Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films and TV shows that kept us staring at screens. More from this series

“The new bible will be an eternal magnetic tape of a time that will have to reread itself constantly, just to know it existed.”

– Chris Marker, Sans Soleil

Introduction: Your Feature Re-Presentation

Coming soon: We fetishize our memory, counting out time in representations of what used to animate our psychic lives. We worship static images and guard ourselves against the diminishing returns of reiterative pleasures. Tirelessly, Hollywood indulges us, streamlines what once unfolded like an endless universe of play into a series of series, a cascade of formally conservative masculinist continuity exercises in exposition and suspended disbelief. These blockbusters tend to center their plots on male characters, fetishized militaristic action, and heteronormative romantic conventions, a standard responsible for the corporate-feminist surge of female reboots/recasts and the prominence of marketing blockbusters that “stand for equality.” It serves a fantasy, whether we need (and deserve) a vision more revolutionary. When the studios realized they could count on nostalgia to fund properties that are often too big to fail, they made it (im)personal.

And these reboots better feel personal, right? I have no desire to stack the stacks of printer paper covered in Blue Squadron dogfights buried somewhere in my parents’ basement against the endless more stacks of blue faces lining the Disney vault. I’m sure I had as much fun, fell as deeply in love with the new hope of The Force Awakens as you did. The enormously successful soft-reboot of the Star Wars saga (a trilogy of trilogies that in their entirety I was always already ready to believe in) is the real occasion for my anxiety about market-researched franchising, about the exploitation of our embarrassingly rewarding thrall to continuity. I spent however many hours pacing the halls of Cloud City, podracing through the rock arches of Tatooine, clashing lightsabers as Plo Koon, and now hugging Poe. And still, after my first viewing, so many of the soft-reboot’s symptoms metastasized across my memory of The Force Awakens.

The soft-reboot: Hollywood’s answer to fatigue from remakes and sequels. It pretends to be novelty in a world without fatigue, rather than singing to the mysteries of fatigue itself. It masks with measured appeals to cult sensibility and the promise of a bigger and better and forever future for the franchise. Old casts would foster fresh faces, old signs would be interpolated in shocking codes, old cues would signal new beginnings, old narratives would structure bolder stories, old universes would be explained over and against or elaborated into new canon. The formula is designed for maximum fulfillment of consumerist desire: we want the old new again and forever, as we always would. But my incorruptible, unconditional love of Star Wars was supposed to transcend that sort of conditioned and conditioning studio work, to capture me without using industrial tractor beams; it’s so near to my heart, so enmeshing.

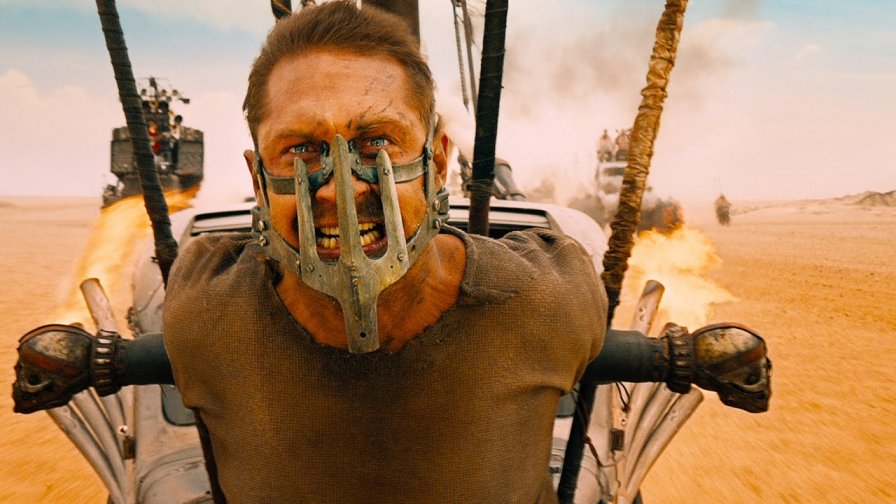

One of the more memorable recent movies that so enmeshed me in its storytelling and sensuality was 2014’s Thou Was Mild & Lovely, which in its creeping lucidity only grew more feverishly disorienting and mesmerizing. Maybe an experimental “art film” (somehow also a coagulating genre) is an unfair or irrelevant reference for Hollywood’s biggest event pictures. But Mad Max: Fury Road, the next movie in my viewing life to come closest to that fevered fixation, is definitely a tentpole to be measured against and showcases an actually revolutionary ethics, not just a corporatized appeal to equality. Of course, for its singular madness, it will become itself a reboot model, and the industry standards will autocorrect in their way, likely without the radicalism.

That doesn’t have to read like defeat: Because there’s ample space for sensitive repetition and insurrection within this decade’s soft-reboot revolution, minor revelations at the marginal interstices of major productions. Because there’s a lot of love in this retelling of Star Wars for its millennial, captive audience. Because it’s so hard to read against the molecular monopoly of the Disney sandcastle, its series’ entries as granular as solvent particles, its totalitarian form(s) as monadic as a chain operation and an indivisible source. If this is all for the fans, what have the studios shown us we want? What is the work of art in the age of mediated reproduction?

In 2015, we watched self-aware blockbusters pander to their built-in bases with allusionary plots and exploit/employ identity politics for an imagined progressive audience. We watched some of the most striking visuals and soundtracks of mass cultural consciousness repeat themselves firmly enough to stir up something like marvels. And flickering in the sandstorm noise of the expanding blockbuster summer, there were screenshots that provided the barest relief from auto-pilot origin stories, that might even re-envision a cinematic “present present” for political and formal radicalism in a Hollywood mainstream obsessed with aesthetic pleasure of the first order.

But that’s not the first order. That’s the resistance.

The First Order

A brief history of franchises in 2010s reboots (some softer than others) on the silver screen: X-Men was given a prequel reboot that crossed over with its original franchise to retcon itself from the future for a coming recast. Star Trek was rebooted in an alternate continuity as explained by time-traveling Original Series Spock to then remake an original sequel. Rocky made a comeback as Mickey for a new franchise. The Fantastic Four got younger. Spider-Man was rebooted with new origins, only to be rebooted again in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) in 2016. The Ghostbusters will be a new (and all-female) set of SNL alums. Mad Max took a backseat to the furious fixation of a new protagonist. A new generation of Griswolds went on vacation to Wally World. Star Wars forced the old cast onto its new crew. Superman was rebooted from a reboot to battle a Batman rebooted from a reboot. Judge Dredd went slo-mo, Godzilla got bigger, The Planet of the Apes rose again, and Jurassic Park was re-opened for big, big business. Whew.

Hollywood would have us believe that this content circle unfolds in a straight line of progressive (technical, if not creative) achievement, like Ultron 2.0 ripping its originary self in half to proclaim how much bigger and better a vision it can dream up. And it works (toward profit/meaning)! The industry didn’t just turn cannibal in the past decade, but the insistent and successful redeployment of established franchises reached new heights in 2015. Michael B. Jordan alone starred in two reboots: the Oscar-nominated (though he was snubbed himself) Rocky revamp Creed and the sabotaged Fox flop Fantastic Four. The year’s top earners were record-breaking reboots Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Jurassic World. The eternal return on investment of well-established properties ensured that this history, as it has been since studio cinema’s industrial beginnings, is neverending.

Every property recalls itself, on our behalf, but something has changed for the Information Age. This decade’s reboots reproduce an uncanny cinema experience, subjecting us to movies that not only know what they are, but know that we know what they are, as an apology for convention. Postmodernism as the affective grounds for blockbusters, an acknowledgement of the mediated memories of audiences that asks us to detach ourselves from expectations at the same time it appeals to our sentimental attachment to the original. Its calculated cynicism washes the sensation from the screen. These films don’t actually upset the industry standard reboot formula, origin story, or hero’s arc (The LEGO Movie mocked it before couching its anti-capitalist, anti-blockbuster bent for normative family values), playing without plying a new relationship to film out of it, as if that battle were over. Metalepsis as a rhetorical, and especially ontological, device has a destabilizing transparency and performative quality, but the affective zone suspended or trespassed in these softly rebooted blockbusters tends toward a representation petrified, not mutative. Jurassic World is the most narratively exploitative and flagrant user of this self-awareness, structuring itself as a rigidly conservative balk at metalepsis. The impersonal inter-zoning of 2015’s premier dinosaur thrill ride is a monument to the corporate-pitched, self-aware intelligent design of Hollywood reboots.

One of our protagonists, Aunt Claire, is introduced giving a corporate pitch that might as well be describing the high concept pitched to Universal Studios, suggesting that audiences demand something bigger, never seen before, and (as the returning Dr. Henry Wu later says) cooler. Claire references the surge of information gathered from genetic research compared to archaeological digs, establishing a dichotomy between the reboot-design CGI of Jurassic World against the practical effects and handmade storycrafting of Jurassic Park. In the control room, Jake Johnson’s non-character later refers to how much cooler that Park was for its “authentic dinosaurs” and decries corporate sponsorship while wearing actual Jurassic Park/Jurassic Park apparel in a movie with a closeup of Beats headphones in its opening shots.

Jurassic World is seen through a child’s eyes, with competently common shot selection and sizing, as an attraction (the spectacle of the park) within an attraction (the spectacle of the film) within an attraction (the audience’s attachment to Jurassic Park). The child’s eye perspective evacuates a history with the Park, makes our subjects seem especially vulnerable to the plot’s dangers, and lowers the expectations for nuanced dialogue (though it shouldn’t). They’re vacant characters, pure witnesses to the action, emotional signposts like the crowd-characters in the Godzilla reboot or the onlookers on the doomed Republic capital in The Force Awakens. These witnesses are without contemplation, and so we pass by looking on without looking in.

The designed attraction for the new park and representative for the movie itself is the Indominus rex, the antagonist whose every feature and action is explained moments after we watch it. As the triumphant Jurassic Park theme swells, the spirit of the original movie is designed to come alive in the reboot as the superherofied T. rex teams up with velociraptors to overcome its unworthy, extra-artificial successor, the Indominus. That climactic dinosaur struggle isn’t the only third-act anxiety about the wholesomeness of Jurassic World compared to its original. Near the film’s end, the roughly inserted InGen military works to establish a new continuity by setting up conflicts for future sequels at the same time as it represents an outside force that would exploit the (un)natural beauty of the dinosaurs (like Universal coming in to inhumanely resurrect the franchise).

Director Colin Trevorow’s one visual motif is a closeup of feet landing with an ominous thud, revealed to be harmless (a raven’s claw in the snow of the central family’s front yard, a baby triceratops’s hoof in a petting zoo, maybe even Claire’s heels). It’s a sign of the movie’s own suspended suspense, where the tension is limited by the predictable attachments to the original movie (in winking references that remove you from the action or in rehashed plot beats that act like an affective GPS). Every time the chaos theory of a million moving parts starts to vibrate too wildly, studio hands ensure the rippling water in the cup on the dash doesn’t make a mess, that everything stays within the calculus of park logistics.

Fan Service in the Winking Wasteland

Every music cue, every reimagined scene or dialogue callback, every pin-light to our franchised memory projects impossibilities over the movie world. The cinematic universe becomes a closed conversation of established continuities and canons, a map of stars with no interest in the dark matter that influences it all from within and without. It’s an information overload, a supersaturation of the imagic screen solution that crystalizes its liquid content into a lower energy state. And it’s winking at us.

The Force Awakens is steeped in a fever pitch of fan service, from Han’s and Rey’s reference to the Kessel Run to stowing away on the Millennium Falcon, the ten-times-bigger Death Star (I know, Starkiller Base) to the resolutely 1970s aesthetic. I didn’t even realize how badly I wanted to watch one of our heroes fly a TIE fighter or Han borrow Chewie’s bowcaster. The moments that stood out most were the few that seemed of their own movie and not indebted to fan service, like Rey’s lonely life on Jakku sliding down sand dunes and preparing meals for herself. In that familiar rush of callbacks and character moments, there’s more than a touch of that metaleptic soft-reboot storytelling (the search for Luke’s legendary Force sensitivity is a MacGuffin for J.J. Abrams as much as the characters). While auto-piloting through Abrams’s pseudo-remake of A New Hope, did no one else miss the messy and unprecedented plotting of the prequels? George Lucas’s vision seemed to operate out of order with Hollywood; those movies hardly gave us anything we already knew we wanted.

I imagine, for some, it’s blasphemous even to consider Episode VII a reboot in what was a saga that, for itself, always demanded (more) resolution. More unnerving to me is the delusion of choice that has conditioned fans into a dispassionate consumer criticality. This vigilance is most notorious for geek properties, which have the disciplined fanbases of a cult. They will defend a studio’s decision-making on a brand level, integrating an industrial and historical understanding of the property into their fandom. It’s an apology from viewers on behalf of the creatives for, say, the over-familiar plot structure of The Force Awakens, because everyone knows Disney had to regain the trust of Star Wars fans after the prequels. If there’s one thing Disney knows how to do best, it’s serving it up.

There’s a passive-aggressive sleight of hand in the studios’ fan service, with its increasingly telegraphed gestures toward controlling images from our childhood canon; it’s meant to suspend our attachments and prolong our fandom ad infinitum. There were so many appeals to cult memory this past year: When Age of Ultron comes to a screeching halt so Hulk can battle the new Iron Man suit wearing the newest Iron Man suit. Rocky coaching Adonis till he catches the chicken and running up the famous steps. That trip back to the Jurassic Park compound, replete with restarted Jeep and the subsequent raptor/T. Rex/mosasaurus tag-team victory.

All these winks add up to what? A detached, pleased experience at the movies and a deadened sensitivity to the works that don’t blink an eye. These movies rely on and therefore reify the past-present as a pure and petrified model to represent, thus implicating themselves as stale and predictable in their representativity. The most distracting moments in The Force Awakens are those that recall A New Hope structurally or as recollection, straining for novelty by clinging to familiarity. A more vivid vision for reboots admits the clouded contemporaneity of representation, steers for the horizon before doubling back on itself, collapsing everything that oversaw but didn’t believe.

Revolutionary Road: The Resistance

“Power is everywhere therefore nowhere, diffuse rather than pervasively hegemonic. ‘Constructed’ seems to mean influenced by, directed, channeled, as a highway constructs traffic patterns. Not: Why cars? Who’s driving? Where’s everybody going? What makes mobility matter? Who owns a car? Are all these accidents not very accidental?”

– Catharine MacKinnon, Toward A Feminist Theory of the State

The culture industry is meticulously attentive to “the soft center of what adapts,” and 2015 witnessed reboots of classic properties that were also classically white, male, and straight that would at least now feature some non-white stars and some casts that weren’t so male. The reboot is supposed to dissolve the time between experiencing the film you loved and the film you’ll love, to collapse our spectatorship with our attachment to the originals, but it can’t disguise its release in a (hopefully) less homogenized mass media atmosphere without negotiating contemporary audiences’ expectations of diversity. Even if 2015’s mildly more diverse casts were empty studio gestures, it does not undo the power of destabilizing the assumed makeup of almost every Hollywood blockbuster. There’s deep representative force in a Star Wars movie with leads who are black and female.

This imperial march of progress seems the most likely to succeed, with the established success of reboots and franchises carrying whatever perceived risk the studios are willing to take in casting (probably pitched as marketing to new demographics). Still, as so many major vehicles do, these more broadly representative blockbusters resorted in their action to the normative Hollywood ethics, a dehumanizing militaristic impulse (see: Star Wars overlooking Finn’s interiority after attacking and killing the now-humanized stormtroopers). Is there room for revolutionary politics in the retread praxis of reboots? Can we imagine a blockbuster whose representation doesn’t just meet a quota, but blazes with a transportative, transformative ethics? Can we believe in the barest potential for resistance within the irresistable?

George Miller’s return to the Wasteland is a new hope for reboots (radical formally and politically). It’s an improbable antidote for the humdrum wasteland of automatic 2010s masculinist blockbusters, down to the branding of vital resources (Aqua-Cola). What’s more, the movie doesn’t seem designed as a neoliberal feminist vehicle; it’s after something way more crazed. Its conception and execution are absurdly satisfying to witness, given the troves of summerfare that never even consider — and definitely don’t champion — the contemplation of women (as warriors, as guardians, as revelatory/opaque figures/subjects). The anti-patriarchal politics are elevated by an affective register of sincerity, which edges the camp rather than the metaleptic, to sensitize us to this bizarre and all-too-imaginable perverted dystopia.

This means we get grandiose, epic depictions of gross anxieties and power dynamics without the conservative impulse (hey, MCU et al.) to self-reference and indulge continuity. Miller brought a reckless auteurship to Hollywood, serving his original vision by not serving us a representation of how we would imagine it at present. No bows to expectation, no fan service (Max’s most daringly individual achievement happens off-screen). There’s no detached (de)sensibility in the setpiece design or plotting, only a sincere attachment to the brokedown character of Max and the drive of Furiosa, a committed visual language to keep their journey moving. He made the most forward-looking action film in years by refusing to postmodernize his sticky drama, by keeping the momentum always hurtling forward. Fury Road doesn’t take the franchise’s history as its conditions, but works with the material conditions of this moment, which then serves its actual audience, not the base that the studios think for. Through this, Miller paves a revolutionary road.

Opposed to the decadent industrial metagenre (the superherofied and streamlined reboot), Fury Road relies on immersive, visual, anti-expositional storytelling to craft characters and settings that resonate as meaningful without feeling overdetermined. From the first, when Charlize Theron’s Furiosa receives equal billing with Tom Hardy’s Max, Fury Road keeps its central politics in order. I think more than having a “strong female lead,” which is an unremarkable and at this point “correct” decision on a corporate/marketing level, Fury Road features a hero who is strong, determined, feminine, and the embodiment of the film’s (pretty Second Wave) ethics and action. Splendid’s pregnant stomach shielding her protector, milk to wash away blood, Furiosa’s engine-grease warpaint-eyeshadow, the milking mothers unleashing the torrent from the Citadel upon Joe’s demise.

In the first major setpiece, we’re watching Furiosa think, her darting eyes shadowed and scanning for threats. Our hero’s first act of defiance is merely a redirection, a detour that reroutes the entire flow of traffic in that stretch of the Wasteland and eventually U-turns on what was supposed to be a one-way street. She drives the movie’s momentum forward, unflinchingly, out of the firestorm of Joe’s Citadel into her fantastic vision of the Green Place. Furiosa is never objectified for the male gaze; her dialogue is focused on her mission (not romance); and her pain is allowed to show on its own, for herself, screaming at the sun. Furiosa’s imagination and courage and refusal to be dominated fuel the Wives ideologically and affectively, along with the refrain, “You cannot own a human being.” Although the Wives’ already sparse dialogue is cryptic and/or heightened, nested in their banter between is the standout line, “Not a necessary kill!” which immediately distinguishes the Wives’ vision for peace, antithetical to the merciless power they were raised under (and opposed to the remorseless killing of most Hollywood action).

The characters are allowed to interact and care for each other outside the compulsory heterosexual matrix. Max and Furiosa are a defiant Thelma & Louise-styled team born out of necessity, taking the wheel from each other as required, carrying the other when they’re endangered. The closest thing we get to romance is the relationship between Nux and Capable, whose interactions (barring the kiss on the cheek that didn’t read erotic anyway) are decidedly caregiving. With her assured vision of a better future, she quiets his war-poisoned masculine martyr consciousness, saves him from meaningless self-destruction. Not once is dialogue wasted on the mechanizations of conventional love (or exposition, for that matter), which helps reveal a world where romance has become a superfluous system of control, naturally. The Citadel is already in Joe’s hands, thanks to his aquamonopoly. The only coupling required is to meet his tyrannical reproductive futurity. His highness is undone gradually as women’s bodies and his “property” within them begin to fight back and assume power.

Our revolutionary heroines combat a pregnant nation-body of white maleness, that, thanks to a visceral representation of abstract masculinity just as piercing and nuanced as the film’s manifold-feminist depiction of women, draws us closer to the warped world of Max. This bizarre future is not nearly as unimaginable as it might be (we recognize the power structures, the deadly repetitions of want and war). The immediacy of the viewer’s experience with the fallout in part hinges on the movie’s eerie projection of (male) power’s anachronistic/undying mechanizations onto a heightened post-apocalyptic landscape. With its pulp subversion of the classically (post-9/11) terrorist villain and superpatriarchal perversion of fatherhood, Fury Road undoes so much of the unreal realism of this decade’s blockbusters. Miller portrays an institutionalized terror that feels much more familiar, entrenched, and therefore menacing than the renegade individual (Furious 7, Age Of Ultron). Here, the heroes seek revenge/redemption over and against The Powers That Be, unraveling the repetitive, forceful action of That Be. It’s not a self-referential play with the studio creation of the movie, it’s a wholesale disavowal of established processes.

The movie also relishes in the petty family squabble of its three ruling brothers, featuring some of the most absurd, disturbing relationships since Texas Chainsaw Massacre (which also, not unintentionally I think, had an all-male family). The People-eater from Gas Town is the bookkeeper, rendering capitalist desire a cannibalistic fetish so consuming he’s eaten himself into immobility. The Bullet-farmer from the Bullet Farm declares himself a judge, blinded and holding machine guns for scales, firing aimlessly with no regard for the Wives he’s supposed to be protecting. And Immortan Joe is the everyman father refigured as godking warlord, your average Joe elevated to an absurd pinnacle of toxic masculinity. The closeup of his son Rictus Erectus applying his belt, where the skull sigil is seating over Joe’s groin, is a campily decadent sign of the society’s fetishistic worship of male power.

That deification of Joe is the key to his power and overthrow, because once his mortality is proven, the oppressed of the Citadel have no reason to worship. Despite the War Boys’ fanaticism, they too recognize how they were controlled and that they have the ability to change the way things are (just as Nux was able to rework his shame and self-loathing into courage). The movie portrays the ethics of precarity as a revolutionary ethics that does not grieve the overthrown, but revalues and champions the oppressed, while refusing to propagandize individualism — as the music swells, Max drifts away as he always does. When Joe’s body is presented, the entire population of the Citadel participates in the revolution. The War Boys lift the elevator to raise the Vuvalini up, the masses gather and are raised by the Wives onto the platform. The victory isn’t just personal redemption for Furiosa and the Wives and Max or fan service to the stock images of the series; it’s the uplift of the people, a sensual belief in sensation itself, which is a rare, special vision for a Hollywood reboot.

Reloaded v. Revolutions

So we will be as we were, in 2015, captive and captivated in a boxing ring and raptor pen, stranded awake on an alien desert or strapped to the hood of a car, hurtling into a firestorm. The industrial media fixation with nostalgia extends beyond film; television is in the middle of its own network boom of returning franchises (X-Files, Twin Peaks, Full House), and the record industry, reporting its best sales since before the popularization of the CD, sold more catalogue albums than new releases for the first time in history. We are in the midst of a locked-groove freefall through timelessly released classics, every becoming moment becoming more momentous for its anticipation and reception of renewed “original” properties. What a time.

Every artist and studio exec faces Neo’s choice, a choice that we the audience have a misguided hope of influencing: to reboot with the same program that has worked under the existing system of control, or to do something with the potential for the insurrectionary. A train coming into the station, a nightmarish montage of meshy compossibility for storytelling in the mainstream. To wonder at a microscopic cinematic universe that contains more than advertising for the post-credits galaxies within. Maybe Marvel will finally 3D-print a heart to get caught in my throat while I watch a character death we already knew would happen thanks to the performer’s highly publicized contract negotiations.

Reboots are inevitable as they are digestible. Fan service isn’t the death of imagination or the stagnation of cinema. But still: Try shuddering instead of nodding when you read an online comment that applauds the “risk taking” of the MCU for going trippier in Phase Three with Inhumans and Doctor Strange. Try crying at the music cues in a 2016 summer’s reboot of choice (I will be afraid of no ghost, laugh at no degraded phantom). Try sitting in the dark with a bunch of self-alienated strangers failing to make sense out of the story onscreen, one that you’ve never even heard of before. Try forgetting everything you knew about the Expanded Universe and the predecessor trilogies, and just look up at the stars. Can we still believe that the Force surrounds us? I’m sick of applause signs and ready for something that claps back.

More about: 2015

Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films and TV shows that kept us staring at screens. More from this series