Film festivals are fickle beasts. In L.A. in particular, the Hollywood apparatus demands its penance in the form of red carpets, studio debuts, and galas — the type of occasions that sadly have a stranglehold on this town and are often forcibly fitted atop the cinematic events occurring within its borders — so any festival of national or, in the case of AFI Fest, international import must bear its veneer and pay homage to its annual contributions. In addition to that omnipresent force, AFI Fest has the misfortune of locating itself in the historic Grauman’s (née Mann’s) Chinese and Egyptian theaters. They are certainly fantastic theaters in their own rights, especially the Egyptian, which houses many of our fine city’s retrospectives and classic double features, but they also happen to be situated right at the corner of Hollywood & Highland which, for those lucky enough to never have driven in Hollywood, is the equivalent of driving straight into the devil’s asshole on an especially humid day in Hell.

Despite the inherent drawbacks of hosting any event in the heart of Hollywood, the American Film Institute admirably continues to do its best to present films from all over the world, of all sizes, scopes, and perspectives, with enough to please all cinematic palettes. It’s not quite on par with the New York or Toronto Film Festivals, but you have to admire a festival wherein you run into the co-writer/director of “I Sit Down When I Pee” and the weirdest real commercial in the history of mankind (Eric Wareheim promoting Quentin Dupieux’s Reality) and only a few days later catch the latest five-and-a-half hour arthouse endurance test from Pilipino director Lav Diaz. For as middlebrow as this town can be and as segregated, outside of a few select venues, as its high and lowbrow cinema experiences often are, it’s nice that AFI Fest at least attempts to bridge that gap, even if tailoring a bit more toward the low would make it a more well-rounded festival.

Aside from the handful of galas, which make up the majority of the week’s dose of glitz and glamour, the festival has remained intimate and well-organized considering its tradition of offering free tickets to the public. There was one disaster at the festival with a massive mix-up at the screening of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice wherein only 20 of the hundreds of people waiting for hours in line, with tickets, were allowed in because celebrities and studio guests had already taken up nearly all of the 600+ seats available at the Egyptian Theater, leaving an angry crowd of festivalgoers to wonder why they released so many tickets to the public when this screening was clearly not meant for them. Whether it was a matter of the studio bullying their way into as many seats as they wanted or the festival’s lack of foresight, it left a sour taste in a lot of people’s mouth. Thankfully I wasn’t unlucky enough to even get tickets to that one, so my suffering was kept to a minimum that night.

Unfortunately, due to my schedule, I wasn’t able to indulge in as many films at the fest as I had in prior years, but I was at least able to catch a few of the bigger highlights, one remarkably bizarre head-scratcher, and my first taste of a new arthouse sensation.

Clouds of Sils Maria

Dir. Olivier Assayas

Olivier Assayas is something of a chameleon. He is equally at home with intimate dramas (Cold Water, Clean), international thrillers (Demonlover, Boarding Gate, Carlos), ensemble pieces (Summer Hours), and meta-textual examinations of the nature of film and acting (Irma Vep). Clouds of Sils Maria fits firmly in the latter group, and while it shares a similar atmospheric style, pacing and pathos as his other films, it may be his most complex and rewarding one to date. Centered on Juliette Binoche’s Maria, who 20 years after giving her breakthrough performance in a now-famous play is asked by a prodigy to play the older female character in the film across a young rising star with Lindsey Lohan-esque tendencies, played with comical precision by Chloe Grace Moretz. As Maria rehearses her lines with her attractive young assistant (Kristen Stewart), she grapples with her place within the industry as an older woman and struggles to relate with the character she now plays and increasingly begins to resemble. Assayas has crafted a powerful film about identity and nature of contextualization in art and performance, blurring the lines between the realities of his film and that of the play being rehearsed, deftly conveying the double-edged sword art wields in its ability to enlighten and enhance life but also reflect all that lies hidden within us. Balancing its philosophical and psychological concerns with a light comic touch, Clouds of Sils Maria managed not only to be the highlight of the fest for me, but of Assayas’s career as well.

Jauja

Dir. Lisandro Alonso

Imagine Carl Theodor Dreyer, with a dash of Herzog, directing a surreal 50s Technicolor western and you might have some idea of what to expect from Lisandro Alonso’s baffling yet transfixing Jauja. Shot in the 4:3 aspect ratio, with rounded corners that give it the look of picture slides, Jauja’s every frame is that of a painting, carefully composed with a bright, otherworldly color palette taking the film into the hyper-real depths that lay buried within myth and the wormholes of cinematic narrative. The myth of Jauja — that everyone who searches for it and the infinite riches that lie within will eventually become lost — is taken to its logical (and illogical) extremes as Gunnar (Viggo Mortensen) searches for his missing daughter across the utterly alien landscapes of Argentina and Peru, where walruses appear through waterholes in the ground and a mysterious ragged dog has the only key to the map. The film’s initial concerns of historical imperialism and puritanism slowly dissipate as Gunnar’s journey, or more accurately, wandering, takes on a purely metaphysical form as history, myth, and character merge into the singular concern of cinema itself. The “lost” referred to in the opening lines is not geographical or psychological, but cinematic, as Alonso carves avenues for his narrative that, in the last 15 minutes, are more bizarre, perplexing, and invigorating than anything since Inland Empire. The images are as uniquely astounding as they are mystifying, and the shot of clouds slowly covering the stars as Gunnar rests helplessly on his back is the most singular and memorable shot of the year.

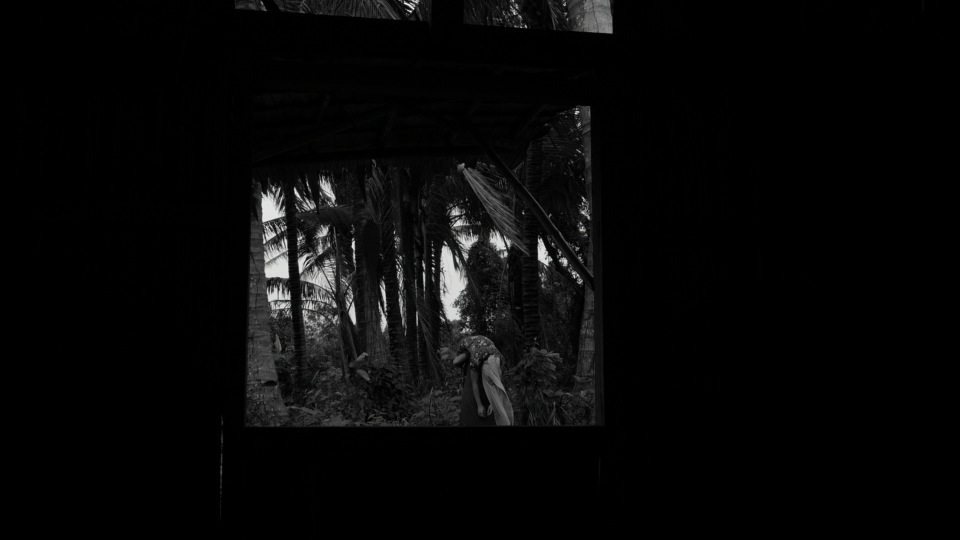

From What Is Before

Dir. Lav Diaz

For the last couple years, the name Lav Diaz has been thrown around more and more as one of the new great arthouse directors. His marathon-length films, usually ranging from 4 to 10 hours, have become something of a legend, in part because they’re allegedly pretty great and in part because the recent retirement of Hungarian master Béla Tarr left the film world one man short on the slow-burning cinema-of-time team. I won’t lie and say the five-and-a-half hour length wasn’t intimidating, especially after learning there were no intermissions (Tarr’s seven-and-a-half hour magnum opus, Satantango, mercifully offers two breaks at about the 1/3 and 2/3 mark), but I’m also aware that even in a major film city like Los Angeles, the chance to see Diaz’s work in a theater are few and far between. The film does take a while to get into, with the 90 minutes mostly devoted to observing the daily routines and rituals of the small Pilipino town where the film takes place. Slowly, Diaz allows the characters and the context of the film to come to the surface — set in the 1970s and based on his memories of the events, because after all what story is wholly true, several cows and one man are mysteriously murdered, and the military eventually come and declare martial law. From What Is Before’s epic length allows this transformation from a struggling but functional pastoral town to a near-deserted wasteland to achieve grandiose tragic heights fully grounded in temporal and spatial realism. It’s a challenging film, but it rewards with a fully realized historical context, multifaceted characterizations, and profound philosophical and political realizations.

Gueros

Dir. Alonso Ruiz Palacios

This was actually a Plan C film that I saw only after plans A and B fell through. My only knowledge of it beforehand was of its comparison to the French New Wave and a trailer that made it look fun and experimental. It is little gems like this, a film that may not get a distribution deal (at least in the U.S., though it does have distribution set in Mexico), that makes taking chances on the smaller, unknown films worthwhile. Gueros marked the impressive debut of a unique new voice in cinema, Alonso Ruiz Palacios. Taking his cues from Fellini and the French New Wave, Palacios created a picturesque road film that is both a visual tour of his home city, Mexico City, and a powerful and amusing story of four aimless, drifting teenagers. The film revolves around 14-year-old prankster Tomas, his brother, and his brother’s friend and girlfriend as they find themselves becoming further involved in a student strike at the city’s university. Eventually they’re left wandering through Mexico City in search of an elusive singer/songwriter who their late father turned them onto and who supposedly once made Bob Dylan cry. Palacios deftly navigates the landscape, seamlessly switching tones, moods and paces, rendering Gueros a film full of rich emotions, raw settings, and a unique portrait of youth in rebellion.

Leviathan

Dir. Andrey Zvyagintsev

Corruption in Russia isn’t exactly a new concept, but the degree to which it’s entrenched into the daily lives of its citizens, even in the smallest, most remote towns isn’t something the West ever hears about. Andrey Zvyagintsev uses the Book of Job as loose model for his modern tale of a man, Nikolai, who lives in a tiny coastal town with his wife and teenage son, fighting the corrupt mayor for the right to keep his house. The mayor has other plans, ironically to build a fancy Orthodox Church for him and his wealthy friends to attend, and when Nikolai gets his friend Dmitri, a powerful lawyer in Moscow, onboard to help him in the fight, the dirty games begin. Leviathan does drag at times, particularly in its hefty middle section, but the powerful symbolism of the gut-punching finale makes it worth the wait, even it makes you lose even more hope in humanity, or at least the portion that resides within the Russian borders.

Mr. Turner

Dir. Mike Leigh

As a rather avid Mike Leigh and Timothy Spall fan, I was excited to see Leigh return to biopic territory (a sub-genre I often loathe, but which the director so brilliantly mastered with Topsy Turvy) and to see Spall’s performance of 19th Century tortured painter, J.M.W. Turner, which garnered him the Best Actor prize at Cannes. Spall is as magnificent as promised, grunting and groaning his way through Turner’s life, exhibiting the man’s emotional and artistic turmoil through mostly wordless sounds and facial contortions. His droll and complex performance of a man who few at the time cared for is the glue that holds this film together, and while this may be Leigh’s most gorgeous-looking film, I will always prefer the grimy, rain-soaked streets of London in Naked. It’s certainly not a bad film, but aside from Spall’s performance and the cinematography, this is one of his lesser works.