Richard Henderson provides a challenge with his love letter to Song Cycle. Rather than questioning the music-buying public of 1968 or dare doing anything to besmirch the pristine mythos of Van Dyke Parks, Henderson instead divides the whole of Song Cycle into two camps. He spends a great portion of the book leading us down a more conventional path by comparing Parks’ solo debut to his comrades, Randy Newman and Ry Cooder. The notion that Parks, despite his penchant for drugs, philosophy, and experimentation, was a part of a more streamlined factory of potential hitmakers is continually reinforced throughout Henderson’s prose. Yet it’s the idea that Parks created a psychedelic masterpiece that lends the latest 33 1/3 exposé a unique slant.

Despite Henderson’s affection toward Song Cycle as outsider art, he keeps the album grounded with continual comparisons to the debuts of Newman and Cooder (Parks was co-producer on both alongside Lenny Waronker), using statistics of sales, advertising, and art direction. He goes so far as to mirror their career trajectories onto Parks, as all three were part of a new Warner Bros. at a time when the music business was in upheaval. But while easy to gloss over, Henderson’s attention to detail also gives birth to the fantastical idea that Song Cycle, as well as the debuts of Cooder and Newman, were not just solid examples of songwriting, but masterworks of innovation.

This is where Henderson’s novel moves from nostalgic ode to doctoral thesis, arguing that Song Cycle is a dusty relic of true psychedelia. It’s a bold argument. Consider what most would classify as the psychedelic sound, and the work of Van Dyke Parks would hardly seem a worthy contender. Yet through the album, Henderson quickly — but powerfully — describes Song Cycle as a far-out chameleon, utilizing tempo and mood changes so abrupt that one cannot help but feel as if they are on a never-ending trip. He explains, convincingly, how Parks disorients with volume and style, relying on bizarre studio tricks and sly distortion to bend sound to his will.

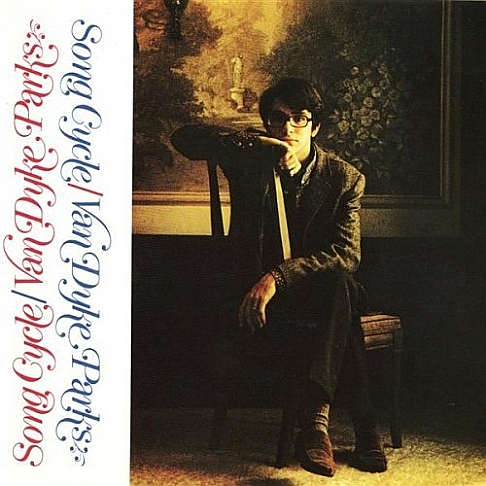

A book so straight in its delivery but so dreamlike in its unconditional love makes the perfect case that psychedelic music is not a sound but an ideology, one that’s in fact at the heart of Song Cycle. As a novel bent on describing the minutia of Song Cycle, few 33 1/3 entries come close to matching Henderson’s clinical tone. But among his tweed jacket lectures and calculus figures, he also creates a fundamental argument about genre. And by prodding the ad campaigns of Warner Bros. and dissecting the album art, he only furthers the idea that “outsider art” like Song Cycle is necessarily counterculture.