We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series

Obama’s dirty secret is how he spends his time alone. Each night after dinner with his family, he removes himself from all company, and late into the night — with seven lightly salted almonds — he focuses in the personal quiet of the White House’s Treaty Room. There he reads letters that have been addressed to him, works on the next day’s speeches, catches up on current news, and perhaps allows the light background presence of a game (if one of his teams is on). When The New York Times reported this long-running practice of Obama’s, it was already quite late in the president’s career, and it came out as a mild, little-known narrative factoid — nothing too noble and nothing too astounding.

How did our past presidents become publicly intimate? FDR held his “fireside chats” — prototypical stagings of familial intimacy at the dawn of live mass communication. John F. Kennedy forced the public to engage with the corporeality of public figures through his own death: a horrific reduction of the world’s foremost figurehead — the president, an emblem of power and values — to a precarious organism, shattered and splayed against car seat leather and the first lady’s dress. Then, in another event of blowing up, Bill Clinton’s intimate life erupts with the graceless event of a sex scandal. Here lies the context for the cheeky New York Times headline that frames the outing of Obama’s late hours of solidarity: “Obama After Dark: The Precious Hours Alone.”

Obama’s contribution to the lineage of performances of public intimacy by US presidents is stunning, because it is subtle and silent in this case. Barely noticeable, those several hours that the president spent alone every night for the past eight years were self-gratifying and unannounced, bearing the integrity of their commitment to the real as opposed to the spectacular. In his separation, however mediated it may be, Obama finds a moment of personal repose.

Chance Meeting

There is so much that can be (and has been) said pointing toward the ways in which the presence of the spectacle — as postulated by french philosopher Guy Debord in 1967’s The Society of the Spectacle — has only become more apparent and imposing in the five decades since its postulation. It has become painfully clear that Debord was correct when he wrote that while the early economic domination of social life “entailed an obvious downgrading of being into having that left its stamp on all human endeavor,” we currently exist in the stage of domination that “entails a generalized shift from having to appearing” (emphasis mine). Debord continues: “all effective ‘having’ must now derive both its immediate prestige and its ultimate raison d’etre from appearances.”

The spectacle, in short and in so far as I will use the concept, represents the alienation suffered through the fragmentation, totalization, and representation of social experiences as they are mediated by economic technologies, including the spectacle’s “most stultifying superficial manifestation,” the mass media, a technology now partially understood as the online media through which we receive new terms of self-presentation and connectivity. As significance is more greatly represented and understood through follows, likes, and shares — regardless of whether or not the originating event of those engagements (the performance of a song, the end of a relationship, the brutality of police, etc.) was at all concerned with online significance — it becomes clear that the veracity of being has shifted in some degree to appearing. In that shift, being is hyper-stimulated, ever present and presentable.

Ben Ratliff writes on music in this age of hyper-representation and alienated non-meaning in his recent book Every Song Ever. He lends an approach toward coping with (and perhaps appreciating) saturated cultural abundance. Each chapter outlines a different quality found in music across vastly different sources (these are broad qualities: slowness, fastness, loudness, silence, repetition, etc.), suggesting that if one can find what is to be appreciated about any piece of music they come across, they are more well-prepared to traverse the contemporary music listener’s landscape of hyper-availability and algorithmic introduction. Ratliff’s enticing sense of openness when listening is valuable insomuch as it lends itself well to acceptance, appreciation, and tolerance. However, in its endgame, it turns the listener into a fine-tuned processor of the cultural noise of music genome models like Pandora and Spotify Radio, a post-Fordist interpreter of the endless data-curated mix.

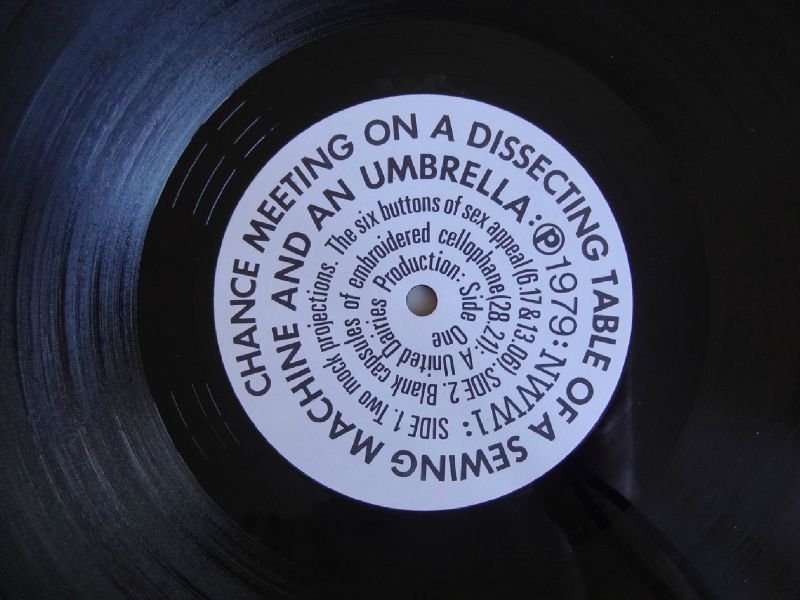

Two somewhat recent articles come to mind for illustrating the pitfalls of becoming Ratliff’s ideal listener: (1) this article about DJ Screw by clipping.’s William Hutson, which begins by expressing frustration at the elevation of DJ Screw’s music without an appreciation of the southern rap that begot it; and (2) this L.A. Weekly article outlining the cultural thrust of a particular list of “weird” music artists donned on the artwork of the Nurse With Wound album Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella, a “Rosetta Stone, in the form of a cryptic list of names looking for the right person to decode it.” Each of these takes on music appreciation values the listener’s cultural experience and point of reference over their analytical (or even emotional) comprehension of a piece of music. While Ratliff’s listener simply copes with the anxiety of listening within our current manifestation of the spectacle, the above stories remind us that music mediates — and is mediated by — culture. The positions of the geek (the fanboy) and the specialist (the collector) are the ones who better grasp the social meaning of musical life, standing with their feet in the soil of being and having, respectively.

Scrolling (Fall Forever)

Last month, I deactivated for the first time, although I’d always known my day would come. My Facebook habit filled the tiny cracks in my day until I came to self-diagnose bouts of scrolling as signs of unresolved anxiety. If a moment could be deemed too short to actually work on a task, it was the perfect amount of time to scroll for a mild fix. Days went missing in the form of lethargic, slow-burning panic attacks.

Somehow, I found comfort this year when I got around to reading Tao Lin’s Taipei. The novel is heavy with drug use such that it renders itself as an ever-collapsing tranquilized daze. Taipei’s protagonist Paul makes an island of himself when he loses a sense of relation to others beyond the drugged experiences shared with them. Throughout the novel, this drug/relation theme is forcibly entangled with an experience of internet connectivity. Lin writes:

In mid-June, one dark and rainy afternoon, Paul woke and rolled onto his side and opened his MacBook sideways. At some point, maybe twenty minutes after he’d begun refreshing Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Gmail in a continuous cycle — with an ongoing, affectless, humorless realization that his day “was over” — he noticed with confusion, having thought it was a.m., that it was 4:46 p.m. He slept until 8:30 p.m. and “worked on things” in the library until midnight and was two blocks from his room, carrying a mango and two cucumbers and a banana in a plastic bag, when Daniel texted “come hang out, Mitch bought a lot of coke.”

When confronted by hyperactivity, it’s easiest to be passive, to sway against its tides.

Months later, having just graduated from college, jobless and decidedly “surfing couches for a bit,” I hear Car Seat Headrest’s Teens of Denial and, frankly, it helps me a lot. Our own Rob Arcand relates it to the “now-unfashionable texts of Alt Lit figureheads like Tao Lin, Mira Gonzalez, Melissa Broder, and others,” by lending it the same descriptor they were given: New Sincerity. Teens of Denial is oversaturated with expressions of disaffection, hopelessness, self-disappointment, and aimlessness delivered with well-calculated detachment. When a listener receives the recursive singalong hook to “(Joe Gets Kicked Out Of School for Using) Drugs With Friends (But Says This Isn’t a Problem),” they can’t be sure on what level they must take it: “drugs are better with friends are better with drugs are better with friends…”

It’s a simple line and, in its context, can easily be judged as tragic. Nonetheless, I soberly take it as a maxim for relation, a reminder that shared experiences of any form and quality really do surpass our obligations to having and appearing.

I often think about an article my friend Ty shared on Facebook something like two years ago. I’ve searched it and re-searched it, read it and re-read it again and again since then, always thinking I’ve finally put it to rest. It’s called “We Are All Very Anxious,” and it was published by the organization Plan C and the Institute for Precarious Consciousness. Its subheading is “Six Theses on Anxiety and Why It is Effectively Preventing Militancy, and One Possible Strategy for Overcoming It” and its argument is thorough, nuanced, and too refined to do proper justice here. In short, however, it claims that “[i]n contemporary capitalism, the dominant reactive affect is anxiety,” and that this is a public secret, which is to say that it is “something that everyone knows, but nobody admits, or talks about.” Thinking back to my own dependency on (and eventual aversion to) Facebook, Ratliff’s coping with musical hyper-availability, and Obama’s nightly repose away from company, I consider the following that Plan C has to offer:

Today’s public secret is that everyone is anxious. Anxiety has spread from its previous localized locations (such as sexuality) to the whole of the social field. All forms of intensity, self-expression, emotional connection, immediacy, and enjoyment are now laced with anxiety. It has become the linchpin of subordination. […] It is difficult for most people (including many radicals) to acknowledge the reality of what they experience and feel. Something has to be quantified or mediated (broadcast virtually), or, for us, to be already recognized as political, to be validated as real.

The public secret functions on the predicate that feelings are insufficient as sources of meaning. Artists, musicians, writers must acknowledge this and interrogate it if they wish to radically exhibit the nuances of feeling and rethink forms of political art. Perhaps art, so long as the art under interrogation is non-presumptuous and hazard-less, is the one field in which one should never need to make claim of their validity. Perhaps self-gratifying art will always be understandable.

2016 has been marked with constant news of denied validation to many: the DAPL battle, the Brexit decision, the unending stream of racialized police violence in the US, and the general narrative and outcome of the US elections, to name the most prominent examples from my point of reference. When facing such denial, it helps to remember that each of us is valid and can act in a multitude of ways. When Trump was elected, I felt powerless and ashamed. I joined others in the streets of Los Angeles, which felt good, but didn’t always satisfy the lowness that I woke up with for days and days. I felt small and silent. My hope is that, in the wake of an election that proved in part that loudness, performances of surety, and self-righteous hate speech could be so easily exploited within politics, it will become increasingly valuable to embrace introspection, nuanced uncertainty, and intimate vulnerability, executing these traits by means honest to our goals.

On Vulnerability (“Some day in bravery/ I’ll embody all the grace and lightness”)

It feels to me that, in the arts, collaboration and communion will thrive.

In an essay called “The Friend,” Italian philosopher Agamben explores the implications of friendship: “What is friendship, in effect, if not a proximity such that it is impossible to make for oneself either a representation or a concept of it? […] The friend is not another I, but an otherness immanent in self-ness, a becoming other of the self.” He comes to understand that two who are friends can never understand one another outside of their sharing of the “experience of friendship,” and much in the same way, a friendship can’t be interpreted by one who is outside of it because “friendship is neither a property nor a quality of a subject.” If collaboration and cooperation is going to resemble friendship, voices will meld together, they will contort each other’s speech, amplify and support one another, and in all those acts become indistinguishable.

While on tour this summer, one of my bandmates played Frankie Cosmos’s Next Thing for about a quarter of the time she spent driving. All of us had already heard and liked the album (and some of us quickly grew sick of it in this time), but it was then that I personally met the album where it was at. Among the intimate bundle of friends that were my tour-mates, I felt connected to the content of Next Thing. Greta Kline — singer, guitarist, and songwriter behind Frankie Cosmos — writes lyrics that are at once confessional and self-distancing. There’s nothing particularly revolutionary in the plain-speech, journal-entry-style musings that float atop the band, but there is quite a lot that can be said about the brevity and clarity of Kline’s epiphanies as they heed the lessons of terse, vulnerable writing by Frank O’Hara, Eileen Myles, Ted Berrigan, Kimya Dawson, Paul Baribeau, and the like.

“Embody” is an ode to the elusive quality of illumination that one finds when they gaze at their friend. Kline insists: “Sarah is a lightbeam/ From the picture Jonah sent me/ It makes me so happy she embodies all the grace and lightness.” Because we can’t examine the specifics of Kline’s claim for ourselves, we prefer to consider whether we have felt the same way toward others, our own friends. “Embody” is an ode to friendship without the specifics of the friend. It is relatable and peculiarly human in its lopsided phrasing and deceptive arrangement: small formal units, elastic pulses, and slight alterations in harmonic patterns confuse a listener from the song’s simplicity, if only for the briefest moments.

The entirety of Next Thing is built around a precarious base like this. Kline’s simple lyrics are dressed up with equally simple parts, the delivery of which, however, are intricately nuanced. Exemplary of this is the short, bittersweet “Tour Good.” The band in an equivalent to unison, following each other through expressive tempo fluctuations, feels at once unstable and compassionately united. Following the call of “I don’t know/ What I’m cut out for,” rumble-strip-steady floor toms eb and flow with Kline’s tour mood. The asphalt of the simplest rock beat is revealed to be slippery. When pressed on, surprisingly, it gives, it supports in any way it can. At the end of the short verse of a song, in rare harmony, voices half-heartedly sing, “You change, I change, hooray.” Frankie Cosmos redefines musical excellence to contain restraint and sensitivity. Next Thing presents the sound of a band moving as a unit, reinforcing and amalgamating under a steady voice with self-assured intent. Hearing it with others has always been best.

In February came the release of Looking Around, an unlikely two-track album by seasoned experimental composers Michael Pisaro and Christian Wolff. The album is the barebones documentation of an improvised session between the two, two who are not particularly known in their already well-formed careers for being improvisors. What occurs is a drifting, meandering, non-resolving expanse of indecision during which musical ideas are exchanged but not in any such way that a particular musical moment can be ascribed to one or the other member. The release is humble in concept, execution, and presentation. It is a recording in which music is not the end-all be-all or even particularly the goal in mind. In the humility of Looking Around, Pisaro and Wolff present a snapshot of a vulnerable trusting friendship.

Openness and elevation, as both occur between vulnerable parties, lend to increased understanding and support.

On (un)Certainty (“don’t forget to show everybody you’ve ever known”)

It is equally important for us to rebel against the encompassing predicate that we must all be reporters and that our success as such is the means of our worth.

Semi-satirical pop band Kero Kero Bonito released the fantastic album Bonito Generation this year. Among its many subversively witted singles is “Picture This,” a cool-minded hit about the instant joys but possible pitfalls of photo-sharing. Vocalist Sarah Bonito delivers its chorus: “Hold your camera high and click/ Exercise your right to picture this/ But don’t forget to show/ Everybody you’ve ever known.” Later in the song, she plainly references the oft-recited, doublespeak “pics or it didn’t happen,” always an insincerely sincere plea to accommodate to the demands of our stage of the spectacle: appear.

“Picture This” is a sharply uncertain query launched at the demand to be present digitally. It is a hypothetical dwelling on Plan C’s acknowledgement that “something has to be quantified or mediated (broadcast virtually) […] to be validated as real.” As a user becomes more dependent on posting (and receiving the likes and comments that follow) to interpret their life, they lose the ability to determine value and meaning on their own terms.

Facebook politics are notoriously non-conducive. Often, value is awarded to the user who is most sharply-worded, firm-footed, and armed with more like-minded onlookers. The sort of behavior that Facebook prioritizes arises out of anxiety, the kind we are forced to feel when any act of speech is not only an instance of thought-sharing, but also an irreversible and highly visible instance of identity formulation and performative representation. On Facebook, we are watching ourselves squirm under the laboratory lights, stoked on the smallest morsels. As opposition is devalued and often punished, the user enters the echo chamber and rehearses their ideology, becoming more like their preconceived self.

Dissonance is researched — basked in — across N-Prolenta’s A Love Story 4 @deezius, neo, chuk, E, milkleaves, angel, ISIS, + every1else…. and most of all MY DAMN SELF. On “Query As Prayer,” against buzzing and flighty violins, N-Prolenta declares, “I am mortar […]/ Even though I crumble/ And cling to my own body still/ The air becomes my lover/ And to it I am bound/ So stagnant, my image […]” (transcription mine, errors possible). As much as I can understand it, this query is a gesture, a focused and defiant assertion of selfhood as it is pushed out of its place. It is an expression of feeling amidst assertions that one has no right to feel such a way. manuel arturo abreu extrapolates in an article about A Love Story… for aqnb:

The music simultaneously expresses the damaging feeling of apophenia (seeing patterns in ostensibly meaningless data) and acute isolation that result from noticing the invisible antiblack underbelly of civil society. White respectability convinces the witness of antiblackness (across history and in the present) that what one experiences so consistently and insidiously is not a pattern, but random exceptions to an overall progressive context.

Uncertainty is common for me in my anxiety. The more I am told, the less I feel I know. Nonetheless, I wish to elevate my trust in those I am near.

On Introspection (“my DAMN SELF”)

On 2012’s channel ORANGE, in the aftermath of the murder of Trayvon Martin, Frank Ocean delivered “Crack Rock,” a politically charged anthem against particular systemic racial injustices in America: the crack epidemic, class divide, and state violence. Of those, he laments, “Crooked cop dead cop/ How much dope can you push to me/ Crooked cop dead cop/ No good for community/ Fuckin’ pig get shot/ 300 men will search for me/ My brother get popped/ And don’t no one hear the sound.” There is no doubt that this is a potent moment on an album that otherwise showed its singer shying away from explicit statements much larger than himself. It is also of note that this statement lands so eloquently only months after Martin’s death (perhaps the first of many public black deaths sensationalized in tandem with mass public outrage) and almost exactly a year before the 2013 formation of the Black Lives Matter movement.

From this point, Ocean’s career narrative takes a dip. In the aftermath of his acclaimed and beloved debut, he draws back from the public eye and acts with discretion. Anticipation builds for a follow-up, and of course, it becomes harder and harder to speak. This year, breaking the four-year silence, we received Endless and Blonde, two broken masterpieces of different nature to channel ORANGE. On “Nikes,” Ocean riffs and delivers: “R.I.P. Trayvon, that nigga look just like me.” Now focusing on his own transference of the event of Martin’s death four years ago — much like Obama famously did when in the aftermath he stated “If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon” — Ocean’s demeanor of address has shifted from the all-encompassing analytical call to action of “Crack Rock” to a confessional attempt at relation. Ocean’s 2016 output has been noted as “eager to disappear” in the case of Endless and as “a hasty, albeit, beautiful, college final,” in the case of Blonde, which, as that reviewer noted, carried several alternate covers and contradictory album title spellings (the feminine “blonde” that Apple Music sported or the masculine “blond” on the cover).

Frank Ocean’s step out of the limelight was a broken undoing of the well-together mastery that bound together his Grammy-winner channel ORANGE, a recoil from the burden of representation topped off by a reluctance to submit to that same institution.

A similar gesture of stepping down can be found in the story of the Olympia hardcore band G.L.O.S.S. (Girls Living Outside Society’s Shit). G.L.O.S.S. moved quickly this year releasing their debut EP, skyrocketing to unforeseen popularity, and publicly disbanding within months. Their breakup letter read:

G.L.O.S.S. has decided to break up and move on with our lives. We all remain close friends, but are at a point where we need to be honest about the toll this band is taking on the mental and physical health of some of us. We are not all high-functioning people, and operating at this level of visibility often feels like too much.

We want to measure success in terms of how we’ve been able to move people and be moved by people, how we’ve been able to grow as individuals. This band has become too large and unwieldy to feel sustainable or good anymore — the only thing growing at this point is the cult of personality surrounding us, which feels unhealthy. There is constant stress, and traveling all the time is damaging our home lives, keeping us from personal growth and active involvement in our communities. Being in the mainstream media, where total strangers have a say in something we’ve created for other queer people, is exhausting.

The punk we care about isn’t supposed to be about getting big or becoming famous, it’s supposed to be about challenging ourselves and each other to be better people. It feels hard to be honest and inward when we are constantly either put on a pedestal or torn down, worshipped or demonized. We want to be whole people, not one-dimensional cartoons. […]

Thinking about this pressure of significance, and the toll of disfiguration that it plays on a subject, I turn back to Agamben. In his essay “Threshold,” he incorporates an illustration of the Flamen Diale, “one of the greatest priests of classical Rome.” He continues:

His life is remarkable in that it is at every moment indistinguishable from the cultic functions that the Flamen fulfills. … Accordingly, there is no gesture or detail of his life, the way he dresses or the way he walks, that does not have a precise meaning and is not caught in a series of functions and meticulously studied effects. As proof of this ‘assiduity,’ the Flamen is not allowed to take his emblems off completely even in sleep; the hair and nails that are cut from his body must be immediately buried under an arbor felix (that is, a tree that is not sacred to the gods of the underworld); in his clothes there can be neither knots nor closed rings, and he cannot swear oaths; if he meets a prisoner in fetters while on a stroll, the prisoner’s bonds must be undone; he cannot enter into a bower in which vine shoots are hanging; he must abstain from raw meat and every kind of leavened flour and successfully avoid fava beans, dogs, she-goats and ivy…

In the life of the Flamen Diale it is not possible to isolate something like a bare life. All of the Flamen’s zoe [“nature”] has become bios [“culture”]; private sphere and public function are now absolutely identical. This is why Plutarch … can say that he is hosper empsuchon kai hieron agalma, a sacred living statue.

We are now in a process of making ourselves much more like the flamen diale. Our culture functions doubly as a form of surveillance, not just by those who govern us, but also by all who participate in it. For us, every act of publicity, representation, and sharing is an irreversible act of fashioning the political self, which is perhaps part of why we are all so anxious.

Some might consider what I’ve said a lecture against being angry and taking a stance, but I know those traits shouldn’t vanish from every day social and political practice. I also know that my belief that those characteristics can coexist with vulnerable openness and ambiguous presentation of thought comes from a privileged position and may speak to one as well. I have taken this long form to consider things that I can’t close off and to present a survey — which is incomplete, lacking among others: collaborative practices of Elysia Crampton and Sean McCann; self-assertion through exploratory vastness by Fear of Men and Dedekind Cut; fragmented suggestions by Marissa Anderson and Tony Molina. In considering how I can leave this open, I turn to poet/photographer/musician/friend/collaborator Lora Mathis and their explanatory post about the concept of “radical softness.” The post is loosely about developing concepts publicly, about how theories can be written collectively and gradually through critique and conversation. Lora writes:

I’ve read a lot of critiques about radical softness and they’ve helped me develop my own thoughts further. When I first shared work online about this idea it was such a baby thought, yet people treated it as a developed movement that had clear, concise intentions. […]

I am sucking on critiques I have read. […] I am thinking about all of them and figuring out better ways to articulate myself. Language is important. Being clear & getting feedback is important. I’m working on things. […]

I have gotten criticism in my personal life about “preaching softness” and yet being rude to someone. Being soft is not about being docile. It is not about not having an opinion. I am more tender with myself than ever, but I also am learning to deal with my aggression and anger. I will not tell others to not be violent. I will not tell others to not be violent. I understand that these are valid reactions to oppression.

I am intimate and soft with myself and those close to me, but I will not be nice to those who are abusive. I will not take someone’s shit because they believe to be soft is to be kind, always. I will not be walked over. I will not be non-violent or quiet.

This is not softness to me. Softness is powerful. It is about healing. It is about inner-strength. And strength means standing up for yourself. It is not about forced passivity.

More about: 2016, Car Seat Headrest, Christian Wolff, Frankie Cosmos, Kero Kero Bonito, Michael Pisaro

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the year. More from this series