David Lynch and Mark Frost's Twin Peaks aired its last episode of season 2 in 1991, over a quarter-century ago. With the series finally making its return for season 3 on Sunday, May 21, we are celebrating all week with a string of Twin Peaks-related features. More from this series

[A Bewick’s wren perches motionlessly on a thin branch.]

In 2017, Twin Peaks is an invigorated brand. It has awoken as if to a new life, walks and breathes more freely. It is viewed on laptops, tablets, phones, and smart televisions connected to Netflix, and it will soon be viewed on SHOWTIME. But how will Twin Peaks be viewed in the year 2117? On what devices? Will it be viewed at all, or will its exact content be experienced in some truncated, more immediate form, facilitated by body-altering technologies yet to be discovered? Who are the people who download Twin Peaks to their brains in the future? Where do they live? These are the kinds of questions SHOWTIME will have to answer in order to ensure the continued relevance of the reawakened, newly optimistic, and hungry Twin Peaks brand.

Maybe those viewer-subjects live in a huddled condition, in what philosopher Peter Sloterdijk calls “ecological stress communes,” pressed inland and away from cultural centers now remembered and revered like ancestors, jostled about by resource scarcity, plagued by ridiculous fantasies of aliens and sea people punctuated by actual disaster, war, and collapse. Or maybe these troubles loom on their horizon. In the face of these real nightmares, do they dream of ending up in a place like Twin Peaks, of grappling with its fake demons? Maybe future Twin Peaks viewers see in it a refreshingly provincial vision of encompassing crisis. A town where a yellow light still means “slow down” resonates abstractly with them. They are absorbed by the dark forces stirred out of the brown-gray American forest, by the murder of the cocaine-addicted homecoming queen and secret prostitute. Maybe, naive to the reality of their own circumstances, they feel like Dale Cooper chasing after those elusive and idealized spirits.

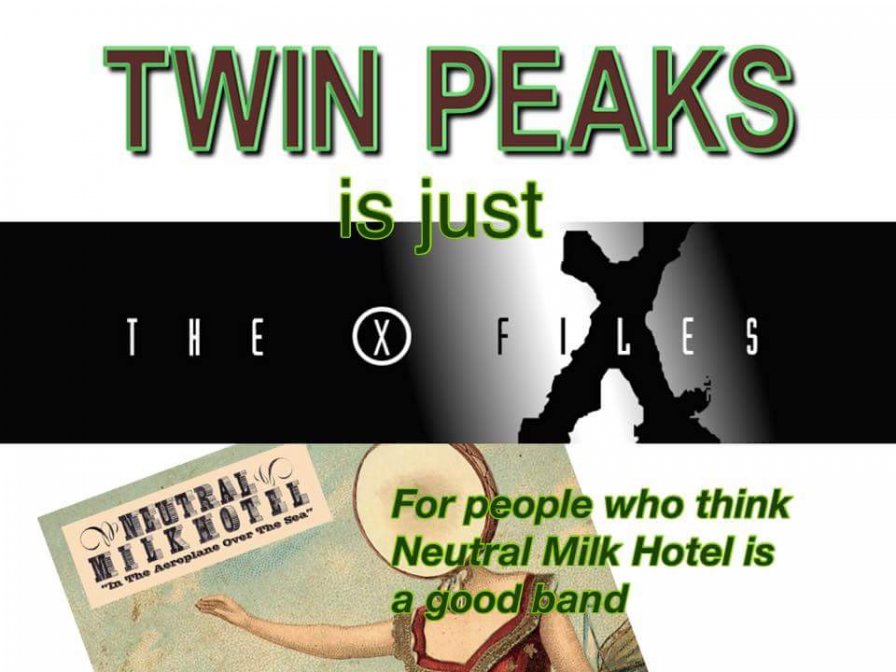

The forces that will carry The X-Files and Twin Peaks together into the cruel future are similar, but not the same. The X-Files, in its simulation of a crackpot investigation motivated less by superstition than clandestine knowledge and bizarre technology, at least has something like a vision of the future, where Twin Peaks only has a vision of the past, and a pretty abstruse one at that. If, disingenuously, The X-Files sought to domesticate the demons split open by modern techniques of investigation, Twin Peaks was overcome by its monsters, disenchanted and reduced to an incomprehensible aesthetic litany. Where The X-Files resolved about a mystery per episode, Twin Peaks lacked satisfying answers. And while we don’t know how Twin Peaks will be viewed in the future, SHOWTIME is wise to bet on disenchantment, on unanswered questioning and the melting of things into dark, muddy pictures.

[Three white plumes ascend from the smokestacks ahead.]

You wake up from an unclear dream in the late afternoon. The year is 2011 or 2012. Your room is dark and warm. Your laptop is next to you, partly covered by sheets. Disoriented, you rub gunk out of your eyes. You were up late browsing Tumblr again. Your laptop screen opens upon your unrefreshed dashboard, where you had fallen asleep to a looping GIF of Laura Palmer’s freeze-framed VHS smile from “Pilot (Northwest Passage).” You “like” the post. Co-created by David Lynch, a pioneer of American avant-garde cinema known for such films as Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive, the show mixes Lynch’s unique brand of surrealism with a dated form of the primetime drama in a way that you’ve enjoyed since you were introduced to the show by friends on the internet. One of the many reasons you love Twin Peaks is that its characters feel like people you know in real life, even though everything else in the show feels very unfamiliar. Twin Peaks makes you nostalgic for a time you don’t remember and a place that doesn’t exist.

Before you knew who David Lynch was, you had seen Laura Palmer wrapped in plastic, an icon of ossified innocence. It would take Lynch and Mark Frost a while to notice, or to do anything about, the fact that Twin Peaks had taken about 20 years to strike the nerve it was always supposed to hit, the one in you. Maybe they were too cynical, too forward-thinking. They thought your parents would be like this. Or, more likely, the conversation they staged between the avant-garde and its supposed opposite traumatically fell through, revealing, eventually, the uncanny mixture obscured by those labels, which they never knew how to control. It took a while to work itself out.

By eventually thickening the show with supernatural diversions and visually peculiar dream sequences, ultimately leaving many of its mysteries unsolved, Lynch and Frost created the perpetual conditions for a scrupulous, even paranoid viewing of Twin Peaks. The question is how the show’s visual language, founded upon a mostly-arbitrary complexity inherited equally from Lynch’s experimentalism and from the genre within which it is put to work, means anything at all after the fact of its disenchantment — aestheticized, separated from the ostensible movement toward resolution. Or, as Anamanaguchi’s Peter Berkman put it in a reply to a comment on one of his Facebook status updates, “the question is how that grammar has changed now that we can pause and dissect individual frames in and out of context.”

You close your eyes, take a deep breath, and keep scrolling Tumblr.

[Sparks fly from the grinding wheel as you move in for a closer look.]

INT. GREAT NORTHERN HOTEL DINING AREA - MORNING

Sunlight pours into the room from the right. DALE COOPER sips coffee, his tape recorder placed neatly in front of him on the table.

COOPER

Diane, the time is 8:05 A.M., I’m at the Great Northern Hotel. I’ve just awoke from a terrible and convoluted dream. I’m not sure how much of it was significant to the inquiry into Laura Palmer’s death and how much of it was fabricated by BOB for the purpose of diverting it; to be honest, I’m not even sure if BOB or the Black Lodge are real anymore. I don’t know if I care or if the outcome of the investigation is important to me. I feel terrible. I lied awake in bed for a few hours. I feel like I’m living in someone else’s bizarre fantasy. (He pauses.) I mean, I guess her dad did it? I live at this hotel now.

BOBBY BRIGGS enters from the GREAT NORTHERN HOTEL LOBBY holding a football.

BOBBY

Hey, Coop! Catch!

BOBBY throws COOPER the football. COOPER fails to catch the football and it hits his tape recorder, sending it flying into the mug of coffee.

COOPER

B-Bobby! I —

AUDREY HORNE enters from the GREAT NORTHERN HOTEL LOBBY smoking a cigarette, holding an iPhone.

AUDREY

(puffing cigarette)

“When the masses think, the intellectual dies.”

–Antonio Negri

[A massive log looms atop a dolly.]

Was Twin Peaks an attempt to make the masses think, to think with the masses and to kill the intellectual, or to think of the masses? To create an intellectual picture of their supposed fears and superstitions, their vices and neuroses? First, there’s Cooper and his obsession with an idea of homespun authenticity, one of the show’s biggest memes. There’s also Harry S. Truman, the sheriff, well-intentioned and pragmatic; Bobby Briggs, the football star, surly and unpredictable; the show’s various tokens of the bumbling serendipity of small-town America (Andy the cop, Pete the loyal husband); and the town’s enigmas and obsessives (James the boyishly gilded biker, Leland Palmer, Lawrence the shrink, and Harold the shut-in). Then, there’s a group of female characters, beginning with Laura and growing to include Shelly Johnson, Donna Hayward, Audrey Horne, Norma Jennings, Josie Packard, Lucy Moran, and Catherine Martell, who are depicted at best as seriously or repeatedly traumatized and, at worst, as stupid or possessed by some unknown whim, complicit in their own undoing. Where the town of Twin Peaks is bottomless in its dark mythology, it is flat in other ways.

The image of community in Twin Peaks is convincing, actually, because it is not realistic. It is a vision of the countryside native to the city and is nonetheless awkward in representing both. FBI agents and industrialists, the show’s main representatives of the latter, view the fixed category of “provincial values” with lust or disdain. The working assumption is that the city is a place that mystery and magic have abandoned in favor of particular backwaters. That urban coexistence is antithetical to wonder.

Moby’s “Go,” the popular rave-inspired electronica single based on a sample of Angelo Badalamenti’s theme music for Twin Peaks, is both clearer about who it is talking to and more successful in its attempt to practice an inclusive form of mastery over its created public than the show itself. As I drive east on Phoenix’s Loop 202 away from the setting sun, “Go (Woodtick Mix)” fades into “Go (Soundtrack Mix),” a line of a hundred cars curving delicately to the returning, quantized “yeahs.”

[A waterfall crashes.]

Everybody needs an escape from the avant-garde. To think all of the time is difficult, and it seems better that one find some place of negotiation, where many people think more and few people think less. As an escape strategy, Twin Peaks faltered in its weirdness, its stubborn maintenance of a position among the few. It was, moreover, unrealistic in its concept of the many. Gesturing toward the avant-garde, it failed there most spectacularly; no matter the depth of the perennial ebb and flow of interest in Lynch’s work, it will always make complete sense to me that Fire Walk With Me was booed at Cannes. If Lynch’s murderous backwater is perfectly fitted to the fetishes and anxieties of today’s teenagers, it is only because they have many of the same fetishes and anxieties as their parents, who watched with baited breath until the questions and clues lost their impact. Lynch’s vision of provincial intrigue said more about the values and aesthetics of America’s cities than its towns, and it appeals to we who carry with us everywhere a version of what Lynch saw in the city.

Today, Twin Peaks exists against the backdrop of a nostalgia cult. Millennials, lacking spiritual unity and drawn to promises of darkness, are fascinated. Resuscitated by the esoteric magic of the brandscape, will Twin Peaks really walk and breathe more freely, as if awoken to a new life, and find something like that original sense of purpose? Or will it lose its way again in the smoke and mirrors of a shoddily constructed model of the public?

On this auspicious morning for Twin Peaks, you languish in your room, thinking of the past. Of dead memes, content dampened and wrapped in plastic. Sometimes you wish you could immaterialize, becoming the unfeeling aggregate of your social footprint. You dream of disappearing into a fog of blogwave, street style, spicy memes, or Twin Peaks. Other times, you feel surprisingly up to the task of remaining an aggregate of relations. Your mental image of your environment sometimes appears in the form of a monster you are working to vanquish. With an intoxicated discomfort like nausea, you realize that Laura never lived in a world, had a future. That the real mysteries were yours.

[You approach a wooden sign on the right side of the road.]

David Lynch and Mark Frost's Twin Peaks aired its last episode of season 2 in 1991, over a quarter-century ago. With the series finally making its return for season 3 on Sunday, May 21, we are celebrating all week with a string of Twin Peaks-related features. More from this series