We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

While the filmic landscape of 2012 A.D. was characterized by apocalypses, our favorite films this year pointed toward a triumph of the real, reveling in our fucked up world instead of imagining its destruction. Directors turned their lenses (usually warped ones) to the immediate and the present — or at the very least, the rippling continued effects of the past (12 Years a Slave). Sure, our list includes some fantastical films — most obviously ones about robots (Pacific Rim and World’s End), but also mind-controlling worms (Upstream Color) and nearly everything else (Wrong, The Rambler). But overwhelmingly, in 2013, shit got real.

More documentaries (a half dozen!) ranked in our favorite 30 than any previous year, with two in our top five (Act of Killing, Leviathan). And whether dismantling documentary veracity in search of personal truths (Stories We Tell), foregoing narrative altogether (Bestiaire, Leviathan), or limiting themselves to found footage (Let the Fire Burn), all the docs (not to mention Everything is Terrible’s found-footage collage double feature) on our list manipulated form in search of new ways to represent our world.

Meanwhile, the dismembered scraps of traditional documentary techniques littered our favorite fictional films, which employed found footage, mockumentary, non-actors, vlogs, and voyeurism to show us such horrors as the wreckage of post-tsunami Japan (Himizu), school shootings (The Dirties), sex tourism (Paradise: Love), economically stagnated suburbs (Pavilion), nerds (Computer Chess), and Florida beach culture (Spring Breakers). Even in the films that fell solidly within the formal confines of fiction, subject matter was immersed in large-scale contemporary concerns (Drug War, Mud, Frances Ha), while the generic conventions of realism were reworked for contemporary audiences (Sun Don’t Shine, Before Midnight).

As always, we had a difficult time narrowing our list down to 30 films: Hors Satan, Pain and Gain, Beyond the Hills, and Escape from Tomorrow all deserve honorable mentions. But this year, our staff had more consensus than ever about the films we loved. Maybe it’s just that we live in a weird time, both IRL and filmically, and our list reflects that. I mean, a release with no press became one of our favorites (Black Box), a Harmony Korine film played in nearly every multiplex, Pacific Rim’s kaiju washed ashore, and, amazingly, we actually laughed at stand-up comedy (Everything is Terrible: Comic Relief Zero).

30. A Touch of Sin

Dir. Jia Zhangke

[Kino Lorber]

The four narratives that combined to form the vividly engrossing A Touch of Sin shared an unhappy view of contemporary China. Jia Zhangke’s vignettes each explored the toll exacted by persistent injustices in his homeland; in one, local corruption so broke a man that only a killing spree could get him to smile; in another, an unemployable romantic’s only achievement was his Foxconn-style suicide. Jia’s filmmaking was hardly as lugubrious as that, however. Flourishes of genre and astonishing images of industrial and otherwise non-urban China kept us immersed as assassins returned home and humiliated mistresses sought refuge. Jia’s indictment refused to remain uncomplicated, with elements of traditional (the Beijing Opera) and contemporary (socializing with an iPad) culture included not so that they might be condemned but because they offered fleeting respite. And yet we couldn’t emerge from the film without retaining a vision of a country made deeply ill by its industrial progress. A Touch of Sin spoke full-throated to the ongoing punishment being meted out on the masses shuttling towards survival employment throughout China, bellowing at a despondent crowd, “Do you understand your sin?” Jia’s ability to wring masterful storytelling from such a toxic situation provided perhaps the most comprehensively moving filmgoing experience of 2013.

29. The Dirties

Dir. Matt Johnson

[XYZ Films]

The world premiere of The Dirties at Slamdance came just weeks after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, and there was a lot of apprehension about how a film that humanized a perpetrator of a school shooting would go over. But at the Q&A after the screening, director/star Matt Johnson fired off rounds of depths-tapping insights about the topic, showing thoughtfulness, passion, and compassion and being unafraid to be hilarious. The Dirties was a fearless and frightening movie that grew out of Johnson’s fascination with the Columbine shootings. The conceptual ambition of the film — to draw a line from high school bullying to a shooting in an organic and believable way — was matched by its nervy execution: Johnson and his crew walked into high schools without permission and mingled with real students, shooting scenes surreptitiously. What started out as a sharp, comedic buddy-movie, relying on Johnson’s brainy film-geek energy and charisma, gradually shifted tone as his character alienated his only friend and descended into a kind of relatable madness. As the zero hour approached, he increasingly spoke right into the camera, and you couldn’t help feeling strangely complicit in his actions.

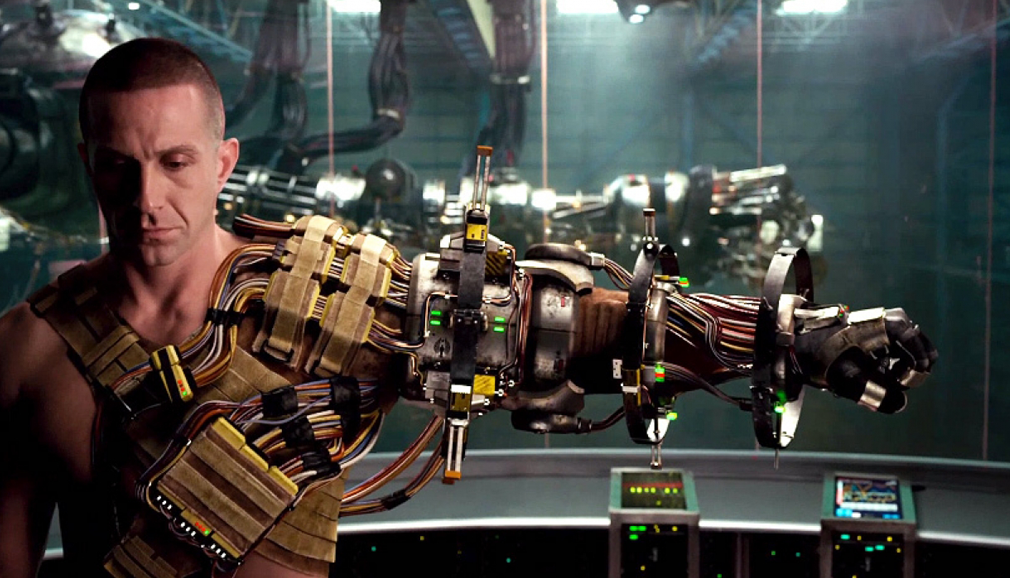

28. Pacific Rim

Dir. Guillermo del Toro

[Legendary Pictures]

I am a liberal arts hack with an appetite I keep cloistered deep in my movie shelf. But no matter how much I banter about Kieslowski or Bergman, no matter how I argue the value of L’Avventura over La Dolce Vita, no matter how strict a diet of documentaries and fringe cinema I consume, an addict-twinge itch asks me: “Why are there no giant fucking robots?” At the pith of my being, I’m still a thirteen year-old Toonami fanboy making models of Gundam Wing robots (yes, it was that bad). Pacific Rim did something flooring: sated my desire to see giant robots live-action fuck shit up. Blockbuster narrative tropes? Don’t care. Static characters? Whatever, Stringer Bell was in the movie. I had no investment whatsoever in any scene featuring an actual human being. The only complaints I had about Pacific Rim were the possibility for more giant robots and the fact Los Angeles wasn’t destroyed. This year, Quentin Dupieux rendered a new vision of French Surrealism. Kim Ki-Duck tore open humanity’s capacity for malice and compassion. Guillermo del Toro had a giant robot cut a monster in two with a sword in the fucking stratosphere. It’s a hard toss for me.

27. Himizu

Dir. Shion Sono

[Gaga Communications]

It wasn’t until a knife-wielding young man jumped onto a stage and interrupted an acoustic set that Himizu really won me over. “Who am I? Tell me please!” the youth yelled as he waved the knife at complete strangers. It’s a question every 14-year-old struggles with, and even as I approach 24, I still don’t have an answer. Himizu detailed the torturous life of 14-year-old Sumida in post-tsunami/meltdown Japan. But Sumida suffered from more than the typical teenage angst and anger (“Ordinary is the best!” he exclaims, a new anthem for emo kids everywhere) that’s to be expected with puberty. Throughout the film director Shion Sono reminded us that life is abusive: a mother deserted her son, a father wished his son was dead, a boy repeatedly abused a young girl who loved him. The ease with which so many of the characters resorted to violence seemed a reactionary response to a new world order in the wake of the tsunami. Some scenes, like when Keiko’s mother revealed a gallows she built for her, were too surreal to be taken literally. But regardless of the reality of these moments, they were representative of an unforgiving, unfair, and unbalanced world — a world Japan entered on March 11, 2011.

26. Room 237

Dir. Rodney Ascher

[Highland Park Classics]

With Errol Morris-like fastidiousness, Rodney Ascher brought forth our first video mixtape inspired and soundtracked by film obsessives. Rather than considering the speakers based on their appearances, the viewer was put in direct play with a constant aural stream of intense reflection, theory, and plum crackpot madness. We were drawn in, made to balk, and often absurdly stuck somewhere in between (like that “impossible window” in Ullman’s office). There were likely some Shining fans who winced as much as they were thrilled to experience a beloved work of art explored in a variety of exhaustive (sometimes exhausting) ways. But Room 237 ultimately emerges as a tribute to an indelible film and to an artist whose meticulous nature fleshed out vivid realms both crude and austere, whose ethereal forms manage to loom larger than the story at hand. Whether or not you bought what was being said, this film took you on a compelling, deliriously unreliable tour through these realms. Throw in that humorous, oddball selfconsciousness (as previously seen in Ascher’s awesome 2010 short The S From Hell) and this film is nothing short of a game changer. Stephen King, Stanley Kubrick, and Rodney Ascher are all responsible for some the most uncannily mesmerizing works we are lucky to have to get lost in. Thankfully, Ascher is only beginning to show us what he can do.

25. Viola

Dir. Matías Piñeiro

[Cinema Guild]

As we watch an all-female cast play, and replay, a certain scene from Twelfth Night (don’t worry if you missed a few lines), one can sense the contact high of the language’s courtly slipstream, but also the proud eyes behind those words rolling off the tongue, and the hungrier eyes receiving them. The affected appraisals of Shakespeare’s dialogue soon drift into a backstage debate on modern relationships, where, upon inviting us to ogle his insanely attractive cast, director Matias Piñeiro switches to vernacular: should one enter a state of mental separation from a lover, loving less; or do you go “all in”? Likewise, you can decide whether to try and decipher Piñeiro’s narrative sleight-of-hand, as the fluidly roving camera and direct sound constantly suggest more than the loosely defined network of relationships on screen; or whether to simply enjoy its many sensual and intellectual pleasures. Weirdly specific and unceasingly warm, Viola’s evasive structure invariably suggests intrigue, but honestly, the first time I watched it, it felt like someone finally made the crossover product for lovers of gossip columns, Romantic literature, and Karagarga. The second time I realized there was no better film this year about allurement — the allure of language, cinema, and of human beings.

24. Gravity

Dir. Alfonso Cuarón

[Warner Bros.]

As someone who’s basically afraid of anything cold, expansive, or improperly lit, Gravity was my worst nightmare. This free-spinning visual gargantuan followed an insanely on-point marketing campaign, punctuated memorably by Sandra Bullock’s panicked gasps as she hurtled helplessly into the void. Director Alfonso Cuarón turned an estimated $100 million budget into an overwhelming mise-en-scène of splintering space debris and rapid day-night shifts across the looming face of Earth, all shot with astounding detail. As Dr. Ryan “I Hate Space” Stone, Bullock gave surreal, barely conceivable moments an agonizing familiarity, and provided a canvas for 3-D technology to intimately connect with weightless surroundings — when Stone finally cries, the tears lift off her skin and float towards the camera (speaking of: whoa.) Gravity’s relatively simple screenplay also helped highlight the obscure origins of the survival instinct: does it stem from a sense of obligation? A selfish impulse? For our part, is the spectacular hubris of movie-making all it takes to convince us to strap in for 91 minutes of pure emotional torture? Whatever the implications (and Neil deGrasse Tyson’s protestations aside), Cuarón’s magnum opus of ocular gluttony and body-punishing stress breathed visceral life into the movie-going experience.

23. Mud

Dir. Jeff Nichols

[Lionsgate]

To borrow an expression from a colleague here in Portland, Oregon (Matt Singer of Willamette Week), we are in the midst of a McConnaissance: the abrupt and welcome shift in the career trajectory of one Matthew McConaughey that has found the 44-year-old actor taking roles that are challenging, sometimes daring, and worthy of his remarkable abilities. For all the flash and physical changes that he brought to other films, his work in Mud is really the crown jewel of this fantastic run McConaughey has been on. It’s a simple enough part — a fugitive waiting on a small island for his chance to connect with a former flame and escape — but he imbues it with the perfect shades of mystery and danger and his incredible charisma. You understand completely why the two boys that find him on the island keep returning to him with food and supplies to help in his flight. McConaughey is aided here by masterful writer/director Jeff Nichols, a filmmaker who understands the delicious allure of doing potentially unsafe things when you’re young. His clear-eyed vision does a great job of capturing both the thrills and the horrible consequences of these actions in this brilliant bildungsroman.

22. The Rambler

Dir. Calvin Reeder

[Anchor Bay Films]

In the opening scenes of The Rambler a man has just been released from prison: blue jeans, hat, sunglasses, red filter cigarettes, background country music. But make no mistake, these clear pinpoint references will soon be lost in the barrage of bat-shit insanity that follows. That is not to say The Rambler loses its place. If it’s true that art must communicate something to the audience, the path chosen by Calvin Reeder is a strange and difficult one — to quote FBI special agent Dale Cooper from Twin Peaks. The rapid speed at which the film flows made us feel as if we were switching channels in a demonically possessed TV set: surreal mise-en-scène, late night exploitation cinema, crazy scientists and their inventions, roadside shows, nightmarish horror, mummies, exploding heads. Gratuitous gore. And a girl (there has to be a girl) with whom our hero finds brief moments of peace. The line between uncompromised personal view and self-indulgence is very thin, and it’s no surprise The Rambler divided audience and critics alike. Calvin Reeder is one of the most promising contemporary American filmmakers currently pushing the boundaries of challenging, experimental cinema.

21. Post Tenebras Lux

Dir. Carlos Reygadas

[Strand Releasing]

Carlos Reygadas’s meditation on family, fear, and desire didn’t so much contain a narrative as it collected images. Post Tenebras Lux explored moments in which memory and dream became indistinct, and in doing so permitted us to acknowledge that we possess such a multitude of bodies and fears during our lives, and that to discuss them as a single unbroken continuum is frankly dishonest. Whether offering us a small child wandering alone after dark in a field far from home, or a woman having her first group sex experience in a crowded bathhouse, or a man so ridden with guilt that he yanks his own head off, Reygadas announced that he’s ready to celebrate a world as unsettling as ours. A deeply autobiographical film, Post Tenebras Lux dismissed actorliness in favor of regular human mundaneness, a choice that permitted Reygadas to linger on the organic choices of his actors. The rewards were manifold, and the film populated itself with images of unalloyed comfort and brutality. The Mexico Reygadas’s characters inhabited, complicated by class yet seemingly beyond civilization, offered natural beauty and human cruelty in equal measure. With Post Tenebras Lux, the director wrought an unflinching fantasy that explored the contours of desire and traced an unseemly world we can’t help but inhabit.

20. Black Box

Dir. Stephen Cone

[Cone Arts]

Undoubtedly our biggest cinematic surprise in 2013, Stephen Cone’s Black Box came out of nowhere (a void, a black box, no press, no hype) but has hauntingly occupied our lives since. Black Box was a film about a theater production of a novel, but what propelled it were stunning shifts in tone — not the shifts between narrative levels for which such multi-textual material would seem ripe. Instead of flaunting high-concept meta à la Charlie Kaufman, Black Box framed adaptation as a normal human (rather than an exceptional textual) activity. Even in its numerous and electrifying scenes of actors playing actors, nothing seemed doubly performed: for these theater majors, like all of us, playing roles and playing selves were part of the same messy continuum. Their off-stage acting out of their own desires and hang-ups collided weirdly yet elegantly with the play’s fictional source material, a macabre young adult novel that allegorizes society’s brutal policing of youthful bodies. But Cone didn’t make a message movie. For all the clarity of the interactions between characters within the small, unadorned space they rehearsed in, what ultimately lingered was opaqueness: of their lives beyond the space of performances (mere glimpses), of the production they ultimately perform (only moments), of the book it’s based on (snippets). Cone made a film that was firmly in the immediate, yet pervaded by ghosts.

19. Pavilion

Dir. Tim Sutton

[Factory 25]

A year or so ago, I was invited to stay at a young friend’s house for awhile. The night I arrived, he was getting a tattoo in the living room. His friends were sitting around, getting stoned and drinking shitty domestics. Their home was going to be foreclosed upon. They had given up even trying to take care of it. Grass had turned back to dirt. The garage door didn’t close all the way, and no longer concealed the trash piled up, waist high. The night before I moved out, my friend stumbled into my room drunk, looked down, and mumbled, “I’m sorry.” Sometimes when I think about who art (often) leaves out, I think about people like him. Let’s be honest. There is no poetry in undeveloped suburbs. There is no poetry in being stuck in a dead end, minimum wage job. There is no poetry in letting your ambition slip into oblivion. It’s fucking shitty, and sad, and desperate. And while there was so much in Pavilion worth celebrating, above all is the way it took its camera into the one place that would never appreciate its gorgeous product, and let it rest.

18. Sun Don’t Shine

Dir. Amy Seimetz

[Factory 25]

In spite of the title, the sun was almost omnipresent in Sun Don’t Shine, Amy Seimetz’s impressive feature directorial debut (she’s already an indie household name with her acting career, including an outstanding performance in Upstream Color, also present in our year-end list). Taking the classic noir staple of two lovers on the run but placing the characters against the backdrop of sunny Florida, the reasons behind their fleeing is just was mysterious as their personal backgrounds. We did know, however, that something was very wrong. The sun-drenched imagery was in sharp contrast to the claustrophobic close-up shots, which reinforced the somberness of their clashing personalities, paranoia, and personal anguishes. Road movies often touch on themes of self-discovery and freedom, intertwining the two amidst the promise that the highway will take us someplace new. Everything will be forgotten. But at the end of the day, we find ourselves burdened by the weight of our personal traumas no matter how far or how fast we go. We learned very little about these two people, but we could deduce from the very first scene, in which Crystal (Kate Lyn Sheil) desperately gasps for air, that their fate was doomed. And the sun won’t shine.

17. Paradise: Love

Dir. Ulrich Seidl

[Strand Releasing]

Unsurprisingly, John Waters said it best: “Fassbinder died, so God gave us Ulrich Seidl.” It’s not hard to see what Baltimore’s resident shock comedy filmmaker/artistic genius loved in the first part of Seidl’s Paradise Trilogy — it’s at once the most upsetting film in the filmmaker’s deeply upsetting oeuvre and the first to truly embrace a comedy of the absurd, even if that comedy was of the cold and formally rigorous Austrian variety. In a year rife with raw looks at the intersection of race, sex, and class in a fully globalized context, Paradise: Love’s extremely explicit look at female sex tourists and Kenyan lovers was the most schematically calculated of the bunch, and commendably so. But it was the knife’s edge intermingling of comedic kitsch and horror, Renaissance beauty and modernist severity, that set it apart and brought its rigorous dissections into increasingly murky territory. Aided immeasurably by Margarethe Tiesel and Peter Kazungu’s nuanced and warm performances of exploitation embodied, no other film this year wandered as far into the deep end of desire as Paradise: Love did in its climatic half-orgy of tinny boomboxes and ribbons tied onto flaccid cocks. Funny, though.

16. The World’s End

Dir. Edgar Wright

[Focus Features]

In five years, fans of Edgar Wright will likely find it hard to imagine his Cornetto Trilogy without this year’s concluding entry, The World’s End. But for now, it just sort of rests there. It’s good, but is it as good as the other two? Was it sci-fi enough? Was it funny enough? All these built-in pressures and inevitable comparisons surely weighed on the director, as he funneled one of his most elaborate, layered stories through some of the sharpest, most frenetic reaches of his now-signature visual style, into an end product that still feels firmly rooted in the current comedic landscape. There was another apocalypse comedy this year. There were other meditations on arrested development. There were other movies about beer or aliens or groups of friends getting back together etc. But who cares? Wright worked his ass off on this movie, and for all the merits of uniqueness, it doesn’t trump skillful, intelligent execution, which this film has in spades. Add to that the unmistakably present voice of a talented director, and it’s tough to argue that The World’s End isn’t a worthy finale.

15. Wrong

Dir. Quentin Dupieux

[Drafthouse Films]

Wrong showed the lighter side of existential dread. The film’s increasingly befuddled protagonist tried to find his lost dog in an absurd world where duplicitous gardeners were struggling to learn how to draw, it was constantly raining inside an office, and dogshit had its own story to tell. If done poorly, this would be the stuff of nightmares — or worse yet, pretentious student films — but luckily, writer/director Quentin Dupieux handled everything with a comic bent that highlighted his assured filmmaking and firm grasp of tone. William Fichtner delivered one of the best performances of the year as Master Cheng, the enigmatic guru who loves animals, invasive telepathy, and maintaining an exquisitely groomed rattail. There was a sense of menace and creeping doom lingering under every scene, giving Wrong an enthralling, dangerous feeling that anything could have happened — and it would all still work. Wrong will live eternally in the poorly lit gloom of the insomniac’s room, a new cult rising for an utterly unique film with profound moments gleaned from a funhouse-mirror reflection of our lives.

14. Everything is Terrible! Does the Hip-Hop / Comic Relief Zero

Dir. Everything is Terrible!

[Everything is Terrible!]

While the first two Everything is Terrible! films are both great, it wasn’t until Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochiez!, their first film with a decided concept, that their work transcended to a state of pure found footage, ADHD bliss. Relying on much broader (and easier to navigate) concepts, this double feature follow-up re-formatted the cultural detritus of hip-hop and stand-up comedy. Everything is Terrible! Does the Hip-Hop Vol. 1: Gettin’ a Bad Rap! is as much pregame/power hour dance party as cultural critique. Courtesy of the editing skillz of the Final Cut “pros” at EiT!, the film contained the propulsive rhythm of a music video. So hypnotic was this effect it made us here at TMT dance along as they turned VHS vomit into Jodorowsky gold. If Gettin’ a Bad Rap was the party, then Comic Relief Zero was the come down, a sobering look at comedy routines that are just that: routine. By decontextualizing and recontextualizing stand-up performances, ugly patterns emerged: racism, sexism, homophobia, bad comedy, to name a few. A stagnant, unforgiving portrait of stand-up coalesced, forcing us to re-examine ourselves and our tastes. With this new double feature, EiT! has made us face our demons — for exploiting an art form and for exploiting each other.

13. Stories We Tell

Dir. Sarah Polley

[Roadside Attractions]

A documentary in the sense that it is non-fiction, but purely a film in that it dwells far outside the factual and clearly within the subjective, Sarah Polley’s third feature, Stories We Tell is a hyper-egoistic document of her own life and family, told through recollections of Polley’s mother from near everyone who knew her. It plays less like reading someone’s diary and more like reading someone’s medical charts; it’s personal and purposefully intrusive on the lives of Polley and everyone else involved, similar to Jonathan Caouette’s absent-mindedly brilliant Tarnation in that Polley and Caouette are both fascinated with themselves, their own stories, and deem them worthy of greater examination and exposure. The narrative of Stories We Tell is both marginally important and incomplete, told not just from one perspective but from many. And that distinction — that this story (or stories) exists in so many forms at once — is as much the point as the “story” itself about Polley’s mother, her husband, and another man in the 1970s. It is about the story and about the action of telling the story, at once and equally, making something greater than just entertainment: a conversation.

12. Pieta

Dir. Ki-duk Kim

[Drafthouse Films]

Gang-Do, the central character of Ki-Duk Kim’s Pieta, was animalistic and he is not animalistic. He committed acts of violence (mercifully left off-screen) like a predator stalking his prey, chilly calm exploding into blood-letting terror. He committed acts of sex (mercilessly left on-screen) like a stray, both pathetic and utilitarian. Elementally, though, these traits are not natural to only the animal world: humans, too, can have all warmth chipped away into numb, unfeeling survival. It was only through the appearance of his mother, Mi-Son, a woman who abandoned him at birth, that he was dragged into the world of human emotion. As Pieta’s events unfolded, the audience was left developing pathos for the previously-irredeemable Gang-Do, while witnessing the horror of vulnerability — a complete spectrum flip from the cruelty of the film’s outset. South Korean film has developed a reputation for innovation in the field of revenge, but Pieta suggested the most brutal tactic of all may be forcing a person to feel. Oh, to be a dog again.

11. 12 Years a Slave

Dir. Steve McQueen

[Fox Searchlight]

Once, maybe twice a year, I see a film that makes it difficult to talk afterward. 12 Years a Slave was that film for me this year. Eyes damp, my friend and I shuffled out into the cold street sighing, staring fixedly, and shaking our heads. Despite some unconvincing accents and producer Brad Pitt’s cameo, the film’s representations of life (or half-life, or life-in-death) as a slave, slave driver, master, master’s wife, and so forth were viscerally and intellectually shattering. The only adequate words I have are Kafka’s: “Altogether, I think we ought to [watch] only [films] that bite and sting us. If the [film] we are [watching] doesn’t shake us awake like a blow to the skull, why bother [watching] it in the first place? So that it can make us happy, as you put it? Good God, we’d be just as happy if we had no [films] at all […]. What we need are [films] that hit us like a most painful misfortune, like the death of someone we loved more than we love ourselves, that make us feel as though we had been banished to the woods, far from any human presence, like suicide. A [film] must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.”

10. Bestiaire

Dir. Denis Côté

[Metafilms]

The popular bestiary, or compendium of beasts, of the Middle Ages depicted, aside from the known science of the animals contained therein, moral lessons that reflected the belief that our world was actually the word of God made tangible. It’s a fitting title for Bestiaire, the Québécois documentary that gave us an unnervingly dispassionate view of, primarily, dead animals and animals behind bars. Unlike its medieval forebear, the film made no explicit commentary about the morality or immorality of the wild animal park or the taxidermy workshop on view, but the conclusions we were given agency to draw for ourselves were likely about our relationship to the natural world and any higher meaning that relationship might reveal. Zebras frantically tearing around their after-hours enclosure in a flurry of furiously dancing hooves (one of the most deeply terrifying moments on screen this year); a monkey with the sorrow of the ages in its eyes devotedly dragging an oversized teddy bear around its enclosure; an enormous exotic bird stretching its one remaining wing to a staggering width in a dark, narrow room: these images by themselves spoke volumes about the darkness of our place among God’s creatures, in relation to history and as they stand alone in the modern age, if you were willing to read them.

09. Let The Fire Burn

Dir. Jason Osder

[Zeitgeist Films]

If you cornered me at a holiday party and asked about my “favorite” movies of the year, I probably led with this one in the hopes that it will get the audience it deserves. Jason Osder’s all-archival documentary is a tough sell, and sounds medicinal when you try to describe it. The film details a racially-charged event from 1985, when a Philadelphia police raid on the compound of a black separatist group spiraled out of control. The botched raid ended in a city-sanctioned firebombing that killed 11 of the group’s members and burned dozens of houses to the ground. There’s power in the story itself, and in the themes of racism, civil disobedience, and violence it evokes, but the experience of reliving the story worked on me in unexpected and deeply moving ways. On a formal level Let The Fire Burn is an accomplishment of precise, clinical editing, but under the icy precision of the storytelling there’s a raw core of emotion. It’s a layered visual feedback loop, a warning that quotes Faulkner in newsreel footage and video depositions: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

08. Drug War

Dir. Johnnie To

[Variance]

Although it’s hard to pin down a director who has made over 50 films ranging from hyper-violent Hong Kong action flicks to bubbly romantic comedies, 2013 saw Johnnie To return to the form of his superb Election series with the release of Drug War. Set in mainland China, To’s film examined the parallel bureaucracies of the criminal underworld and state police force, and, in so doing, offered up a unique take on how crime operates in contemporary Chinese society. On the surface, Drug War appeared to adopt the black-and-white morality of classic gangster cinema: the dogged, stoic g-man embodied by Captain Zhang Lei (Honglei Sun) purposefully contrasted with bombastic characters like the laughing sociopath Bro Haha (Hao Ping) and the Machiavellian Tian Ming (Louis Koo). This dichotomy worked its way into the style of the film itself, transforming procedural realism into tragic opera. Contrary to many observations, the violence of To’s action films wasn’t so much toned down for this effort as it was bottled up until the climax. While To’s film maintained its outward binary morality, the finale’s brutally literal destruction of both the criminal and police apparatus hinted that the two sides of the titular “war” exist in dark symbiosis.

07. Before Midnight

Dir. Richard Linklater

[Sony Pictures Classics]

Most movie romances end with “happily ever after” or something similar. Before Midnight was the most romantic film of the year because it abandoned easy endings: sure, Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) were beloved characters after the other two Before films, but director Richard Linklater actually dared to consider how romance can exist after years of marriage, with a couple of kids along the way. His strategy was the same as before. The literate script was co-written by Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke, and it gave Jesse and Celine ample time to converse and argue. There was a constant push/pull of power in their relationship, now deepened since there was genuine emotional baggage instead of romantic folly. We followed them on holiday in Greece, culminating with a night in a posh hotel, and the movie was brave enough to consider how a couple still manages to preserve their sexual chemistry. The final argument between Jesse and Celine was as seething as anything from the previous two films, and because it ended with a quiet moment of empathy and grace, there was little doubt they were soul mates. The love in Before Midnight wasn’t happily ever after; day after day, it’s doggedly until tomorrow.

06. Upstream Color

Dir. Shane Carruth

[ERBP Film]

We waited nearly a decade for Upstream Color, Shane Carruth’s follow up to the metaphysical mind-bender Primer. Undeniably unique and utterly transfixing, his second effort was a hallucinogenic trip that connected the dots between parasites and psychosis, all while deftly expressing the dysfunction and symbiosis of codependent love. As challenging and demanding as its narrative was, it had a surprisingly simple logic: the worm-pig-orchid cycle. Alien and strange, certainly, but it cohered. It made us want to follow its disorienting path and try to keep up. We were drawn to its prismatic majesty as it overwhelmed our senses. Even when we didn’t know what it all meant, there was an understanding of two devastated people, a kinship with them. They were damaged, beautiful and so confused. Oh yes, the film was spectacular to look at, but the real pleasure was searching for what was hidden. Questions begat questions and our readings were our own. Carruth was kind enough to give us some closure as an antidote to the Lynchian aftertaste: as dialogue disappeared near the end, we were left with the language of nature and the thrill of vengeance. When it was over, many of us were ready to dive in again, and so we did.

05. Frances Ha

Dir. Noah Baumbach

[IFC FIlms]

Frances Ha felt like a big step forward — or at least a fresh start — for writer-director Noah Baumbach. Fortunately, this was all the while still retaining the restless intelligence, hyperarticulate characters, and barbed wit we’ve come to know and love from him for nearly two decades. Perhaps it was the film’s miraculously unaffected homage to the French New Wave, with its crisp black-and-white cinematography and charming Georges Delerue-scored montages, that helped balance Baumbach’s typically-caustic sensibility. More likely, however, was the distinctive influence of co-writer and lead actress Greta Gerwig, whose blitheful disposition and whimsical nature masked an undercurrent of unease and sorrow. Her lived-in performance as Frances, someone whose poor judgment and bitter luck keeps her perpetually out of step with the world around her, was simultaneously knowing and soulful. Although “heart” isn’t a term I’d normally apply to Baumbach’s work (and nor would I want to), Frances’s speech about “having your person” was one of the most unexpectedly moving scenes of the year. Some people said that the world didn’t need another chronicle of a struggling urban twentysomething artistic-type. While that may be true, Frances Ha was so funny and perceptive that it felt fresh and alive all the same.

04. Leviathan

Dir. Lucien Castaing-Taylor & Verena Paravel

[Cinema Guild]

Something akin to an episode of The Deadliest Catch as directed by Stan Brakhage, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel’s mesmerizing and intensely visceral Leviathan captured the brutal realities of life at sea in a dizzying, kaleidoscopic montage of perspectives. Shot with an array of tiny cameras attached to wires, chains, nets, and the fishermen themselves on a commercial fishing boat off the New Bedford coast, Leviathan was as close to a purely sensorial experience as cinema achieved in 2013, plunging the viewer into the ocean before thrusting them upwards into the sky to soar amidst the seagulls and cutting to every imaginable position on and inside the ship until the film became a beautiful yet terrifying abstract ballet of motion and stasis, blending the mundanity of the shipworkers’ routines with the implacable fury and violence of nature that surrounds them. Leviathan is not so much a traditional documentary as a synthesis of imagistic and sonic fragments that together form a complex system representative of the holistic relationship between man and nature; not one of symbiosis, but rather dominance and force in the face of a deep-seeded fear of the unknown and unknowable. As the ever-quotable Werner Herzog has said, “the common character of the universe is not harmony, but hostility, chaos, and murder.” Leviathan most assuredly agreed as the sheer savagery on-screen, as normalized and mundane as it has become to the fishermen, was a powerful reminder of what mankind has done and continues to do to survive, or at least to eat fish.

03. The Act of Killing

Dir. Joshua Oppenheimer

[Drafthouse Films]

Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing was the kind of film that made you wish you didn’t have eyeballs. Impossible to unsee and yet completely necessary to watch, it was an unfailingly outrageous reconfiguration of performative truth. The film dissected itself, weaving segmented blocks of narrative into a thread beyond categorization, beyond living and rationality, leading us into the blank space of what comes after murder, after the witnessing of death. Oppenheimer turned his camera over to the death squad (“gangsters”) responsible for killing and raping countless alleged Communists during the overthrow of the Indonesian government in 1965 and asked them to recreate the killings. It wasn’t even so much the matters of brutality as it was the flickers of instants wedged in between — “‘I look like I’m dressed for a picnic,” Anwar Congo said as he watched a playback of himself demonstrating how to strangle someone with wire, “I never would have worn white.” There was no moment not pinned with dread, the relentless sense of something seething in the undercurrent of what makes us human. It was a bigger anger than anything I’ve ever seen and the kind of film you’ll take with you to the grave.

02. Computer Chess

Dir. Andrew Bujalski

[Kino Lorber]

With Computer Chess, Andrew Bujalski applied the lo-fi, semi-improvisatory methods of his earlier films to his most ambitious project to date: a serious comedy depicting a convention of computer chess programmers in the early 1980s. The film found teams from universities and private ventures descending upon a nondescript hotel to test their programs against each other in rounds of tense one-on-one competition. The characters revealed just as much about themselves and their work during the off-hours — in all-night bull sessions, misadventures with stray cats and lost room reservations, and run-ins with a new-age encounter group sharing hotel space. With his mostly unknown cast fully inhabiting their roles, Bujalski layered each scene with off-kilter humor, psychological depth, and resonant observations about the implications of technology in American society. His much-heralded use of analog video equipment served as a means to an end, like the film’s meticulous period details — haircuts, clothes, cars, and especially computer equipment — which were never used as a punchline or for diorama-like preciousness. Bujalski situated artificial intelligence within its historical context, foreshadowing its future while examining how, as the last vestiges of the counterculture gave way to the Reagan Era, technophilia surpassed spirituality as a reigning American obsession.

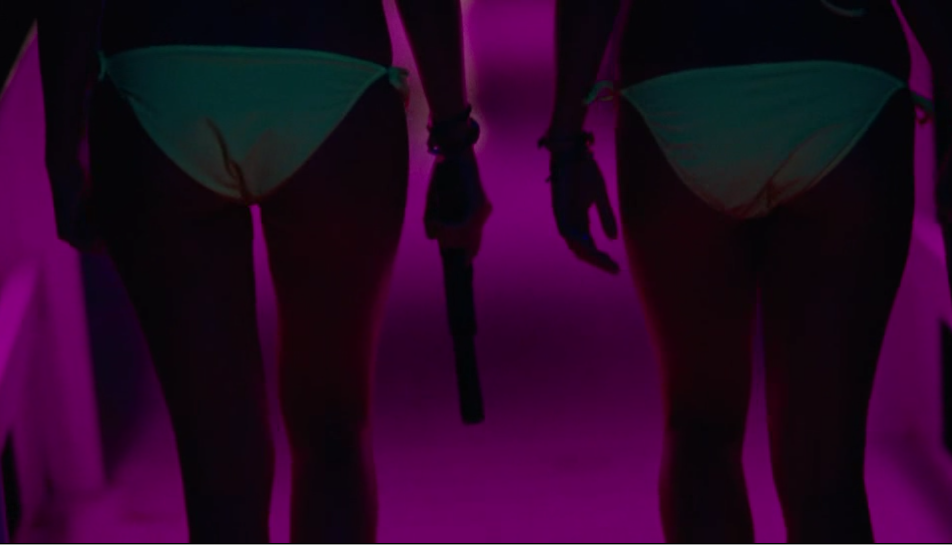

01. Spring Breakers

Dir. Harmony Korine

[A24]

I don’t think any of us were really expecting to be as blown away by Harmony Korine’s latest film as we were when it opened. The press for Spring Breakers suggested pretty bluntly that it was definitely going to be bonkers enough to merit a viewing or two. But the concept felt a bit too obvious, even for Korine, who’s long since eschewed anything remotely approaching guile in his filmmaking. The early trailers were a kaleidoscope of James Franco all coked up and ridiculous trying to pull off a convincing Riff Raff impersonation, a whole bunch of raunchy hand-held footage of debauched teens on the beach, and some Disney/ABC Family starlets going buckwild with guns in bikinis and pants with lettering on their butts. It just seemed like such a bald-faced cash-grab. I mean, don’t get us wrong, we were sure we’d enjoy every minute of it. We just didn’t think it was going to be so damn great.

Korine wrought some of the most chilling and daring performances from a cast that — let’s face it — hasn’t really been doing their utmost to earn either of those adjectives in recent years. We were delighted when it became so obvious that Alien was the role James Franco was born to play, and no amount of Faulkner butchery is ever going to take that away from him/us. Ashley Benson, Vanessa Hudgens, Selena Gomez, and Korine’s own wife, Rachel, knocked it out of the park in ways we never thought possible, playing such ostensibly empty characters with a devastating gravity. The legwork required on Korine’s part to get those party shots which seesawed so jarringly between hypnotically beautiful and raw as hell was impressive enough in its own right, even before we stopped to admire just what it was he was accomplishing with all this exquisite trash.

If there’s one unifying thread that runs through the remarkably disparate gross of films that made our list this year, its a willingness to boldly experiment with staid forms of storytelling, and we could think of no better work that encapsulates this tinkering than this one, with its virtually straight noir storyline, that still manages to unsettle as much as any of the zanier work of his young days.

Spring Breakers was exactly the kind of eerily meditative, high NRG freskshit scattergash the world needed when it arrived this spring. If 2013 has branded itself the Year of Offensive Content™, then Korine’s latest was the harbinger of that label, touching on all the themes that would later consume so much of our time arguing about on the internet. Korine has spent the better part of his career trying to convince us that his movies are more concerned with the beauty (and, yeah, it’s often grotesque beauty) of what he’s throwing up on the screen than on the perceived or actual meaning of what’s underpinning them. If this hasn’t closed the door on that particular debate for you then nothing will.

We loved this movie unironically. We loved it because it was a cash-grab and it didn’t give a rip about being a cash-grab. We loved it because it shared a speed-freak continuity with the greatest of Terence Mallick’s visual work. We loved it — and we still do — because it was the best thing that happened in film this year, and there’s no one else in the world who could’ve pulled it off. In the end, this film was a great equalizer, a singular creation that bridged the insurmountable gap between auteurist vision and candy-colored materialist excess. Spring Break forever, bitches.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series