning aspiration for artistic construction. Indeed, death has infested creativity worldwide. World events, personal experiences, and ravenous outbreaks that cause such inspiration have the potential to trigger shifts in the appreciation of works disseminated across an encompassing array of forms; from sculpture, graffiti, and shrine arrangement to pottery, origami, and music. A key issue at stake here is the expressive value of craft pertaining to deathly themes, and it is through discussing its representation via parafocal lenses of the macabre — the ghastly and horrifying — that I think is worthy of investigation, especially in a year in which death has continued to be such a central focus in the arts.

But how can that be measured when there is no means of quantifying an enthusiasm for such discourse throughout media output in a single year? Particularly when identifying exactly what “media” constitutes has become so awkward, from subverted news broadcasts about anti-Islamic films that invoked horrific religious rebuke, to the very content of those stories channeled through a range of different platforms that encompassed both individual and multinational distribution points. Circulation formats aside, a persistent fascination for death has ceased to dwindle as a consequence of technological development or the indirect, quasi-communication strategies that allow for terminological redefinition to continue, and the 37,000+ search results for “funeral” on Instagram encapsulate a number of biting indicators.

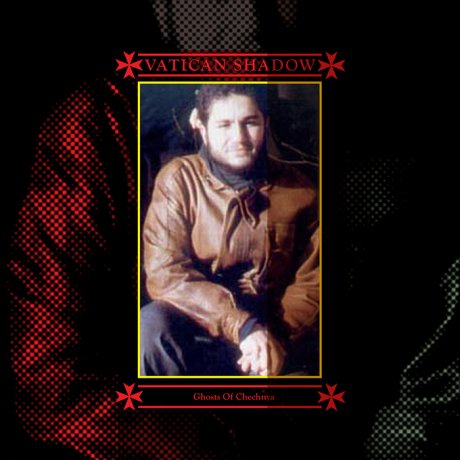

In the music world, the new year was christened by a bold reenactment, an homage to one of the most grim and sorrowful compositions of the 20th century with unrelenting death and torture at its center. Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima was revisited in a collaboration between the Polish composer and Jonny Greenwood in a fascinating production that illustrated passionate sympathy through symphony, a mourning for the casualties of nuclear fallout. All the while, the very subject of nuclear proliferation occupied pertinent space in the headlines, as contenders battled diligently for their right to stand poised over a metaphorical button that could unleash similar situations elsewhere. The true extent of the damage, or even the value of such detriment, constantly hung in the balance of public debate, while at the same time, images of militants, insurgents, and soldiers splattered one of the year’s most prolific underground electronic artists’ album sleeves. Artwork that embraces the macabre tends to express an interest in death and decay on the artist’s behalf. As a focal point, it might be used to release tension or exemplify contemplation, allowing for factors that remain both inevitable and unknowable to creep into the audience’s line of vision.

Cover art for Vatican Shadow’s “Ghosts of Chechnya”

Cover art for Vatican Shadow’s “Ghosts of Chechnya”

The films and music that chose to elaborate on death as a linchpin in 2012 were particularly common, making for a compelling springboard into discussion here on a number of issues, not only concerning warfare and politics, but also with regards to presence and atmosphere. That’s not to take matters of international significance lightly, but to stay as indiscriminate, trivial, and slapdash as the paintings that spurred this rather murky retrospective — from the heinous depths of Vatican Shadow, to the dismal and harrowing music of Locrian, Mamiffer, Penderecki and Greenwood. Along the way, visitation rights are also granted to Emmanuel Nunes, Josef Škvorecký, and Kaneto Shindo, three pioneers of bleak and abstract works adhering to macabre themes, who passed away earlier in 2012 — for their efforts contributed substantially to this ever morbid tapestry that has continued to spin uninterrupted since its most gruesome beginnings.

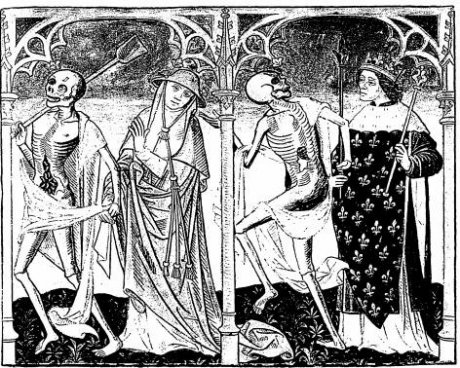

Death’s Unity Lies Not in Its Origins

In 1348, a trading ship arrived at Dorset after setting sale from Gascony. Along with its humble cargo, the vessel carried an abundance of fleas, xenopsylla chopis, contaminated with the Yersinia bacterium that instigated an outbreak of concentrated human infection and ultimately a pandemic, which claimed an estimated 450 million lives worldwide. Over the course of a hundred years or so, creative forms were implemented as a method of chronicling the events at hand in addition to bringing about a broader illustration of unity, through eternal rest, that was most iconically portrayed in the Danse Macabre. The concept, part of an artistic genre of The Middle Ages that depicted the universality of death, has been persistently recreated since its first portrayal in 15th-century France, but what the imagery fundamentally eludes to is the unquestionable impartiality of death. In its various incarnations, cadavers summon the old, the young, the rich, the powerful, and the poor, who are all called to take part in this posthumous ceremony, a jovial dance in the face of mortality that seals the fate of every living being.

Artistic works, particularly in painting at the time of the initial outbreak, ravenously documented scenes of lawless behavior, extreme licentiousness, and mass graves. Though there was little immediacy in capturing public imagination, death became a rampant subject through inventive expression that was a massive departure from the elaborate glory of Christ’s crucifixion towards austere visualizations that transcended into breakaway behavioral traits. Commemoration became a theme in the British Isles, while sadomasochism erupted throughout Germany and persecution took on assorted manifestations elsewhere in Europe. These reactions were by no means an upshot of expressive artistry, but an actual portrayal of the physical situations that governed during this devastating age. However, the art that blossomed as a consequence assumed radical steps in the way that death is depicted artistically, and it has not been the same since.

The images and music that thematically placate these subjects invoke a cacophony of emotional backlash, which varies as much as those 14th-century social retaliations to the plague itself. Penderecki’s Threnody is an enthralling example of this, not only because the original caption for his piece was “8’37″,” a title void of any affiliations of death, reminiscence, or anything at all other than timing, but because of the relationship the audience may have with the music now, as a classical arrangement responded to by Jonny Greenwood. The work ultimately embodies a tone similar to that of the British when the plague broke out, one of commemoration and remembrance. Penderecki named his already existing score after one of the most horrific atrocities committed in the 20th century, and though his arrangements may sound like an immediate sonic reaction to the bomb dropping, it was initially a project sought outside of those parameters, only to be renamed later. However, those piercing violin screeches could not be more appropriate for tackling the incident, and despite Greenwood’s responses being angled towards his appreciation for the composition and for the artist, they still conjure the most grim and glowering visualizations.

While commemoration and remembrance have the potential to bring about feelings of ire, remorse, and sympathy within a macabre framework, there still remains a fragile borderline between documentation and glorification. When a photograph of Nidal Malik Hasan is used as album art, darker territories are crossed, particularly when set among a backdrop of releases that also depict skewed pictures of war and violence. Dominick Fernow’s Vatican Shadow project is pitched as “music for assassins on the world-scale board game,” and although the cover for Kneel Before Religious Icons is not a direct exemplification of macabre imagery, it does call into question issues of taste and heroic virtue. The photographs indicate a dark humor, but carry a confident, provocative weight in an approach that remained consistent through the entirety of Vatican Shadow releases this year; from Iraqi Praetorian Guard to Ghosts of Chechnya to Ornamented Walls, these recordings have encompassed a desire to magnify enthusiasm for the rich, sinister techno Fernow produces through striking emotive aural chords while simultaneously encompassing themes of death and suffering in a pseudo-military context. Such methods capture the imagination in a fashion similar to techniques deployed in tugging on the strings of intrigue that are plucked by the mass media in channeling audience volumes: Whereas (independent) artists might use shocking and provocative visuals to draw attention or sell albums, world news entities employ similar tactics to sell commentary. When covering reports with political thriller twists, these factors are immediately embellished to pull greater statistics, and this is due to a holistic, otherwise untapped fascination for the macabre. These tactics achieve results, and 2012 was awash with tales that were capable of caressing these curiosities like a troubled stockbroker massaging his temples.

The Sacrament of Confirmation

For death to be incorporated effectively as a means of attracting interest, playful embellishment mutates into an essential component, regardless of any secondary objective, such as the by-proxy promotion of a side-project or the proposed restructuring of the Communist Party; much more is brought to the table with the anticipation of murder, corruption, and treachery. When it was uncovered that the British businessman Neil Heywood had in fact been poisoned while staying in Chongqing and that he had suspicious ties with the rising and reputable CCP all-star Bo Xi Lai, an investigation promptly ensued. The story was haphazardly discussed in the Chinese press, which operated as a mouthpiece for the global media who picked up and re-ran the findings of China Daily and CCTV 9. This grizzly ransacking of public image and reputation not only brought about the separation of Mr. Bo and his wife, Gu Kailai, but also saw the latter sentenced to death, while her husband is yet to be seen in public since his arrest. The dramatic nature of this narrative and the suspense it created was incredible when taking into account that the 10-year change around in government was successfully completed without any major disruption to the status quo, while a seeming Maoist resurgent was held behind bars and manhandled for corruption and murder charges.

With execution, murder, and politics, with a hint of lust and a one-party power struggle in the air, it could very well mean that Mr. Bo ends up on the cover of Fernow’s next album — surely he bears all of the credentials, in spite of how impossibly far apart these two stories might be. But that’s just the point: they are probably as relevant to one another as the shooting at Fort Bragg was to Prurient’s Caribbean Overdose before a desire to expose curiosity for the macabre led to an intriguing approach to cover art. What remains of interest is not only how a deliciously productive musician has entwined himself with macabre affiliations and abominable world events through creating his own peculiar little niche genre of techno with a shock junkie aesthetic, but how the passing of major artists can go relatively unreported when the circumstances are not quite as stirring.

Despite the undemocratic nature of the Chinese political system, it still has the potential to encourage full and flagrant responses to injustices exposed, which provide a captivating context for observing innovative dissidents who remain stranded in such political predicament. Josh Feola is responsible for the fascinating 100 Flowers column on TMT, which he recently used to discuss the work of Yan Jun, who has been able to operate as a pioneering sound artist throughout China without patronage, while his contemporary, in-house dissident Ai Wei Wei, took to protest, dancing “Gangnam Style” in a pair of handcuffs, a video that was almost immediately censored in China after being uploaded online in October.

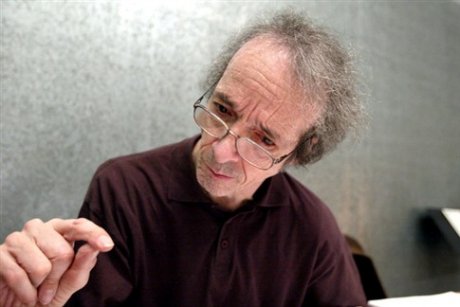

The reaction to such political circumstances ranges dramatically across the board, and while the CCP was gaining momentum in quashing mass revolt all over Tibet in the 1950s, the Estado Novo was wreaking havoc right through the Iberian Peninsula where Emmanuel Nunes was studying at the University of Lisbon. The Portuguese regime made it so difficult for the young musician to continue his studies in classical scoring that he was forced to take private lessons from Communist party member Fernando Lopes-Graça, who eventually persuaded Nunes to move to Paris, where he lived intermittently until his death earlier in 2012. One can not be sure if it was due to an absence of murder and lust that was lacking in the Portuguese composer’s death, but the occurrence went devastatingly unreported in international press. The man was an extraordinary musician and one of the finest avant-garde practitioners of the last century, who successfully crossed the border between electronic investigation and what would now constitute contemporary classical art forms. He passed away in September, leaving behind an stupendous legacy of wonderfully gloomy experimental scores. Never a man to stray from the macabre, one of his most recent pieces embodied a musical interpretation of Dostoyevsky’s A Gentle Creature, the tragic tale of a young girl driven to suicide by her disdainful older lover. Regarding his orchestras, Nunes was always keen to emphasize that “it is more important for me to know what I do not want, than for me to know what I want.” In the case of his later recordings, he proved to be an artist who took little delight in creating cheerful and prissy art, but his avant-garde scores continue to maintain their brilliantly haunting air.

Emmanuel Nunes. Photo: Arquivo Global Imagens

Emmanuel Nunes. Photo: Arquivo Global Imagens

The feel of compositions such as Nachtmusik is distinctly eerie, exposing a tendency for adopting plot lines and inspiration from doleful Russian suicide novels. The macabre angle is a factor the audience experiences atmospherically. Nunes’ breathtaking orchestras and grandeur chamber music create tangible listening environments within their sonic embodiments of the themes explored, and this is an essential component to the darkness that sound alone is capable of conjuring over a plethora of genres. When Nathan Shaffer interviewed Locrian and Mamiffer back in Feburary about their then forthcoming release Bless Them That Curse You, similar points were made during a discussion about song titles and the forlorn themes that run through that extraordinary collaboration. Faith Coloccia of Mamiffer reflected on the sonic representation of ritual and the manner in which states become altered through separation and decomposition, pulling on ideas concerned with tarot readings and divination, influences that could not be more apparent on the album as a whole. Such concepts are aurally transfigured into lengthy, bludgeoning pieces that stir up some wonderfully macabre imagery; sustained bass guitar drones fed through unrelenting hiss and submerged vocals, an inevitable ceremony lament ebbed across six tracks that pertain to an artistic drive for exemplifying an irrepressible gloom. The track titles are indeed indicative of the aesthetic nature of the music; “Second Burial” kindles imagery of that very act, and it is dealt with in a fashion that would generally be considered tasteful and discreet in its tackling of a subject so often deemed taboo — representational of memory, reflection, and commiseration.

Free Exhibition on the Motoyasu River!

The avid presentation of guts-on-screen and the graphic savagery that might be associated with horror genres, grindcore, and death metal has been substituted here to focus on more powerful images. Rampancy and extravagance merely disfigure the occasional inclination one might share in watching a slasher film or listening to Pig Destroyer, credulous hyperlinks for a macabre fix that demand a specific context in order to fully provide any desired affect, and for over 40 years, Kaneto Shindo proved to be inexplicably masterful in assembling conditions that undoubtedly delivered the goods. Although he died in May at the age of 100, this treasured director experienced a life of great misery and tumult, which was brought out in some of his most celebrated works. Perhaps his most renowned film, Children of Hiroshima, returns to events commemorated sonically by Krzysztof Penderecki in his threnody, the damage and struggle of civilians affected by atomic fallout and the livelihoods that were destroyed as a consequence. Shindo’s projects are visually uninhibited through their focusing on disfigurement and incineration, themes that were revisited later on in his horror films of the 1960s, specifically Onibaba, which seizes upon the torment of mutilation in scenes that have been inaccurately described as “otherworldly,” a description often attached to depictions of the macabre, particularly when the subject remains so distant in its abject terror.

Shindo’s productions drew from personal experience as well as survivor accounts from actual occurrences. Each enterprise was thoroughly researched and re-imagined for global audiences, who became susceptible to grim reminders that uncompromising degrees of truth lie in what his audience was subjected to. This lies at the very forefront of what the macabre has always stood for: a documentation of gruesome truths as a means for release, sacrament, commemoration, or remembrance. To think that these themes have continued to exist so pressingly over time is quite astounding, though they are also a constant reminder of the harsh realities that inspire them. Baline Harden published his Escape from Camp 14 earlier this year, a book that saw him working side by side with Shin Dong-hyuk, the only individual known to have been born and then to have escaped from a North Korean gulag. It is without question a harrowing read, one that forgoes any doubts about the cruelty expressed in Shindo’s vision; the deaths that occur in these camps go unseeingly marked by any bout of concession or remembrance that would trigger refracted emotional disappearance or sense of loss, for even the glibbest funeral march has the potential to kindle flames of remorse and revenge that give rise to fires of discontent, protest, and rebellion.

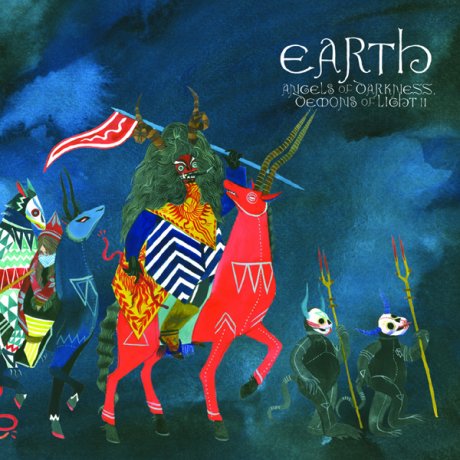

Cover art for Earth’s “Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light II”

Cover art for Earth’s “Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light II”

Regardless of the form it takes, procession and ceremony instigate recollection charged with feeling, a combination destined for collective commiseration that is equally as essential for the battleground. When Stacey Rozich first brought her cutthroat effigies to life for Earth’s Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light I, a victor was framed standing behind the slain, an incarnation of Liu Bei triumphs over a Nian lion, both are depicted equipped for battle — horns sharp, tongues hissing, and paper-chain entrails gushing — a wonderfully striking image that operates as scaffolding for the tumbling gothic rock that pours hence. This year’s follow up features a comparably heroic representation: marching Taotie characters; a smokey, hued twilight; and an entourage of fabulously decked-out miscreants. The album pitches death as an unstoppable force against the sluggish drench of the music it harbors, an unmovable object. A synthetic funeral dirge packaged in its own sedation, a cascading demise of wispy triumph that crystallizes the very essence of the macabre through its surly and beckoning expiry.

In a subjective sense, Angels of Darkness left a disjointed mark on the works compiled by some of the artists who died in 2012 — the husky, dramatic scenes of tribute conjured by Kaneto Shinodo or the strategic reflections of Po and Lovecraft in Škvorecký’s The Engineer of Human Souls. Indeed, Škvorecký’s style was esoteric and gruesome, but it came with such large doses of humor that it was possible to shrug off the mini-tragedies that took place within the worlds he spun throughout his writing. It exemplified macabre as a feedback loop that complemented the author’s struggle in opposition to the daily grind, an exemplification of how the writer used uncanny situations concerning his upbringing to further beautify the efforts of other writers and artists who impose themselves on the characters they create, who in turn have about as much in common with each other as, say, Shin Dong-hyuk does with Jonny Greenwood. As an estranged collection, the handiworks rendered within constitute a depiction of apprehensiveness that remains universal, particularly when taking into account the constantly evolving approaches to communicating personal tragedy, death, and decay. Through various formations and styles, these artifacts typify a fresh body of material within an exhibition that only continues to expropriate and contort, uninterrupted, as another year draws to a close.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series