We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series

“Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.”

– F.T. Marinetti, “The Futurist Manifesto”

“And in addition, there was no way out. The interlocking between the defective instrument and the defective subject produced another perfect Chinese finger-trap. Caught in his own maze, like Daedalus, who built the labyrinth for King Minos of Crete and then fell into it and couldn’t get out. Presumably Daedalus is still there, and so are we… There is no route out of the maze. The maze shifts as you move through it, because it is alive.”

– Philip K. Dick, VALIS

Introduction: Computer World

Where are we going? In the endless rush to predict the future, it’s easy to forget that we are shaping it. But regardless of the actual path the world is following, we tend to associate the future with electronic music. Since the technology became available, the futures we saw all seemed to require electronic soundtracks. Our aliens, our robots, our hoverboards all sound like synthesizers. Early electronic acts like Kraftwerk directly confronted the relationship between their music and technology, ultimately suggesting that they had fused with the very machines they used to synthesize their vision of the future.

In 2015’s musical landscape, a stream of music seemed to flow from the future, utilizing digital technologies like granular synthesis, processor-intensive DAW plugins, and musical programming languages such as MaxMSP to construct new images of the future through the lens of the present. This year, Arca’s bracing Mutant and Lotic’s intense Agitations shocked us with violent evocations of trauma, while Oneohtrix Point Never’s Garden of Delete and Holly Herndon’s Platform coolly critiqued our immersion in the techno-capitalist landscape. NON Records emerged with a series of sonic assaults on globalist power structures, and M.E.S.H. and Amnesia Scanner released works of deeply-realized sci-fi otherness.

In the endless rush to predict the future, it’s easy to forget that we are shaping it.

In their manipulation of digital synthesis, each of these works (and a number of others, from this year and beyond) suggested a new reading of human relationships with technology and a new approach to the possibilities available to our species. Extrapolating from these works yields a set of techniques and values that, taken together, mark the arrival of a new conceptualization of futurist music. This neofuturist aesthetic, in its manipulation of time, space, and the subject against a backdrop of technological innovation and domination, posits new approaches to the future contrary to those of past avant-gardes and current technocratic and transhumanist philosophies. Against the status quo of progress and alienation, these artists explore new worlds and, in the process, begin to reorient and transform the shape of this one.

Back to the Future: Futurism Past and Present

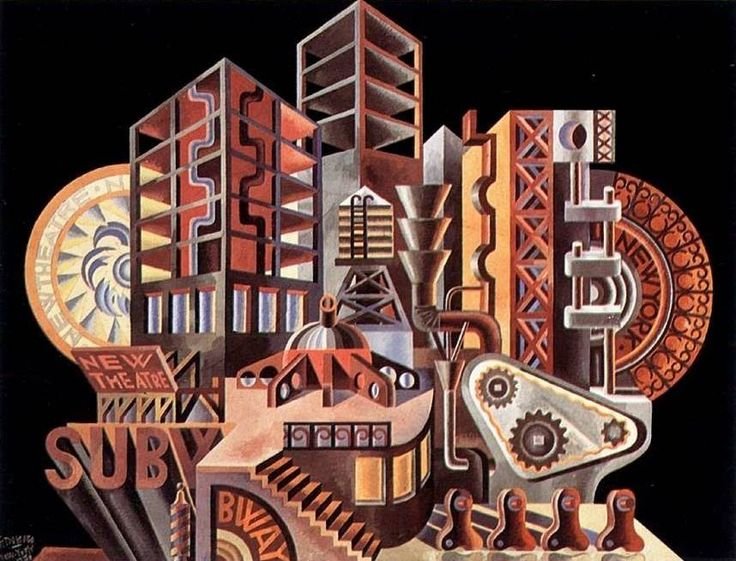

The link between electronic music and what is known as futurism has existed since the inception of the term and outlived the avant-garde movement that invented it. In music, futurism begins perhaps with Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo’s pioneering manifesto “The Art of Noises,” seminal for its influence on 20th-century composition, its position in the roots of electronic music, and its genesis of the idea that noise can be music (an idea that John Cage would push past the Futurists’ slim ideological boundaries). Russolo called for a fusion of the dissonant tonalities of the late-romantic and early-modernist composers with the immense variety of timbres that issued from the machines of industry and war.

But the Futurists were not interested in mere mimesis of machine sounds: “We want to attune and regulate this tremendous variety of noises harmonically and rhythmically. […] Although it is characteristic of noise to recall us brutally to real life, the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction. It will achieve its most emotive power in the acoustic enjoyment, in its own right, that the artist’s inspiration will extract from combined noises.” Keep in mind, however, that the Futurists’ fascist tendencies, explicit misogyny, and program of glorifying war and technology constitute a basis for that enjoyment; see “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” by F. T. Marinetti: “We will glorify war — the world’s only hygiene — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.” Although the Futurists wanted to free art from the shackles of academia and the museum, their anticipated future aligned all too well with Mussolini’s vision of strength, masculinity, and centralized authority.

Since then, another sense of futurism has developed. Futurism might now apply to all that is anticipatory and forward-looking in art, philosophy, technology, and other disciplines. Many groups can lay claim on this basic methodology: New Age spiritualists, conspiracy theorists, and, most prominently, transhumanist technocrats and singularity Kool-Aid drinkers, who believe that the exponential growth of technology will result in a magnificent transcendence of human limitations (including even mortality, for some), which will eventually culminate in the rise of hyper-advanced artificial intelligence, triggering a new, post-human stage in history. Although the New Age has obvious, direct ties to music, it’s important to note that the transhumanists have links too; much ado surrounded the tech industry’s attendance and capital-based privilege at this year’s Burning Man, where EDM reigns over a vast pseudo-TAZ. It’s not surprising that the tech industry looks to EDM for its soundtrack; they expect a slow-burning but exponential acceleration toward the all-encompassing bass-drop of the singularity, when artificial intelligence will outpace human technology and explode in the birth of a godlike supersentience. Along the way, lots of money will accumulate in the pockets of those who best promote that acceleration.

The neofuturist aesthetic critiques the futures that these movements offer while preserving its own anticipatory orientation. Neither utopian nor fully dystopian, works in this mode project a complex future contrary to the Futurist and transhumanist ideal, where the human subject places itself in tension with technological progress, seeking liberation in the spaces between the cracks of the monolith of capitalism. The neofuturist aesthetic is not a unified artistic movement; some artists working within this mode collaborate while others work in total independence. The futures that each artist offers differ, sometimes greatly. However, they all make use of a pool of technologies, techniques, and values that, when combined, fuse the structures of technocratic futurism with their antitheses. Beyond mere critique or cynicism, this synthesis allows these artists to posit a counterfuture of resistance, and beyond it a faint glimmer on the horizon: hope.

The Explosive Event: Temporal Rupture and the State of Emergency

Perhaps the most dominant element in Futurism’s aesthetic program is its apotheosis of speed. Speed represented the acceleration of human potential and the violent desire for progress. That desire is also present in the transhumanists, who see technical progress as an inevitable, exponential continuity building toward the realization of the technological utopia. Neofuturism attacks these myths of temporal development and introduces structures that deepen the complexity of their temporal arrangements. By representing acceleration and then arresting it, by inserting ruptures and breaks into seemingly ideal continuities, by inducing an explosive and explicit state of emergency counter to the suspended and indefinite emergency of the hegemonic structure, the neofuturist aesthetic disrupts the aesthetic paradigms of its predecessors and posits a new organizing temporal motif for its program: the event.

Music moves. It must. Electronic music often moves along a fixed path set by the sequencer, the autocratic clock that organizes all of its notes. This phenomenon is perhaps most important in club music, where synchronized rhythms define the motions of bodies in space. But even the earliest examples of dance music include brief disruptions in that flow, just enough to play with the audience’s expectations or to set up an inevitable return of the beat. The bass-drop in EDM is but one example of this mode; subtler methods, as employed in works like Container’s excellent LP from this year, feature brief cutouts and skips that create anticipation in their sudden arrest of the track’s motion — but the motion forward typically continues shortly afterwards. By contrast, the neofuturist works from this year exhibit a sense of motion and arrest that is often built directly into the rhythmic structure of the track. Moments of arrest receive a sonic weight that is equal to that of the motion forward. In this way, stillness checks the acceleration of speed, complicating the symbol of forward progress with images of crisis.

This effect might be most apparent in the opening phrases of M.E.S.H.’s 2015 release Piteous Gate. Plodding stabs of bass walk forward, broken by immense silences. Their lurching pace evokes the character of a lumbering space-hulk, prevented from moving faster due to its massiveness, slowed in its speed by the sheer immensity of the space it attempts to traverse. By employing silence (and the software that echoes into it), “Piteous Gate” defines the musical space as a cold and void expanse, ready to receive any motion and dissipate all energy. Silence is vast, much more vast than the technical apparatus that claims hegemony. The silence of nature, much derided by the Italian Futurists, is an empty, violent sea, and all endeavors to cross over into it, however swiftly the marches run, are completed only at its behest. M.E.S.H. focuses this technique on “Methy Imbiß,” which features accelerating bursts of drum patterns ending in abrupt stoppage. These drums feature an almost acoustic quality, as if struck by human hands unable to sustain the exponential increases in speed forced upon the tempo. They fall silent before they continue, resting before laboring again at the accelerating machine. Here, the arresting element is not the vastness of space, but the sputtering of the technical apparatus itself. Although technology may serve some liberating function, it also exhausts its operators. The future it offers requires obedience to its organizing directive: efficiency at any cost.

The neofuturist aesthetic disrupts the aesthetic paradigms of its predecessors and posits a new organizing temporal motif for its program: the event.

The neofuturist aesthetic’s motif of the event relies on interruption. Silence slices the wall of sound into fragments, revealing each moment of sounding as a choice, each of which can operate independently in the runtime of the track, shifting the weight of signifying from the forward progress of the song to the individual moment that is occurring. Motion still continues, inexorably forward, as all time is bound, but any particular event in the continuum now receives its own specific mass. This is nowhere more apparent than in the title track of Arca’s Mutant (though “Sinner” and other tracks from the album feature similar structures). Similarly to “Piteous Gate,” sound-masses explode between abrupt silences, but here, any given arrival of sound yields its own variety of elements: shredded vocal samples, huge bass vibrations, rising tones sputtering out into nothing, delaying drum hits, bell tones — any category outlined in Russolo’s “Art of Noises” is available at Arca’s touch. The track’s structure reorganizes itself around each mass, undermining any projection of simple continuity. Throughout the neofuturist aesthetic, this reorganization takes precedence over the mere development of an initial idea or theme.

In other futurisms, continuity has been a crucial aspect of the structure of their given works. Umberto Boccioni’s Futurist sculpture of a man running extends motion through time into physical space, revealing “unique forms of continuity” in its beautiful calculus of speed. Many forms of club music would simply cease to function without continuity — DJs strive to ensure that the rare break in continuity only heralds its return. Further, continuity is tied directly to the technological/industrial project in itself, as any stoppage in the continuous function of a machine, any disruption of the workflow, or any radical break in a typical structure can be costly. Neofuturism’s rupturing of continuity complicates its structure, revealing that forward motion through time can result not only in mere progress but also in a series of intricate and novel events that guide the future along unexpected courses.

Often, these events can cause breaks in continuity so drastic that they lack all resemblance to previous movements within the same track. On Oneohtrix Point Never’s “Freaky Eyes,” the first half of the track begins with swirling, tense ambience, out of which an organ melody arises, eventually accelerating as an alien vocal synth enters. The combined scene builds to a seemingly impossible velocity, signaling an oncoming climax — it then disappears into a single tone. In its place, just as suddenly, appears a brand new melody, a rock chorus. Lopatin gives us just a few moments to absorb the shift, then shifts drastically again, feeding the straightforward, sugary rock melody into a granular synthesis engine, tearing it to shreds until it too disappears, giving way to a descending synth line.

Through this section, multiple events occur that interrupt the seeming progress of the track. For the first (the chorus that follows the climactic acceleration), the audience expects something to occur; the forward motion of the track feels too overclocked as it reaches its maximum speed. But what actually occurs in the event feels utterly novel. First-time listeners would have no way of expecting a sentimental, alien-fronted rock chorus to result from that acceleration (unlike, say, the bass drop on Rustie’s “Coral Castlez,” from this year’s candy-coated EVENIFUDONTBELIEVE, which is apparent as soon as an ascending lead synth enters the track). The second event, the fractalizing of that chorus, fails even to signal its coming. It manifests unanticipated; the audience has barely processed the last major event, and our ears have barely adjusted to the radical shift in continuity. This instability, this absence of solidity, suggests a new reading of the future, in which the progressive incursion of technology offers neither predictable consequences nor even the opportunity to decipher successive, novel events.

Continuity-rupturing events, used frequently, can produce works of heterogeneous texture and complex form. Using a variety of singular or unpredictably repeating elements, a strange new structure can emerge. Through their use of a range of explosive sound-masses, streams of spoken text, and triggered samples, Rabit and Chino Amobi form the architecture of their epic mix THE GREAT GAME: FREEDOM FROM MENTAL POISONING. By packing such a massive variety of events occurring over the vector of time, they make identifying a central motif or rhythmic basis impossible. Even the massive synth explosions and frantic strings that occur most frequently can’t form a reliable reference point in the miasma of the mix. Although not lacking in coherence, THE GREAT GAME offers as its structure only an unstable background formed from elements of The Art of Noises playbook, but the structure’s instability actually undermines the hegemony of the industrial and military technology it mimics. The voices that alternately rise out of and interrupt the noise are equally heterogeneous. They don’t offer progress, but they do exhibit changes over the course of the work in the ways they claim authority, taunt the audience, and offer critique from the margin, their words working alternately as alarms and manifestos.

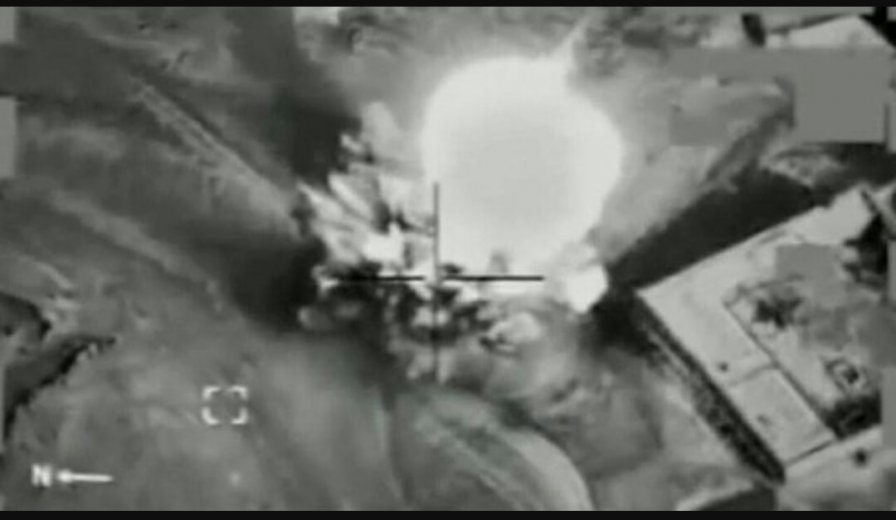

The violence that characterizes the explosive event does not always suggest a political agenda on the part of the artists, though their works are themselves violent ruptures in the continuity of musical aesthetics. The events these works depict, some of which do exhibit short-term continuity and progress, constitute a neutral but malleable unit-structure for neofuturist aesthetics. This unit-structure offers a perhaps more nuanced reading of the way time moves, in that it can accommodate a wider range of occurrences and outcomes than models of continuity and progress. The drone strike and the black-swan innovation, the unprecedented storm and the record-breaking drought, the zero-day exploit and the passing of the Turing test, the suicide bombing and the revolution: all are potential breaches in the continuity of history. Subjects can introduce new events into the temporal landscape, but potential actors are equally capable of becoming victims of these explosions. Even as they rupture the continuity of musical time, the artists of the neofuturist aesthetic cast a cold eye on the events within their works, attempting instead to locate a space for the life, thought, and acts of the individual subject amidst the state of emergency, hyperviolence, and systematic alienation that continue to unfold as the future arrives.

Deep Dreams: Liminal Zones in the Mutating Mass

Of course, neofuturism does not merely orient itself against other futurisms. It refashions the tools of futurism to orient itself toward the actual future, against the forces of stasis and status quo that organize the present (note that not all artists working in neofuturist modes endorse programs that are expressly political — orientation toward the future can take many forms, and each work offers its own problematic of the present). Arguably, technocratic futurism represents a capitalistic, reified form of the explosive post-industrial Futurism that engendered the term, and so it too represents a kind of stasis even in its desire for change and technical progress. It too is an aspect of the changeless, monolithic, one-dimensional consciousness that asserts its dominance in the ideology of the present. By contrast, the neofuturist aesthetic posits alternative spaces and processes that operate within the fissures and convulsions of the monolithic structure of capitalistic consumption and technological singularity. These spaces and processes mark the emergence of new possibility: for change, resistance, and liberation.

In employing processes that undermine changeless stasis, the neofuturist aesthetic subverts dominant paradigms of the shape of the future. While one primary method is the unexpected, explosive event, it also takes other shapes. Some of these artists use techniques that preserve temporal and rhythmic continuity but transform it into mutant, alien forms. Appropriately, Oneohtrix Point Never’s “Mutant Standard” exhibits this quality repeatedly over its eight-plus minute runtime. It begins with a thumping, pulsing bass sound, which creates a foundational motif for the track as it unfolds through the many shifts it undergoes. As it intensifies, more elements seep into the mix and brief ambient sounds sometimes take over space. When it returns, the bass track has morphed into an arpeggiated lead line, which continually mutates through different amplitude envelopes, eventually shifting again into a rhythmically continuous vocal synth cutup, and finally expending itself into a feedback-laden reverb cavern. This process models shifts in a current of events, offering neither climactic peaks nor constancy. It merely changes, never favoring one direction over any other, while still emerging in forms more and more alien to its origin. Operating on a simple rhythmic theme, Oneothrix Point Never uses these mutations to reveal the multidimensional possibilities inherent in its form. The track’s inability to remain still signals the impossibility of stasis, the necessity of change in the shifting sands of time.

Mutation can also work on the architecture of a piece (as opposed to working on a melody or theme within it). Full of strange and unexpected events, Lotic’s “Banished,” from the late-breaking Agitations, features a consistent vocal sample throughout its short runtime. Lotic manipulates the sample into alien, amorphous rhythmic structures that preserve little of the qualities of the original sample except for its stuttering intensity. A kind of continuity exists on “Banished,” in that similar sounds emerge in the recurrence of the shredded sample; however, the form that Lotic gives to the track renders the source unrecognizable, twisted into a new form. “Banished” represents its mutations as a kind of trauma, a forcible binding of the subject into tortuous, impossible forms. These mutations reveal the underlying violence in technological motion and monolithic culture, the subject’s cries mediated by the synthetic apparatus that confines it. The sheer chaos and complexity of “Banished” mock simplistic visions of progress. Lotic does not search for salvation in the glow of the machine; he seeks the subject hidden within the cybernetic mass.

This subject often finds itself banished to the margins, somehow both within and outside the mutating monolith. Artists in the neofuturist aesthetic have sought to expand this liminal space, de-emphasizing the central basis of a track (where such a foundation is even present) in favor of the elements that surround it, moving away from club music’s fixation on bass and lead lines. Holly Herndon’s “Interference,” from Platform, released in May, features a system of overlapping events, some recurring, some constant, some singular. With so many undercurrents and incidents in the track, it’s often difficult to follow the central, stuttering rhythm track. This heterogeneous mixture of rhythms, timbres, and other sonic elements undermines the track’s status as a use-value; by covering and corroding the dance-ready elements, and by including a multitude of liminal particles, Herndon offers a plurality of experiences to the listener, favoring no one over any other. De-centering the mix allows her chopped, vocoded vocals to occupy their own space, a liminal zone that emerges out of the seething, mutating mass; it’s neither axial nor hidden, but present, a voice whose language just barely touches the ear, a voice offering words with unknown but potential significance.

On Amnesia Scanner’s early 2015 release AS ANGELS RIG HOOK, this concern with decentralization extends to language itself (similar effects appear in the poem on the title track of Elysia Crampton’s American Drift). Jaakko Pallasvuo’s poetry running throughout the track follows no single stream of meaning, fracturing into a polyphony of voices and consciousnesses, offering vague prophecies of the future: a slag-grey ocean, “a stream of more-or-less violent crime,” augmented reality contacts, drone-powered wi-fi, hyperreal body modification, thunderdomes; “This could be us, but you’re playing,” a voice offers: your dreams and nightmares are not only possible, but also in your reach. Within the the liminal zone of poetry, here far from the spatially-distant rhythmic mass of the track, the dream can reach a tenuous reality in its status as art. Not merely a catalog of futuristic curiosities, these abortive but predictive snatches of poetry each create, in their brief passage across the cerebrum, a bubble-universe of futural possibility.

As the track continues, Amnesia Scanner slice language into grains, and these bursting, liminal bubbles cast off their particular significance into the void of potentiality, reabsorbed and yet separate from the mutant mass of the track. Invading the liminal zone, the synthesis engine has captured these bubble-worlds; in its attempt to assimilate the poetry deeper into the rhythmic mass of the track, it obliterates the language’s value as a world-generating force. What is left is a ghostly relic of meaning, a mute hologram of a subject cut off from its ability to critique and its ability to desire, a subject bound to the mutations of the mass, propelled into the future by a volition other than its own. Liminal zones are by their nature transitional and temporary, which renders them at once creatively powerful and extraordinarily fragile.

It’s precisely this power and this transience that make the zone beyond the technologized mass the ideal space for the neofuturist subject — the subject who seeks refuge from shattering events or who desires to create new worlds. This space operates both within the matrix of technology but also beyond it, in spaces that technology struggles to imitate and infiltrate: the natural world, the home, the human body. Encroaching into these spaces, the technocratic futurists seek to organize and data-mine all available resources to render them into use-values, at least insofar as the potential for draining more resources isn’t fully compromised (and often beyond that point, especially in so-called “developing” areas; see Rabit and Chino Amobi’s “New Age Chinese Drone Surveillance,” for instance). With respect to the subject, this is what Heidegger warned about in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology”: the opportunity to rescue the human race that technology possesses is precisely also the greatest danger to humanity, because in order to do so, the human race must itself become the object of organization by technology. In other words, the development of technology binds the human subject to a cybernetic structure, transforming humans into an order of resources controlled by the technical apparatus itself. This organizing gaze threatens/offers to infiltrate life so thoroughly that the full truth of the subject’s being will become known, compiled, and set in its appropriate place inside a matrix of data.

The achievement of this telos is the horizon of the transhumanists (and according to them, an inevitability). But the neofuturist aesthetic resists this model, even as the artists depict its encroachment. In this resistance, new horizons emerge.

The Man in the Dead Machine: Technology and Resistance

Where the Futurists concerned themselves with the beauty of technology as a raw, powerful force, neofuturist artists seek rather to investigate relationships between humans and the devices that surround them, however benign or sinister their influence. The neofuturist aesthetic derives beauty not from the form of technology itself but rather from the struggle of the human being that is fascinated or trapped within that form. It’s crucial to note that these artists are not mere Luddites; technology is not only crucial to their projects in the form of the DAW and VST plugins, but potentially also as a liberating force. The neofuturist critique of technology focuses on control and cybernetics, undermining the alienating, martial, penal, and seductive elements of technology in favor of values such as connection, liberation, resistance, and distance. In the music, these values most apparently manifest through the artists’ manipulation of the human voice. Although the harsh, digital texture of the neofuturist aesthetic is one of its defining elements, the voice plays a surprisingly crucial role in many of the works within it. The voice easily encodes a human subject, which, juxtaposed with the various other sonic elements, can allow the artist to swiftly locate a consciousness in their work.

The neofuturist aesthetic derives beauty not from the form of technology itself but rather from the struggle of the human being that is fascinated or trapped within that form.

Rabit and Chino Amobi’s THE GREAT GAME displays a polyphony of human voices, but the most central — emerging, as SCVSCV describes so vividly in his review, out of “explosive dust, mech-fire, and a sudden, surprisingly serene ambience” — is James Baldwin’s, reading his poem “Staggerlee Wonders.” Baldwin’s voice insists: “Manifest destiny is a hymn to madness/ feeding on itself, ending/ (when it ends) in madness:/ the action is blindness and pain,/ pain bringing a torpor so deep/ that every act is willed, is desperately forced…” Unlike many of the other voices that appear in the vast structure of THE GREAT GAME, Amobi and Rabit allow Baldwin to speak unironized as he details the torpor of pain that shoots through both the colonist and the colonized. Amidst the flames of a global hell dominated by a sense of its own destiny, the mad, pain-stricken destroyers burn the globe out of fear of their own destruction. The torpid pain that inhibits action against the madness of manifest destiny is a crucial aspect of the difficulty of resistance; it renders all action in the language of violence, of explosion.

We often see this torpor manifest directly in the vocal elements of the neo-futurist aesthetic. Throughout Oneohtrix Point Never’s Garden of Delete, the “voice” (actually a voice-synthesis engine) of a fictional alien known as Ezra sings the melody. Ezra, pubescent, mutating, with “an abject cluster of slime stuck behind his tonsils [that] made it difficult to make out what he is saying.” His single facial expression makes it impossible to pinpoint what he is feeling, though it is clearly some sort of pain. Struggling against the condition of his melting, alien body, Ezra fails to communicate, unable to signify. In the album, his technologized voice slips into the texture of the digital sounds, cut up, granulated, hidden, with his lyrical content, his emotion, his language buried under the veneer of DSP and production techniques. Ezra’s infinite loop of pubescent pain, hidden in the matrix of digital data, mirrors the inescapable torpor of alienation in a world where technology mediates the very possibility of expression and communication. Words slip into the void; and, far beyond Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock, who struggles to say just what he means, the alienated voice struggles for an audience that can even understand him. Flattened into data, the subject craves empathy, externalizing its inner life into the digital medium in hopes that someone might decode it, in hopes of an effective transmission of his pain, a single, efficient action, however transient, across the digital divide.

The same clipped, fragmented, and often vocoded vocal sounds appear on Holly Herndon’s Platform (see especially “Chorus” and “DAO”). However, apart from the ASMR-whispering pleasure dome attendant on “Lonely at the Top” (who modulates her voice in order to provide a pleasurable service climate, communicating only empty platitudes about success), one of the places where Herndon gives the clearest freedom to the voice is on “Morning Sun,” a bubbling celebration of dawn. Amidst half-uttered phrases, imperatives to wake up, and melodic snippets, Herndon’s speaker admits vulnerability, but stakes her freedom on the rising sun: “In the morning sun I will be gone.” The rising sun, as always, represents both future and possibility, but here it represents a kind of freedom at the cost of comfort and dreams. The speaker, cold but awake, steps out of the bedroom, beyond the liminal plane and toward a concrete possibility: the horizon of autonomy. Although not all of the artists working in the neofuturist aesthetic offer such an explicit image of what exists beyond the liminal zone, it’s clear that hope relies on awakening — that is, a mutation within human consciousness. But it also relies on the coldness before sunrise — in discomfort, but also in self determination. The possibility of love that waits on the horizon can’t be reached by force or by resting comfortably in dreams: it can only be reached by choice.

Returning to THE GREAT GAME, the mix’s latter pieces now come into focus. The “geopolitical explosions” scattered across its runtime have coalesced into an unreadable pattern of violence; the mutating, technical monolith has reabsorbed the bubbles of liminal space that have chanced to occur; and the subject, running/fleeing/charging across the cinematic backdrop of these events arising and collapsing, now appears in the gaze of the robotic narrator: “Nine out of ten doctors recommend never coming for me in your life. Yet you still tried it.” Having repeatedly warned the listener-subject that “the stakes are high,” the authoritative voice affirms the courage of the subject under her gaze. No longer warning the narrator against the dangers of playing the game, the narrator launches a new program: “Rules must be broken… We must act very soon or the window of opportunity will close. Most of you have never tasted freedom in your lifetimes. We still do have a chance to change that.” We should question the voice’s emphasis on purification and its conspiratorial stance, but such an alliance with technology may be necessary to achieve effective resistance, to mutate the vector of the future so that it touches a new horizon, so that the telos of history emerges as liberation and not domination.

Neofuturism is not a political program. It is a set of shared values that, in their aim toward the future as becoming, manifest an ultimate intention toward liberation. Its use and critique of the vast applications of technology form a primary basis for these valuations; technology reflects its users and makers. However, these aesthetic, political, and cultural values do not fully encompass any individual work in the milieu. Countless variations exist, with different central issues: queerness, mystical communion, science fiction escapism, movement/dance, racism, violence, pure sound. Despite the variety of issues within the aesthetic, each of these possibilities unites with the rest in technical and metaphysical aspects.

Perhaps most primarily, each of the works within the neofuturist aesthetic aligns itself against the current, reified vision of the future, replacing it with a new possibility, a new hope, a potential dawn.

Conclusion: For the Sake of Future Days

What the neofuturist aesthetic offers is not a mere escape, but a counterfuture (though some works skew more towards an escapist option). By manifesting a variety of visions and by critiquing the images proposed by other futurisms, the artists working within this aesthetic reach toward new possibilities, both for avant-garde music and for the globe. Other forms of expression provide alternative approaches to similar problems, but they focus their energy in different directions. Noise artists, for instance, have often applied relentless and arresting critique to images of the present that suggest loss and decay; see for instance Prurient’s 2015 masterpiece Frozen Niagara Falls, where Fernow shouts “THE FIRE IS SLOWLY DYING.” Hip-hop, too, can take the form of a relentless critique, but its gaze typically focuses on past and present circumstances; however, see Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” from his masterful To Pimp a Butterfly for a glimpse of hip-hop’s gaze turned toward the future and revolutionary possibility. Many other artists use similar digital techniques as the neofuturists, but focus on club music, decidedly present-focused due to its need to provide a rhythm for the audience’s contemporaneous ecstatic motion; Jlin’s Dark Energy provides an excellent example of this technical link. And since, unlike the Futurists of the early 20th century, the artists working within the neofuturist aesthetic form ideas primarily as solo artists (who occasionally collaborate); some works align more directly with the values discussed here than others. Like any idea with a global scope, the neofuturist aesthetic manifests in many forms, some more paradigmatic than others.

What the neofuturist aesthetic offers is not a mere escape, but a counterfuture.

It seems crucial, however, that it has emerged now in 2015. While I wrote this article, the “geopolitical explosions” of the November 12 and 13 terrorist attacks unfolded in Beirut and Paris, committed by a group bent on a radical vision of their destiny: an apocalyptic Islamic state. Around the globe, people flocked to their devices to announce their views on the matter, Anonymous declared war on ISIS and hacked their Twitter accounts, bombs dropped on civilians and militants alike, and the world seemed to sink somehow deeper into a dystopian wonderland of violence and digitality, miscommunication and factioneering, war and videos of war. Meanwhile, virtual reality goggles will roll out in time for Christmas, Edward Snowden finally got a social media account, and we’re a month and a half past Back to the Future’s most distant vision of our potentiality. A critique of technology feels not merely timely, but utterly vital as a tool of orienting a culture with an unclear potential. Reclaiming the future and refiguring its shape is a pivotal stage in wresting liberation from those who would institute their vision of the future by force.

The counterfuture that the neofuturists offer is not a bright utopian response to the dystopian elements of the current global situation, but a nuanced approach to a future that dreams of liberation, glimpsing it as possibility. It’s no surprise that the artists working in this mode often tie their vision directly to consciousness and the sacred. The liminal zones where this work takes place already breathe with new spirit, an anarchic energy that affirms existence even in its denial of the present. Will we find our way back to the garden? Or do we march inexorably toward the birth of synthetic gods, intelligences that will rule like Gnostic archons over a blighted, post-industrial wasteworld? Time will tell. Whichever direction we pursue, visions of the future will guide us there. From distant horizons, they reflect back our potentiality, our dreams, our fears. If there is hope left for liberation, art presents an opportunity to discover it, amidst storm and strife, in the images that carry us beyond this world and into the next.

More about: 2015, Amnesia Scanner, Arca, Chino Amobi, Container, Elysia Crampton, Holly Herndon, Janus, Jlin, Kendrick Lamar, Lotic, M.E.S.H., NON, Oneohtrix Point Never, Prurient, Rabit

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series