We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

6

Szczcepanik’s album, then, engages with the problem of not knowing in quite a subtle and complex way. Because even when we do know, even when we do “get” the reference, as it were, that reference turns out to be about the problem of knowledge itself. A complete knowledge of the work always turns out to be just out of reach, just beyond the horizon.

Here we have a perfect encapsulation of the problem music critics confront every time they approach a piece of music: the demand, or even the responsibility, to know a work, even in the face of the ultimate imperfectability of that knowledge.

Vladimir Jankélévitch

Vladimir Jankélévitch

This is what the philosopher of music Vladimir Jankélévitch called the problem of the “ineffable.” Crucially for Jankélévitch, music is ineffable not because it is somehow meaningless or because the listener’s relationship with it can only ever be radically personal. Music’s ineffability does not reduce the responsibility to attempt to know a work; it increases it. For Jankélévitch, music is bewildering; it can often seem to resist description or critical knowledge not because it expresses nothing, “but because it does not express this or that privileged landscape,” because “there are infinite and interminable things to be said of it,” not zero.

In other words — and this is the crucial point — for Jankélévitch, music’s ineffability is not a reason to stop trying to know and explain it. It is only in the “imagining and dismissing, and doing it again, and again” of a piece of music’s meaning, power, and import that “one asymptotically approaches an intimation of something that will elude any and all searchlights.’

7

The type of critical (un)knowing we are advocating doesn’t come quickly, or easily. We don’t want to suggest that it’s always possible and should be expressed in every single piece of music criticism. Only a few of us can find — and even fewer of us can afford — the time required for this kind of critical work.

However, we do think that the nemesis of this critical work — the logic of refusal that we outlined at the start of this piece — makes it all the more difficult to achieve. In fact, we think it’s both symptomatic and productive of a kind of reduced listening. And this reduced listening — to put it bluntly — fits all too neatly with the kind of subject imagined and brought into being by the ideological and technical assemblage of contemporary hyper-capitalist individualism.

If we look at the major purveyors of online music criticism today — websites like Pitchfork, FACT, Dummy, Resident Advisor, and of course our own Tiny Mix Tapes — it is clear that we are caught up in a tight feedback loop, in which content is made possible by advertising, which in turn demands a specific type of content. These platforms are therefore increasingly beholden to the demands of the daily — and, in many cases, hourly — news cycle, which privileges quick, and preferably first, coverage of new albums and singles, upcoming tours, and exclusive releases. The ideal listener in this context is of course an isolated consumer, one who imbibes content quickly and moves on. And a critical logic that rejects structure or history in favor of a purely sentimental response suits this ideal listener perfectly.

To be clear, the kind of criticism we’re describing is certainly not unique to this new era of digital information. It extends back through the days of Melody Maker, Cream, NME, and Rolling Stone into the classical tradition and beyond. Throughout history, music has often been talked about as if it were the quintessentially “expressive” art form, peculiarly resistant, therefore, to anything but a personal response. Today’s new media infrastructure has intensified this tendency, but it has also, on an optimistic note, made it more obvious, and so perhaps easier to identify and combat.

Here we have a perfect encapsulation of the problem music critics confront every time they approach a piece of music: the demand, or even the responsibility, to know a work, even in the face of the ultimate imperfectability of that knowledge.

8

Having spent most of this piece focusing on a relatively obscure entry in this year’s roster of new music, we’d like to conclude with brief comments on a phenomenon that has for many (either for good or for bad) been the hallmark of 2014. We’re talking about the clutch of artists associated with A. G. Cook’s PC Music label.

The label’s artists and their friends (like SOPHIE, Felicita, et al.) have clogged this year’s airwaves with a new brand of shiny, sugary dance music, which takes shape in the cloying teenage-sincerity of Danny L. Harle’s and Hannah Diamond’s love songs, in the choppy pop collages of GFOTY, and in the euphoric synth materialism of SOPHIE.

This music (and the polarized responses to it) have already prompted a good deal of critical reflection. Those who like it — like Philip Sherburne (on Pitchfork) or Clive Martin (on Vice) — have recognized that what makes PC Music interesting is that, whether you like it or hate it, the reasons for doing so are obvious, right there on the surface.

Promotional image of QT holding the QT Energy Elixir

Promotional image of QT holding the QT Energy Elixir

The label certainly wears its heart on its sleeve. According to an interview with Tank Magazine, Cook named it PC Music because it’s for music that’s, well, made with computers. And if Cook’s own music sounds a lot like cheesy overproduced pop songs, that’s because he really likes cheesy overproduced pop songs. The tunes own up fully to their syrupy, high-energy sweetness: SOPHIE’s most recent tracks are called “Lemonade” and (in collaboration with Cook as producers for “QT’) “Hey QT,” which doubles as an advertisement for a fantastical new energy drink, “QT Energy Elixir.”

Unlike other hyper-pop acts we’ve discussed previously (like Yen Tech), there’s not quite the same smirk of art-world irony here. Although the PC Musicians do have their high-art reference points, their approach seems far more pragmatic. Cook admits that he and his friends are simply trying to recreate, at an individual, amateur level, the role of major label music labels and producers — a task focused as much on questions of image as music. The implications of this are ambiguous:

What interests me about pop music and commercial imagery in the first place is that it has the potential to be overwhelming, extravagant and banal all at the same time. Not only that, but mixing “high culture” with pop culture has lost its radical edge to the extent that it’s more or less mainstream. Challenging something’s commercial nature is a commercial tactic in itself, and authenticity is a tricky currency that is often swayed by branding and advertising. I have nothing against this, and many people respond to this kind of stuff in a sophisticated way. Though it means that there is room for a subtler and possibly more compelling way of engaging with these ideas, where shock value and direct irony is replaced with ambiguity and uncanniness. My work’s constant use of instantly gratifying elements such as kitsch imagery, catchy hooks, synthetic colours and fun sound effects feels inevitable, it’s almost a compulsion rather than a choice.

PC Music is corporate pop reduced to, in Cook’s words, a “style of craftsmanship,” not as a form of ironic appropriation, but as an expression of, as Adam Harper has recognized, the ambiguity of “desire.”

PC Music can be, and often is, vindicated or decried on purely subjective terms: you either love the songs’ exciting new dance sound, or you find it chintzy and over-the-top. The music seems to encourage this sort of response. Yet for all its upfrontness and superficiality, PC Music also (and very deliberately) leaves the desiring listener with a series of unanswered questions.

9

How are critics answering these questions?

In a recent review from The Wire, writer Louis Pattison attempted to answer at least one. He suggested that the PC Music phenomenon, and its links to publications like LOGO, which he accurately notes “blur the lines between journalism, fashion and advertising,” eschews an alarming politics. As Pattison says, PC Music may be “the first homegrown London dance music in memory to smack of whiteness and privilege: neoliberalism twirling a glowstick.” Of course, this is exactly the label’s provocation. Its advancement on previous movements like vaporwave is its ability to make precisely these sorts of complicities explicit. Pattison’s review answers back to this provocation: and this, in our mind, is exactly what criticism should do.

PC Music is, in the end, the shiny, seductive, other side to Szczepanik’s slow, obscure, orchestral movements. Szczepanik’s Not Knowing, we are arguing, explicitly anticipates or invites an “unknowing” listener, one whose position can be assumed in more or less critical ways: either as the listener who refuses to know or the listener who engages in a process of knowing, in which unknowing remains a crucial horizon.

In a similar way, PC Music also opens onto an ambiguous politics of listenership. The question is whether the listener engages with this politics critically or simply reflects it right back.

1. Elgar, quoted in Charles Richard Santa and Matthew Santa, “Solving Elgar’s Enigma,” Current Musicology, No. 89, Spring 2010.

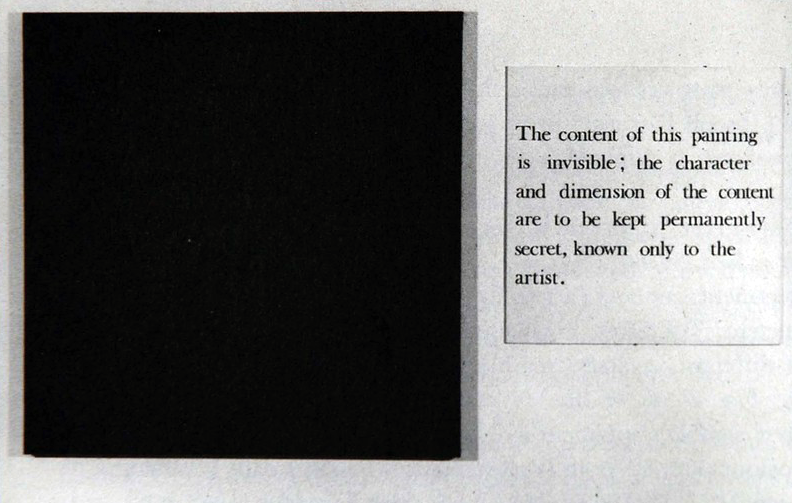

[Header Image: Art & Language (Mel Ramsden), Secret painting, 1967-8]

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series