This marks our first mid-year film list, showcasing our favorite movies of 2012 so far. When we first thought up creating this companion piece to our mid-year music list, we were worried about finding enough worthy films. But in the end, this year already has so many films we love that the real difficulty was narrowing it down. The Oregonian, Your Sister’s Sister, The Dictator, Patience (After Sebald), Polisse, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, and The Observers all almost made the cut. Slippery film release dates also kept us from including films from 2011 (or, in the case of World on a Wire, 1973!), that didn’t see wide release until 2012 (Sleeping Beauty), just-released gems (Alps), and festival favorites that are still waiting for theatrical releases (Holy Motors). But enough about the almost-rans. Here’s our list, with new blurbs for two films that we didn’t have reviews for, and one new blurb for a film we initially panned. The rest are snippets from our reviews. While the list begins and ends with two (vastly different) versions of the apocalypse, for film, 2012 is anything but. –Benjamin Pearson

The Turin Horse

The Turin Horse

Dir. Béla Tarr

[Cinema Guild]

“Consisting of nothing more than increasingly apocalyptic yet overwhelmingly mundane days in the life of two destitute peasants, the plot of Béla Tarr’s latest film is about as barebones as it gets, even by his own imposingly glacial standards. Offering precious little in the way of action aside from a daily meal of a single potato, grueling slogs to the well, and the bellicose stasis of their horse, Tarr forces viewers to extract meaning from his formidable aesthetic techniques as a sort of compulsive reaction to the prodigiously overpowering boredom that quickly sets in once the realization is made that little else is going to be offered. Although his films are renowned for trying audiences’ patience through his reliance on extended takes and nearly-static images, The Turin Horse is perhaps the first to make refusing the audience’s desire for stimulation a central element. While Tarr’s seven-and-a-half-hour Sátántangó is leavened by a consistent use of black humor and the attention-piquing intrigues of film noir convention, The Turin Horse offers a plot that offers precious few entertainments outside of its interpretation. This dearth of traditional interest, however, becomes a distinct tool in the hands of Tarr, opening up new ways of viewing and interpreting, even within his body of work. The Turin Horse is dull to the extreme, yes, but its dullness is forced into becoming an asset.” [Full Review]

Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochiez!

Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochiez!

Dir. Everything is Terrible

[Self-Released]

“While the dogstravaganzas Marley & Me, Bolt, and Beverly Hills Chihuahua were all in Hollywood’s top-grossing films of 2008 (an exceptional vintage for the industry, obvs), nothing should feel timely about an adaptation of a 1970s cult film made out of 1990s videos about dogs. But Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochiez! couldn’t be more zeitgeisty in its digital decimation and recreation of the analog. The film’s total subjugation of seemingly all the dog-themed output of an entire medium (VHS) mirrors modernity’s total digitization of cultural artifacts into MP3s, Hulu streams, and Kindle downloads. But by training VHS dogs to emulate celluloid — the ancestral medium of the filmic — Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochies! diagrams analog-to-digital not as progress, but perhaps more accurately: as an endless feedback loop. That loop, as the film’s final scene (which one-ups the meta of The Holy Mountain’s fourth-wall breaking finale) illustrates, can be all-encompassing. Shit jokes and spirituality are the same meme.” [Full Review]

The Kid With a Bike

The Kid With a Bike

Dir. Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

[Sundance Selects]

“The Dardennes are fanatically straightforward throughout the film — there is no complicated storytelling, and their characters simply say what they mean. In many ways, the film is simply an analytical study of growing up, a bildungsroman delivered in five neat little chapters, each with the same orchestral flourish (the film’s only non-diegetic sound) signaling its close. Despite this artifice, however, they’ve managed to construct an honest, powerful examination of adolescence at its most vulnerable. [The film’s protagonist] Cyril is frightened and friendless, and watching him approach his peers is fascinating. He falls in with troublemakers, but [actor] Doret does a shockingly masterful job of showcasing the moral battle within Cyril as he drifts between his guilt and the inevitable lure of community. The neatest analog for Cyril is Truffaut’s youngest version of Antoine Doinel. But where Truffaut wanted rebellion, the Dardennes want only comfort and healthy growth for their troubled lad. […] With The Kid With a Bike, the Dardenne brothers have delivered an elegant film, one about a child’s first encounters with both abandonment and acceptance, a story of trust lost and regained. They have wrung flawless performances from both their stars and have managed to tell their story within the microcosm of a simple Belgian village. Watching Cyril shift from little terror to promising youth is eminently joyful. Cyril’s adventures are simple, powerful, and moving.” [Full Review]

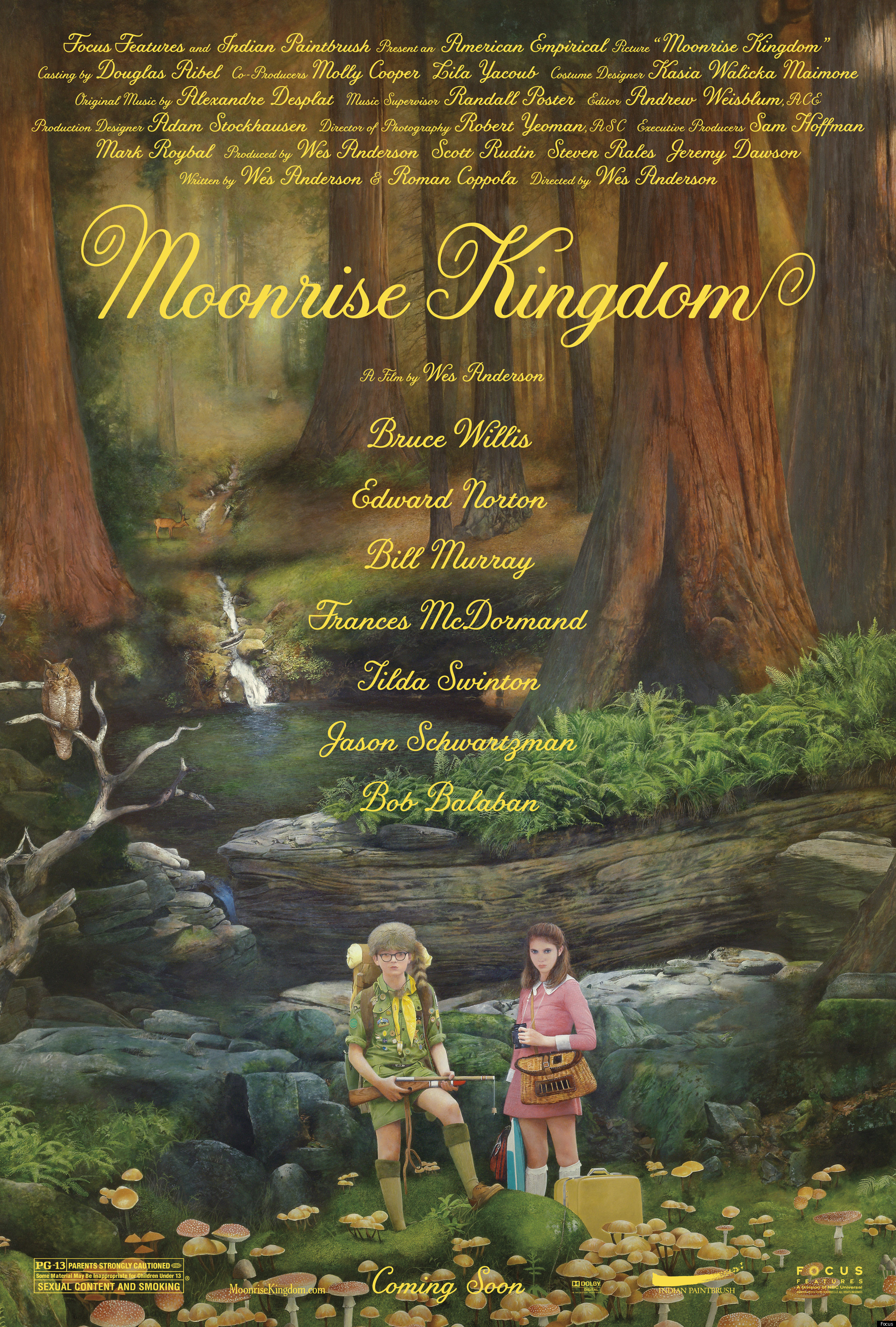

Moonrise Kingdom

Moonrise Kingdom

Dir. Wes Anderson

[Focus Features]

In Moonrise Kingdom, Wes Anderson plunges the audience into a world of mannered quirkiness, and the film’s detractors (including us, in our review) may roll their eyes at the familiar style. The opening credits look hand-written, the camera pans left or right with unwavering steadiness, and the clothes are bespoke. But the repeated tropes are hardly a crutch for Anderson: Moonrise Kingdom is his most focused work yet. Still, the best thing about it is how it never condescends to children, whether in the audience or onscreen. It can be funny when a group of preteens hatch escape plans or prepare for battle, but what matters is how they never seem like they’re in on the joke. As with Fantastic Mr. Fox, the director seems to understand children better than they understand themselves. Precocious kids will see themselves as they watch Moonrise Kingdom; older audiences will remember what it was like to feel like them. It’s a strange miracle how Anderson evokes our most awkward years and has us laugh, not cringe.

A Separation

A Separation

Dir. Asghar Farhadi

[Sony Pictures Classics]

Iranian director Asghar Farhadi has called his Best Foreign Language Film Oscar winner A Separation a “detective movie where the audience is the detective.” While you can see where he’s coming from, it’s a hopelessly ineffective way to describe his latest. Maybe it’s simply the film’s piercing emotional directness that prompted so deceptively prosaic a description. A Separation revolves around a death, a divorce proceeding, and the reconstruction of a mysterious incident, but nowhere does it ask the audience to act the part of a rumpled J.J. Gittes-type sleuth — there’s no digging though some wealthy family’s dirty laundry here. Moving in long, emotionally-draining scenes where quiet talk leads inexorably to violent screams before settling into stilted regret, Farhadi watches his actors suffer through these vicissitudes with handheld camerawork that never shies away from their faces. This stylistic and emotional directness serves as ballast to the circuitous unfolding of the story and the audience’s constantly-shifting epistemology. It’s a film of awesome performances and gnawing emotional baggage.

Michael

Michael

Dir. Markus Schleinzer

[Strand Releasing]

Austrian Markus Schleinzer’s directorial debut follows five months in the life of a titular pedophile who keeps a 10-year-old boy locked in the basement of his suburban home, but it’s not the film’s implied sexual brutality that unnerves so much as its richly rendered approximations of domesticity. An argument over a dinner of pan-fried meat, an evening decorating a Christmas tree, hours assembling a jigsaw puzzle, the child-friendly décor of the tightly-locked bunker — under Schleinzer’s clinically precise lens, the mundanity of these nearly-normal details occupies the places usually reserved for the judgment of the deviance from which they’ve sprung. Pedophilia defines Michael, but only because without it he’s entirely unremarkable, too realistically dull to even be a caricature. Incredibly, though, it never defines the film. Schleinzer’s created one of cinema’s most nuanced, complex portraits of a child molester, but in doing so, he’s dispassionately unraveled the very taboo he started with. What’s left is both more familiar and more chilling: relationships, family.

Your brother. Remember?

Your brother. Remember?

Dir. Zachary Oberzan

[Self-Released]

“In his latest ultra-low-budget feature, Zachary Oberzan has undertaken a sort of microcosmic and deeply personal Up series examining brotherhood, memory, time, and loss — as well as both the cultural significance of Jean Claude Van Damme’s riveting performance in Kickboxer and the 1978 cult classic trashfest Faces of Death. Originally a mixed-media theater piece, Your brother. Remember? is a film that’s been 20 years in the making. It’s also one of the greatest uses of a medium to parse both itself and its maker that I’m aware of. Blending joyous humor with weary regret and contrasting hilariously ludicrous action with crushing emotional paralysis, Oberzan has created something genuinely sui generis and thoroughly entertaining. Once again, this fearless director has transcended monetary and technical limitations to rouse his audience.” [Full Review]

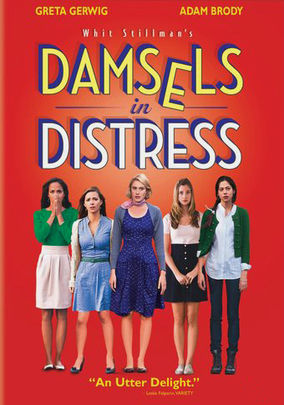

Damsels in Distress

Damsels in Distress

Dir. Whit Stillman

[Sony Pictures Classics]

”[Damsels in Distress] plays at the top of its intelligence, rarely pausing long enough to let the audience reckon with whether or not they’re being condescended to, winked at, lauded, or mocked. This is what seems to undo Stillman in many viewers’ eyes. His films beg you to look around the theater, making sure everyone else is in on the joke. There’s nothing fresh in pointing out Stillman’s fixation on privilege and its soignée discontents, but one can’t help but notice that this director deals primarily with the non-problems of the finishing school set and always seems to come down on their side in debates. In an era when people are willing to affix a tag of ‘white people problems’ to every act unwilling or unable to mask its privilege, Stillman remains defiantly forthright about his origins and his concerns. Whether this makes him brave, an ass, or both is a decision best left to the individual ticketholder. Damsels, thankfully, spares us somewhat from that argument by being so funny that it’s impossible to take any side seriously — all that’s left to smirk at is the folly of youth.” [Full Review]

The Color Wheel

The Color Wheel

Dir. Alex Ross Perry

[Cinema Conservancy]

“Taking the 1970s self-discovery-via-road-trip model as his starting point, director Alex Ross Perry sketches a dirt-simple narrative concerning a non-starter of a writer (Alex Ross Perry) helping his aspiring TV journalist sister (Carlan Altman, who also co-wrote the script) out of her ex’s apartment. In classic mumblecore tradition, each are consumed with the most prosaic of relationship problems, and the bulk of the action consists of a series of bitterly awkward encounters conveyed through dialogue that careens from comedic to deeply pathetic, often at the same time. For the majority of the running time, Perry is content to define his characters through their jobs and their tics, with no sign of any inner depth worth speaking of. But at long last comes the film’s vicious kicker of a final twist, and the non-details of the bulk of the film are suddenly reworked into a psycho-dramatic shocker that renders The Color Wheel deeply reminiscent of 70s chamber pieces, both shockingly gonzo and shockingly coherent.” [Full Review]

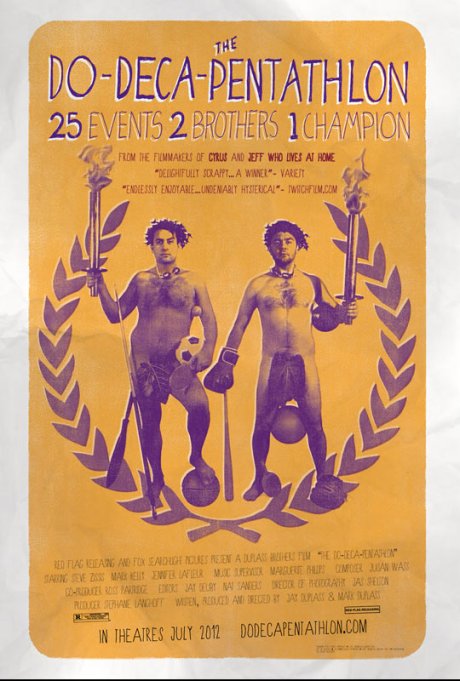

The Do-Deca-Pentathlon

The Do-Deca-Pentathlon

Dir. Jay and Mark Duplass

[Red Flag Releasing]

“With their fifth feature in eight years, you could say the Duplass brothers have come full circle, or you could say they haven’t moved an inch. After widening their scope with household names in Cyrus and this year’s Jeff, Who Lives at Home, we now find them reining it in and returning to their roots. While they never strayed too far from their origins, The Do-Deca-Pentathlon’s modesty is essentially the antithesis of Jeff’s cosmic grandeur. It’s an exercise in simplicity and a brief note to an old friend. It’s also their slightest film to date, and that’s quite an accomplishment for such avowed minimalists. The sliver of Do-Deca’s plot can be boiled down to a timeless archetype: two brothers and one thing. It’s biblical and Duplassian, and while they’ve mined this trope before, they will almost inevitably come back to it in the future. In this case, the siblings are Mark (Steve Zissis) and Jeremy (Mark Kelly), both approaching middle-age with radically different lifestyles and opposing personalities. Mark is depressed, irascible, flabby, and married to the joy-killing Stephanie (Jennifer Lafleur), while Jeremy is a professional poker player, strip club regular, and complete asshole. Their relationship is wrought with deep-seated tension dating back to when they were kids competing in an Olympiad of their own design called the Do-Deca-Pentathlon — an amalgam of 25 grueling events and feats of strength testing their endurance, dexterity, and quickness in a laser tag arena.” [Full Review]

Oslo, August 31st

Oslo, August 31st

Dir. Joachim Trier

[Strand Releasing]

“After using him to such great effect in Reprise, Trier has again found in actor Anders Danielsen Lie the perfect vessel for his message. A doctor in his non-acting life, Lie perfectly translates what Anders the character is unable to: that there is no way to describe a life that would satisfy him, despite having every opportunity to be satisfied. What drugs and partying offer Anders are an opportunity to escape not only those he’s disappointed — his family, friends, an old girlfriend he can’t stop calling — but also an opportunity to forget the baseline melancholy that can come with simply being alive. It’s the same angst David Foster Wallace and a battalion of other artists went to war with, and like them, Trier offers hope where his character can’t. The film’s overture consists of a series of home movies, images of the city with voiceover from various unknown characters describing their youth and how they came to know Oslo. The stories emphasize connection; they’re sentimental, unremarkable, and quietly joyful, a subtle repudiation of solipsism. The film closes with another series of images, many very similar to the first: places we know Anders briefly occupied, now accompanied only by silence.” [Full Review]

Prometheus

Prometheus

Dir. Ridley Scott

[20th Century Fox]

“On paper, director Ridley Scott’s new film Prometheus, in which a team of scientists discovers that life on Earth was designed by aliens, is about our search for what gives human life meaning. But like last year’s Tree of Life (TMT Review), another grandiose attempt to cinematize our distant origins to which Scott’s latest has been compared, Prometheus is more interesting for what it reveals about our relationship with film than with otherworldly realms, whether Godly or extraterrestrial. Both films trace humankind’s lineage back to its point of origin, and, unsurprisingly given this pre- (and post-) human scope, place more emphasis on visual spectacle than their disjointed narratives. But with near ubiquitous complaints about its supposed plot holes, lack of character development, failure to definitively explain the themes it hints at, and attention to visuals above all else, Prometheus’ divisive reception is its biggest similarity to Tree of Life. In Scott’s new film, the epic search for meaning its characters embark upon as they travel to meet their makers is punishingly cruel and depressingly empty, likely mirroring many a literally-minded viewer’s attempt to decode film itself. But nobody ever went to the movies to figure it all out: both filmically and not, Prometheus is dazzling in its agnosticism.” [Full Review]

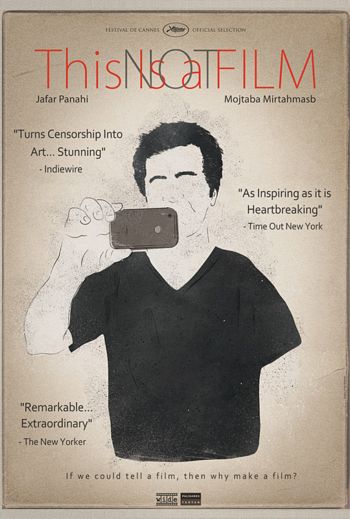

This Is Not a Film

This Is Not a Film

Dir. Jafar Panahi

[Palisades Tartan]

“Iranian director Jafar Panahi was sentenced to six years in prison and banned from filmmaking for 20 years in December 2010 for political reasons. He can’t leave the country and he can’t work; he can only wait in his (admittedly luxurious) apartment for the final verdict pending appeal. This Is Not a Film begins with a shot of Panahi eating breakfast and calling who turns out to be the documentary filmmaker Mojitaba Mirtahmasb to tell him to come over and hear some ideas for a film. Panahi gets dressed, listens to a voicemail message from his wife, and calls his attorney about his case (no hope of reversal in a political case like his, only of a commuted penalty). He talks to the camera about films and about film proposals the government denied. Then Panahi stages a telling of his latest completed script, about a girl whose parents have locked her in the house alone to prevent her from enrolling at the university to study arts. Panahi’s performance is powerful in the context of apparent futility (a futility continuously undermined and exploited by the not-performance and not-film). Panahi breaks down; after composing himself (wink wink), he says something like, ‘If we could simply tell films, why would we bother to make them?’” [Full Review]

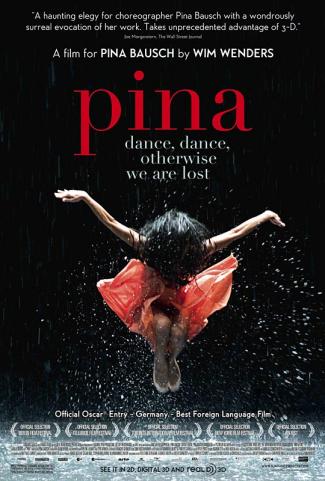

Pina

Pina

Dir. Wim Wenders

[Sundance Selects]

“Wim Wenders has never attempted to hide his abiding fascination with music and dance. […] It’s no wonder, then, that Wenders took up with legendary choreographer Pina Bausch and her group of famously inventive dancers at Tanztheater Wuppertal recently to create one of the most definitive movies about dance ever made. Although, it almost didn’t happen: Pina Bausch died of cancer two days before principal photogrpahy got underway. Named in honor of Ms. Bausch, Pina began as a profile on her career (as both a choreographer and a dancer) and a celebration of her craft with the artists she’d kept close to her throughout the years. Naturally, Wenders and the Tanztheater Wuppertal principals had to drastically adjust course when tragedy struck and they realized the subject of their film would not be able to join them. Broken up into segments featuring inventive stagings of a selection of Pina’s most well-regarded pieces and short snippets of interviews from Pina and her dancers, the film (mainly through the astounding work of the dancers it follows) creates a sense of escape that doesn’t break from start to finish. The interviews themselves are paced in such a way as to maintain a continuity between dances, and the way Wenders chooses to film these visceral numbers is anything but static; it is to his credit that we are allowed such an intimate experience of Pina’s works.” [Full Review]

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Dir. Benh Zeitlin

[Fox Searchlight]

“A sprawling, folksy epic with a big heart, Beasts of the Southern Wild is the remarkable debut feature from director Benh Zeitlin and the Court 13 filmmaking collective. This densely layered film is a fable about grief, told through the wondrous gaze of a young girl named Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis). She and her father Wink (Dwight Henry) live in a harsh Eden, a remote bayou of southern Louisiana called the Bathtub, that they cling to with hardscrabble devotion. These names tip you off to the fact that we are still on the grid, but only barely, hanging onto reality — and America — by a wisp of land that threatens to sink into the sea. This is the margin, a border landscape of swelling waves and gristly animal bones, where every creature fights for survival, and Hushpuppy is no different. She has an innate, mystical sense of this, lifting animals to her ear to listen to their heartbeats; her language describes a universe getting ‘broken’ or ‘busted.’ Her fears are realized — and the delicate balance of her ecosystem threatened — by the arrival of a Biblical storm that will flood the Bathtub. One of the marvels of the film is how Zeitlin doesn’t allow the Hurricane Katrina metaphor to overwhelm the story, twinning the natural apocalypse with a personal one: Hushpuppy’s father is dying. In what Wink knows are his final days, he subjects Hushpuppy to a tough, cruel love intended to prepare her for survival on her own. Beasts of the Southern Wild is a story of how such love and survival twist and turn on each other, an American fable that celebrates one girl’s wild spirit while mourning an irrevocable loss.” [Full Review]

[Image: K.E.T.]